By Harry Newman

“Maria de Buenos Aires”

Directed and Choreographed by David Parsons and Pablo Pugliese

Performed by Parsons Dance Company

with Nicole Piccolomini, Diego Arciniegas, and Ricardo Herrera

September 26, 28, 29

A production of Gotham Chamber Opera Skirball Center for the Performing Arts

New York University

566 La Guardia Place

(212-279-4200; gothamchamberopera.org)

“Where’s the birthing table? We need the birthing table!”

It’s the second day of rehearsals for the full company of “Maria de Buenos Aires,” the rarely-produced opera by tango legend Astor Piazzolla, and director David Parsons is excited.

A dancer rushes a table to a spot upstage and rehearsal resumes. A street scene: dancers moving in more and more intricate loops around the space, exaggerating and amplifying patterns of foot traffic. The music builds in intensity and tempo. Singers join in. A man tries to make his way across the stage looking for Maria who may be a woman of the Buenos Aires demimonde or the spirit of tango or the Virgin Mary or all three.

“You see?” says Parsons, filling in the scene. “It builds and builds.”

Behind them, a woman appears on the verge of give birth, drawing the crowd closer to her. They’re awed, stunned. It looks like The Nativity. Then a young woman, the child, rises above the crowd, floating in the air a moment before being brought down to earth.

“But instead of a Christ child,” Parsons continues, “it’s another Maria who’s born, who’s going to face all the same shit, and the whole thing starts all over.”

Next week at New York University’s Skirball Center, the Gotham Chamber Opera will premiere its version of “Maria de Buenos Aires,” one of the neglected gems of 20th century music theater. First performed in 1968, it was a key work in Piazzolla’s revolutionizing of the tango, transforming it from dance music to concert music by bringing in elements of jazz and classical composition for the first time. Widely regarded as tango’s greatest innovator, he broadened the creative and emotional possibilities of the form and gave it new vibrancy.

As much song cycle or extended tango suite as an opera, “Maria de Buenos Aires” is based on a set of complex, highly evocative poems by Horacio Ferrer, Piazzolla’s longtime collaborator, and is open to many interpretations. It can be a story of a young woman in Buenos Aires, a stylized recounting of the history of tango (the music includes several song styles from milonga, tango’s 19th century precursor, to Piazzolla’s most contemporary variations), or a skewed religious allegory. The text is filled with surreal elements including a goblin as the narrator, drunk marionettes, the voice of a Sunday morning, masons who are Magis, and a chorus of psychoanalysts.

“The Piazzolla’s a major challenge,” said Neal Goren, Gotham Chamber Opera’s founder and Artistic Director, “because the text is incredibly abstract. It’s not like there’s a clear and concise story line from beginning to end. You have to mine the text for a story line. So I thought what could really represent that abstraction well is choreography.”

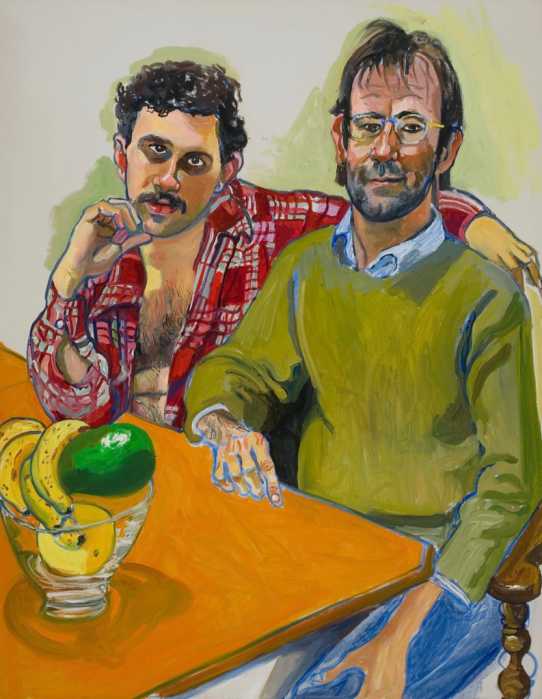

That led him to the idea of choosing a choreographer instead of a theater director to direct the production, which eventually led him to David Parsons. One of the dominating figures of American modern dance of the last three decades, first as lead dancer with Paul Taylor and other artists and for the last twenty years as director of his own Parsons Dance Company, Parsons is known for his inventive, physically exacting, and exuberant choreography. His work is characterized by its keen dramatic sensibility, extraordinary presence, and a profound sensuality.

“When I saw David’s work, I knew he was absolutely [right] for it,” Goren elaborated. “He has a huge range in his choreography. It can be incredibly sexy, incredibly mysterious — which are two qualities of this piece — incredibly violent, but also incredibly loose. He can be funny, he can be serious. I thought he could handle the emotional range of the Piazzolla, which is enormous.”

It’s an enormous undertaking for Parsons as well, who has never directed for the stage. But he seems to be relishing it. “I’ve been choreographing 36 years,” he said in an interview after rehearsal, joined by Pablo Pugliese, the assistant director and co-choreographer on the show. “One of the hard things about being an artist year after year is just keeping it going, getting excited, [getting] yourself into a new situation.”

They started working on the story together about a year ago. Pugliese, the son of two of Argentina’s most famed tango dancers and an internationally-known tango choreographer-performer himself, was first brought in to advise on dance aspects of the project. But he was soon made an equal partner in the collaboration because of his knowledge of the piece, understanding of the music, and experience in the world of tango.

They decided to focus on Maria and root the production in the story of a real woman and her experiences instead of an archetype. “I didn’t want it to be totally abstract,” Parsons continued. “The libretto’s abstract enough. And the story is so fantastical. I thought it would be more emotionally arresting for the audience to take a journey with Maria. We did a lot of work on that.”

The story follows Maria as she moves from the provinces to the city, lured by a spirit of adventure and mystery (embodied by the tango and its signature instrument, the bandoneon). The romance fades quickly and she ends up being a prostitute. She dies and is condemned to wander the streets of Buenos Aires as a shadow, until she returns to life again in a different form.

Ordinarily performed in a concert setting with three soloists and a tango orchestra (when it’s done at all), Parsons’ instead offers a fully staged, theatrical imagining of the opera, probably the first ever. He utilizes his entire company of ten dancers in the work, often to startling effect. Rather than the dance interludes you might expect, movement is integrated throughout the 90-minute piece, in many ways transforming it into a kind of dance opera. There’s constant motion, enhancing and reinforcing the story as it unfolds. The singers and narrator are incorporated fully into the choreography as well. In a sense, quite appropriately for a piece like this, dance becomes the environment in which the story is told. The result is a stunning and original hybrid of many different forms.

It was a conscious choice. As they started working on the choreography in the spring, Parsons and Pugliese sought to emulate in the movement what Piazzolla did in music, expanding the boundaries by bringing together different traditions into a choreographic whole.

“We were trying to come up with language that had tango powerfully [in it],” explained Pugliese, “the same way that tango and opera are blended in the piece. At the very beginning we [worked] on having dancers learn very basic original tango movements, so they would get the flavor of it. [That way] anything we’d choreograph after would have the sense and feel of the dynamics of tango, the leading and following.”

“We feel very comfortable with the style we’ve come up with,” Parsons added. “The feel, the whole vibe is really good. The language, the choreography, how the contemporary [blends with the traditional].”

One of the most affecting aspects of the production is the use of doubling. Each of the three performers — Maria, El Duende (the narrator), and Porteño, who sings multiple roles in the piece — have dancers paired with them throughout the performance, portraying in movement the internal circumstances of the characters or scenes. This isn’t mirroring or duplicating what characters are doing, but expressing the emotional resonances and undercurrents of what they are going through, beyond what they may even realize themselves. We see the longing and hurt that lies under an expression of determination or the scorn that comes with professions of love.

Now, since the singers and narrator joined rehearsals earlier this month, it’s starting to come together.

“We’re in good shape,” concluded Parsons. “We’ve just been working on it for so long…The object is to stay open and not close everything off. Let it tell you. Sit back and listen to what the piece is telling you. It’s starting to tell us what to do and that’s when you’re lucky.”