BY Helaina N. Hovitz

On September 11th, 2001, homeless men taking refuge at the NYC Rescue Mission became first responders, handing out food and other supplies to hundreds of dust-covered workers streaming uptown. They lead throngs of men and women in tailored suits to shelter and gave them food, and even a hot shower.

Nine years later, the mission, located at 90 Lafayette Street, is calling on the community for help, as its need for additional space grows more pressing by the day.

The mission began planning a major expansion project in 1999, but in 2001 had to put it on the back burner. Then in 2008 they received a gift of six million dollars from an estate. A year later, John Heuss House at 42 Beaver Street closed its doors for good, and the NYC Rescue Mission saw a 20 percent increase in people looking for food, clothing, and shelter. That number increased another 10 percent this year. Currently the shelter is forced to refer at least 20 people to other shelters every night; it expects to have to turn even more men away once winter sets in and the temperatures drop.

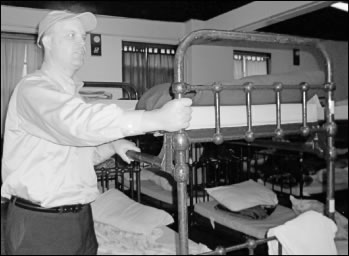

Tom Hall, director of operations, said the mission is about halfway to reaching their goal of $11 million, the projected construction cost of adding three floors and 180 beds, expanding the capacity of the chapel, and acquiring 75 emergency sleep mats.

The mission also wants to launch a pilot program for women that would mean adding roughly a dozen emergency beds.

The mission is not applying for federal funding due to the stipulations and constraints placed on religious-nonprofits, guidelines that would limit the mission’s ability to provide services. According to Executive Director Jim VarnHagen, because they teach a Christian doctrine, they must seek private funds rather than public ones.

“Many funds don’t allow you to conduct religious services, even though organizations that hold religious services are statistically proven to be the most effective,” said VarnHagen.

The campaign is currently relying on individual gifts to raise the rest of the funds needed.

Hall said the city once encouraged homeless New Yorkers to visit drop-in centers during the day and refer people to churches and shelters at night. Now, he said the city’s focus has moved from drop-in centers to a housing-first philosophy where service providers would be charged with finding permanent housing for their clients.

“The city has cut their budget and changed its strategy,” said Hall. “This puts an enormous amount of pressure on us now. We need to increase in size.”

The mission’s staff tries its best to prevent lines from forming outside by keeping their chapel open to the public until the mission doors open at 3 p.m.

“We try to be good neighbors,” said Joe Little, community relations manager. “Nobody wants a long line of homeless people outside, especially with the NYU dorms around the corner.”

The mission serves an average of four hundred people each day, and unlike most men’s recovery missions, it doubles as a drop-in center for women and children. Anybody can eat, obtain clothes, or take a shower at the mission, but the beds are reserved for men only. Twenty-five beds are reserved for the men in the mission’s twelve-step recovery program, which includes educational and vocational classes as well as spiritual counseling.

Men who are willing to make a one-year commitment to the program are assisted in their job search when they graduate, and given the skills they need to start and maintain a new life.

If the mission can raise enough money to follow through with its expansion plan, it will be able to give more men the opportunity to get their lives back on track and become self-sufficient. Last year, fifteen men graduated from the program, up from an average of ten in previous years.

“We used to have to reach out to get enough people in the program,” explained VarnHagen. “Now there’s a waiting list for men who want to join, and new candidates every day.”

Everyone from school teacher to stock broker appear on that list, men who’ve slept in cars and storage closets since their companies went broke.

“Nobody has chosen to become homeless,” said VarnHagen. “But everyone is worthy of being rescued.”