By Martin Sokolinsky

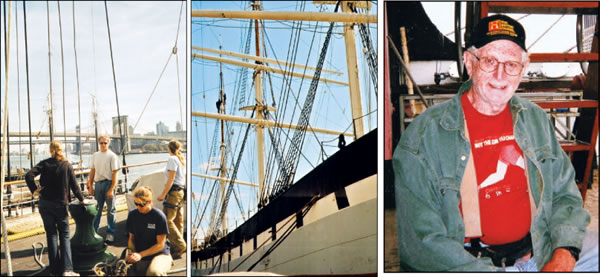

On a pleasant morning last month, the weekend volunteers at the South Street Seaport were waiting for help to arrive.

The wooden upper masts of the Wavertree had to come down. Everyone knew that they were rotten — particularly, the foretopmast. Instead of solid wood, this mast was a painted shell concealing rot that looked like coffee grounds. In fact, one volunteer climbed to the foretop and shoved his whole arm right through the lower end of the decayed spar.

Charlie Deroko, the waterfront director at the South Street Seaport Museum, sent an urgent message to master rigger Jim Barry of Rhode Island: Can you strike our dry-rotten wooden spars using only traditional methods? We simply lack enough trained personnel to get all that top-hamper to deck without an accident.

Wavertree, a 123-year-old iron windjammer, had once had her masts taken down — the hard way. In 1910 she was dismasted off Cape Horn. Her falling mainmast sent iron yards weighing two tons each crashing down in a tangle of sails and rigging. Several crewmembers wound up in the hospital in Port Stanley, Falkland Islands, their ribs and legs broken.

In accepting this particular South Street Seaport assignment, Barry would be putting his career — perhaps, his life -— on the line. Museum ships like Wavertree are like bridges: If you don’t keep painting them, they rust, they fall apart. With only three paid hands covering five old vessels, it’s impossible for the museum to provide constant maintenance. And nothing is quite as treacherous as lowering dry-rotten spars, or walking out on a hollow steel yard when braces, lifts, halyards or sheets are being maneuvered.

I was aboard the ship, awaiting Barry’s arrival, like the other weekend volunteers. All of them were at least 30 years my junior. Me, I thought I was just there to write an article about a Rhode Islander coming to drop the Wavertree’s upper masts and yards. And unlike the others I hadn’t donned any climbing harness or steel-toed boots. I’d come armed with nothing but a notebook and camera.

Before Jim Barry arrived, the museum’s veteran waterfront supervisor, Charlie Deroko, had asked us weekend volunteers to lower the spanker boom and then shift it forward from the quarterdeck to the main deck. It was an insignificant task compared to what Barry would be facing. But the exercise did give us a foretaste of things to come. We were raising the 1,200-pound boom from its gooseneck until — bang! — a large snatch block popped six feet in the air when an eyebolt pulled out of the rotten deck.

Barry appeared shortly before sundown that October day. This wizard from Riverside, R.I. had sent aloft 19 spars on the Wavertree for Operation Sail in 2000. And he managed to get it done in just three weeks. Later, he restored the rigging of Glen Lee in Glasgow, Scotland, and served as chief rigger on the Johnnie Depp movie, “Pirates of the Caribbean.”

This time, Barry brought an entourage of eight riggers, a stable of young acrobats, recent college grads.

We knew that the iron three-masted ship Balclutha in San Francisco had faced a similar situation in June 2007. Her foretopgallant mast was so badly dry-rotten that it had to be sent down. And her rigging crew (U.S. Park Service staff and weekend volunteers) also tried to employ traditional methods — that is, no cranes or cherry-pickers.

No sooner did they attempt to strike Balclutha’s spars than the decaying topgallant mast snapped. Both mast and yard were canted at a 90-degree angle, caught in the tangle of stays and shrouds. Fortunately, no one was hurt, but the S.F. rigging crew had to make an urgent call for a barge-mounted crane.

On the Wavertree the next morning, luckily, the weather remained dry. (In foul weather, rigging work aloft becomes exceedingly dangerous.) Barry told his crew that they would begin by taking off the ship’s four wooden yards. Then, they would also drop the relatively light, third-stage masts. But the remaining wooden spars would be left in place. Since Wavertree was scheduled to go into a shipyard, giant cranes there could safely remove her other masts.

I breathed a sigh of relief. Barry had decided that Wavertree’s 53-foot topmasts were too decayed to allow his spunky riggers to deal with them. Instead, they would only drop the 49-foot topgallant masts — each weighing something under one ton. Of course, all wooden yards had to come down as well.

“We’re relieving each topmast of a three-ton burden,” Barry told the rigging gang. “So your work in the next week or so should render them a lot safer.”

I saw Barry’s crew using small walkie-talkies at first. One fellow told me they kept getting the channels mixed up. So they started shouting: “ALOFT THERE!” and someone high in the rigging would respond: “DECK AYE!” I had lots of trouble distinguishing where voices were coming from — hadn’t the doctor recently advised me to wear a hearing aid?

Barry sent two young riggers up to each topgallant mast where they stood on the spreaders, those long angle irons about three inches wide. And I mean they really stood. Like for a whole day. First, they lowered wooden yards to deck. Next, they stripped the mast of its gear using large adjustable wrenches and crowbars. I had to marvel at how Barry’s youthful gang, perched on the spreaders, always managed to hang onto tools. Nothing ever slipped from their hands although, once, the fairly heavy iron pin on a parral basket of the mizzen lower topsail yard shattered and made a dent in our temporary plywood deck. Fortunately, wire-rope lifts still supported the yard and no one was standing directly underneath.

When his young riggers were starting to lower the mizzen topgallant yard, Barry saw how it sagged at either end, suggesting that the center of the spar was rotten and might crack in half. As a stiffener, a 15-foot length of four-inch pipe was sent up and the crew fished it to the middle of the yard. In the end, they managed to bring down that decaying spar in one piece.

My problem aboard Wavertree was — Jim Barry’s dog, Jack.

This was because our mainmast had no ratlines, or rope steps leading from the topmast rigging to the spreaders. Of course, athletic people like Barry’s crew might be able to haul themselves up the sides of the ladder — they didn’t need any rungs. But it seemed rather inhospitable of us. So, with Barry’s permission, I climbed up 100 feet to measure the distance between the shrouds. Then I came down and started eye-splicing the two rope ratlines. That’s when his dog started snapping at me. Nobody seemed to pay attention to this. Barry’s girlfriend, Karinna, explained that the dog was just feeling neglected. But I still had to walk in a wide circle to dodge Jack’s teeth. The overly playful pet managed to get a mouthful of my trousers while I was cutting Dacron rope with a propane torch.

I was almost glad to get back aloft and away from Jack’s mood swings. Hanging safely off a spreader one hundred feet in the air, I called down to have my bucket of tools sent up on a gantline. Because there was so little time, I was using my sit-harness in lieu of a chair. Somehow I felt comfortable enough. Finally, I stepped on each new ratline, testing them with my full weight. They were just temporary but held okay. Wow, when I’d entered the No. 2 train on my way to South St. that very morning, a young man had offered me his seat! I felt great.

When I got down to the table in the ship’s saloon, the riggers had all but finished lunch. But I felt as if I had just scored a touchdown. I forgot I was supposed to be writing about them, taking pictures of them and kept on talking happily until Barry announced: “Back to work, everybody!”