By Ed Gold

A friend who likes to tweak me said recently: “You write some warm and endearing articles about Protestants and Catholics but you never write anything amusing or heart-warming about your own Jewish experience.”

“Well, I wrote about anti-Semitism,” I replied.

“But that was grim,” My friend continued. “How about lightening up a little?”

So I said I’d try.

During my cub reporter days in New Mexico I used to eat almost daily at a popular Greek-owned restaurant on famed Highway 66 that drew many tourists. On cool mornings I usually wore a plaid cowboy shirt and a worn-out leather jacket, but my distinctive feature was long dark hair that approached my shoulders.

One morning a middle-aged couple took seats at the counter near me and became engaged in a hot discussion. Finally, the man came over and tapped me on the shoulder. “Excuse me,” he said gently, “I wonder if you could settle a small argument between me and my wife. Are you a Jewish boy or a Navajo?”

I wanted to keep peace in the family. “A little of one and a little of the other,” I replied.

At the same counter one evening, after I’d been in town for about a year, a stranger took a seat next to me. He eyed me and finally said: “I don’t mean to disturb you but I’m new in town. I just came down from Chicago. I graduated from the University of Chicago and I majored in literature and I’m starting here as a high school teacher in English and drama.” He caught his breath and went on: “My name is Irving Halperin.”

“Oh,” I said with a smile, “you’re a ‘landsman,’” meaning member of the same tribe. Halperin seemed shocked. He leaned over and whispered: “How could you tell?”

In the same town, I made friends with Nick and Dolores, he a high school science teacher and she the secretary at our newspaper. They weren’t Jewish but had friends in the Midwest who were. Some months before Passover, Dolores decided to have a seder in her house, and her Jewish friends sent down a large carton containing all the foods appropriate for the occasion and symbolic of the Jewish exodus from Egypt, which is the Passover story. Included were shank bones, roasted eggs, bitter herbs, the nut/apple/wine mix called haroses and of course plenty of matzo.

My editor, Joe, and his wife, Trudy, were invited. Trudy was a fabulous baker and wanted to contribute to the festivities. She brought a brown bag, which we opened. We found a dozen bagels. As delicately as possible, the hostess pointed out that bagels didn’t really fit into the Passover story.

Since I was the only Jew at that seder I was elected to read the entire Haggadah, which tells the story of the exodus. When I had finished, Joe, who was a hearty Irish Catholic, said: “You Jews are pretty smart. You’ve taken all of our prayers and just dropped the ‘Hail Marys.’” I reminded him who came first.

I had been on the paper for more than two years when a delegation of local leaders approached my desk and placed a check of $1,000 on it. I was shocked to say the least. Then one of them spoke up: “This is down payment on a Jewish church and we want you to be chairman of the fundraising committee. Every other religious group has a church here so we figured it was time for the Jews to have a place too.” It was not what I had in mind in becoming a reporter in this small western town and I was at a loss for words.

On the desk opposite mine, Joe, my editor, was writing away furiously. Finally, he spoke up and came to my rescue. “You can’t have a place for Jews to pray here at this time. The Jews require 10 male adults [age 13 and over] for a service — called a ‘minyan’ — and I count only eight in the county.”

He broke down the list to convince the delegation: “There’s Danoff, the Indian trader, and his two grown sons; the shoe store owner, the manager of the army depot, the beer salesman, the English teacher — and of course Ed.”

Satisfied with the explanation, the visitors picked up their check, but with a parting message for my editor: When two more qualified Jews move into the county, please let them know. After they had gone, I told Joe to give me two week’s notice when he hit 10 so I could leave town. It never happened.

Shortly before I was to leave town for good and head back east, I decided to celebrate Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. I took the day off, had a haircut, put on a clean white shirt, tie and jacket and walked around town. When people asked what I was doing, I said I was celebrating a Jewish holiday.

Over the next few days I received a surprising amount of mail, all relating to my holiday walk. They all wished me a “happy bar mitzvah.”

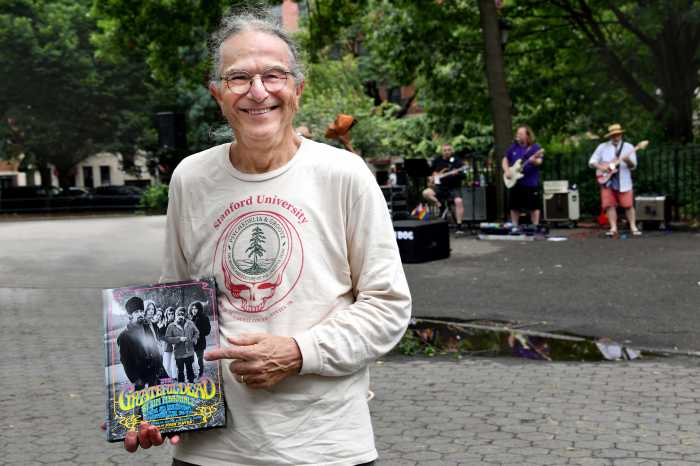

In New York, the Lubavitchers are always after me. I try to be polite but no thanks. They park their vehicle, a “mitzvah tank,” on Waverly Pl. and invariably spot me in Washington Sq. Park. One Sunday, they walked towards me from the arch, so I began moving towards the south side of the park. But heading from W. Fourth was another group of proselytizers — Jews for Jesus. I beat a hasty retreat to the east and watched as the two groups of true believers headed towards one another. They were like two ships passing in the night.

I had a few challenging moments in connection with my marriage. I was married at a friend’s house so the rabbi had to bring a portable huppa or canopy for the ceremony. The canopy had to be held up by four able-bodied persons.

Unfortunately, one of the designated holders had imbibed wine in excessive quantities and was not too stable. In fact, he swayed back and forth while the rabbi was doing his thing, and the canopy repeatedly hit the rabbi on the head. Ordinarily, I would have been upset but, to be honest, I was numb through the entire event.

My best man was able-bodied and sober, but forgetful. He had a memory lapse at the wrong time and couldn’t quickly locate the ring. For a brief moment he forgot he was holding the canopy, but recovered in time to spare the rabbi further distractions.

The other challenge took place a few weeks before the marriage, at an engagement party given by the family. My intended and I had already chosen a rabbi who suited us temperamentally. He happened to be a reform rabbi.

At the party, my grandfather, who was very orthodox, approached. I knew he considered a reform rabbi a “goy,” or gentile.

“So,” he asked me, “what kind of rabbi will perform the ceremony?”

There was a long pause. I tried to think of an appropriate answer.

Finally, I said: “A Jewish rabbi.”

He smiled and said, to my great relief, “Well, that’s alright.”

Read More: https://www.amny.com/news/spotlight-on-n-y-u-and-drugs-after-bust/