BY WINNIE McCROY | The “Summer of Hell” may not have materialized as predicted — but a July report released by New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer puts the underground commuter’s day-to-day frustrations into sobering perspective.

“The Human Cost of Subway Delays: A Survey of New York City Riders” takes a look at the victims of these delays: among them, the city’s most vulnerable populations, including children, the elderly, and low-income workers.

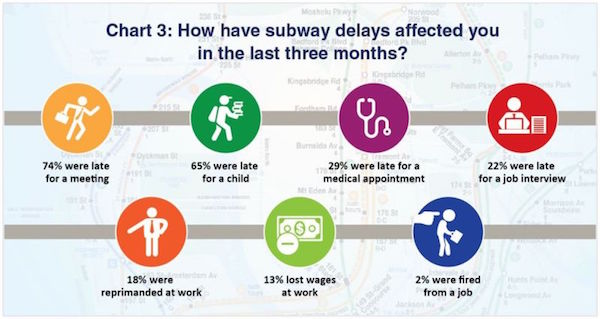

“We surveyed 1,200 riders at 143 stations and found that in the prior three months, 74 percent were late to work, 65 percent were late to pick up their child, and 29 percent were late for doctor’s appointments,” said Comptroller Stringer’s director of strategic operations, Jessica Silver, during the July 26 full board meeting of Community Board 4 (CB4).

“What’s more, 71 percent were impacted by delays at least half the time they rode,” she continued. “The impact of this was very high on low-income communities, who were often reprimanded at work for being late. And it’s worse off in the Bronx, where 54 percent report being late to work more than half the time.”

The subway carries millions of riders each day to work, school, appointments, and other activities. But the aging infrastructure and increasing ridership has taken its toll, resulting in crowded platforms and delayed trains.

The Comptroller’s office wanted to find out exactly who was being impacted by these delays, so from June 13–26, they conducted a citywide survey of riders from 143 stations on every line at morning and evening rush hour, talking to 1,227 riders from 158 zip codes. Regardless of borough, the answers were similar: riders gave the MTA service a “C” or lower, with one of seven giving the subway a failing grade.

Subway delays affect us all, with more than 70 percent of respondents reporting “significant delays” at least half the time they use public transit. But some pay a higher price: delays caused 74 percent to be late to a work meeting, 18 percent to be reprimanded, and 13 percent to lose wages. Two percent admitted they were fired due to MTA delays preventing them from getting to work on time.

“Our subways are in crisis. That’s clear as day. But policymakers have to remember that behind every delayed train and budget fight are real New Yorkers with somewhere to go,” Stringer told Chelsea Now in an email. “From a worker in the Bronx losing out on wages she needs to put food on the table, to a father in Manhattan late picking his daughter up from school, to a senior citizen in Queens who misses a doctor’s appointment, this situation is simply untenable.”

Late trains don’t just affect workers: they also have an impact on those trying to get to a doctor’s appointment, or pick up their kids from childcare. In fact, MTA delays caused 65 percent of respondents to be late for a pick-up, drop-off or child’s function, which can result in late fees or penalties. In addition, 29 percent of those surveyed said delays caused them to be late for a medical appointment.

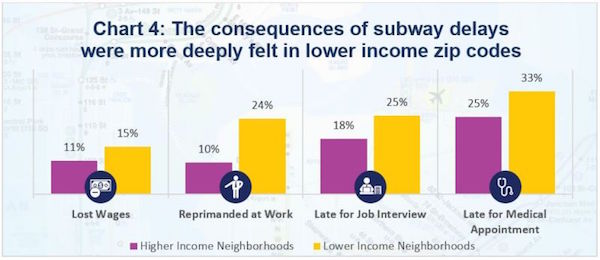

And the consequences hit hard among New York City’s poorest. Among the city’s lower-income zip codes (under $62,150 for a three-person household), 14 percent were more likely to be reprimanded by their boss for being late, and four percent were more likely to have lost wages. Seven percent were more likely to be late for a job interview, ruining their chances to make a good first impression and gain employment.

At the July 26 CB4 meeting, Assemblymember Richard Gottfried said, “The MTA’s chronic delays are a real problem all New Yorkers, but none more so than the economically disadvantaged, who have few other options for trips to and from work or school, to medical appointments, and other necessary travel.”

These riders were more likely to experience significant delays, and thus more likely to give the MTA a “D” or “F” for their service. More than half of Bronx riders reported significant delays more than half of the time, with 68 percent of them giving the MTA a failing grade, as opposed to 21 percent of Manhattan residents giving the MTA a “D” or “F.”

In Manhattan neighborhoods like Chelsea and Hell’s Kitchen, affected riders were more likely than other borough residents to just take a taxi (61 percent vs. 47 percent), but were much less likely to take a bus.

And while the majority of people said they were happy about the MTA’s efforts to improve communication with riders, when it came to on-train announcements about delays or alternative routes, most people just couldn’t hear them well enough to find them useful.

The facts are in, showing the MTA has gone from being on-time 84 percent of the time in 2012 to only hitting that mark 63 percent of the time this year. On-time performance fell by over 31 percent on seven subway lines, with the J/Z winning the prize for latest train, with the C train a close second.

“The MTA has been severely underfunded from keeping the existing system running,” Gottfried said at the CB4 meeting. “We paid for three new subway stations in the wealthiest neighborhood on the planet [the Second Avenue subway line] but the governor is saying it’s all de Blasio’s fault because the city is not paying its share. But the city is putting more money into the MTA Capital Plan than we have in decades, and at the same time the state is regularly pulling money out of this budget.”

Calling the impact on New York City unfair, Gottfried added, “No one asks the people of Nassau or Suffolk Country to put up a nickel for the LIRR track expansion; the only ones who are asked to put money in is New York City. But it’s the State’s responsibility right there in black and white. The State doesn’t ask any other local government to contribute to the MTA.”

Gottfried pointedly noted, in an email statement to Chelsea Now, “The State took responsibility for the MTA decades ago, but it’s been underfunding and defunding New York City’s critically important mass transit. We’ve got to turn that around.”

Stringer’s statement echoed this sentiment, saying, “This challenge didn’t start overnight, and we won’t fix it overnight. But we have to come together — City and State — as one New York, and get to work. That’s why I’m calling for a lockbox that will ensure funding goes where it matters: to getting the subways, and New Yorkers, back on track.”

To download the report, visit comptroller.nyc.gov.