BY YANAN WANG | Following this week’s official launch of Citi Bike, the new bike share program organized by the Department of Transportation (DOT), residents can expect to see cyclists take the city streets in full force — but at what cost?

The program, which puts 6,000 bikes and over 300 docking stations across Manhattan and Brooklyn, is the largest of its kind in North America. Since its ubiquitous gray racks began appearing along streets several weeks ago, Citi Bike has been the subject of both excitement and controversy, with Chelsea residents expressing reactions ranging from approval and enthusiasm to fervent opposition.

“The concept of bike share is great. We need it in New York City,” said Steven Shore, an attorney leading a lawsuit against the DOT for the inappropriate placement of one docking rack in Greenwich Village. “But the implementation of the program has been grossly mishandled and ill-conceived.”

Community Board 4 (CB4) District Manager Bob Benfatto said the program has been “a long time coming,” adding that “at least two [CB4] meetings,” open to the public, have been held in regards to Citi Bike. During the initiative’s kick-off process, Benfatto noted, officials from the DOT attended board meetings to address public concerns.

Compromise on 22nd Street: This docking station was relocated from in front of historic homes to along Clement Clarke Moore Park.

The Nuts & Bolts of Citi Bike

• Annual membership (includes key for all docking stations): $95

• Weekly pass (paid by credit or debit card at station): $25

• Daily pass (paid by credit or debit card at station): $9.95

• Weekly and daily pass holders receive a ride code at the kiosk, which can then be entered into the keypad on any dock. Keys for Annual Members will work in the key slot at any dock. Annual Members may ride for 45 minutes per trip, while weekly and daily pass holders may ride for 30 minutes. The bike can be returned to any station in the city within this period of time, after which the user incurs overtime fees for each following half hour.

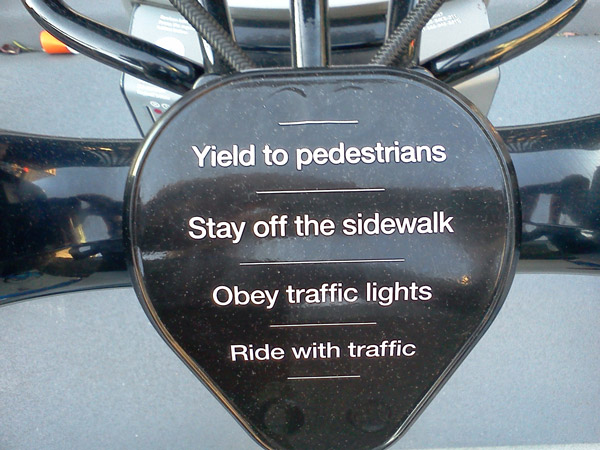

• If the user cannot return the bike because a dock is full, they may request a time credit of 15 minutes (no additional charge) at the kiosk, where they will be directed to the nearest station with available racks. The instructions on each bike’s handlebar read: “Yield to pedestrians,” “Stay off the sidewalk,” “Obey traffic lights” and “Ride with traffic.”

• Annual Members receive helmet discounts with their registration. Launch for all users on June 2. Visit citibikenyc.com for a station map and further details.

Many residents, however, have expressed frustration with the way in which the bike racks have appeared — largely without forewarning to homeowners or businesses situated near the new stations. Annual memberships were activated on Memorial Day, and the program will launch for all users on June 2. Issues of public safety and the effectiveness of the program in eliminating automobile use will be just as pressing as the question of what impact the placement of Citi Bike docking stations will have on the layout and movement of the city.

BUILT TO LAST, NOT FOR SPEED

A Citi Bike is not your regular bike. Since the vehicles are heavier and have less maneuverability, it may take even the most seasoned cyclists a few tries before they can ride them with ease. According to Zoe Cheswick of Bike New York (BNY), an educational partner of Citi Bike, all of these design elements were carefully selected to make the program safer for its users.

“Citi Bikes have a different turning radius, because they don’t want people weaving in and out of traffic,” Cheswick explained. “They want it to be that wonderful bike that gets you from point A to point B.”

Up for grabs, on 14th St. and Tenth Ave.

Cheswick is one of the BNY instructors who is leading a workshop geared specifically toward introducing people to Citi Bike. Since April 10, these informational sessions (continuing indefinitely) have been running once a week in two different locations (Brooklyn and Bicycle Habitat in Manhattan), and they each host about 35 to 40 people. The class is a spin on BNY’s traditional “Street Skills” class, and attendees are taught the basics about the bike share program: how to take the bike out of a kiosk, what to look out for on the road, what options they have for using the bikes — annual membership is $95, a weekly pass is $25 and a daily pass is $9.95. As Chelsea Now went to press, an estimated 16,500 people had purchased annual memberships.

The biggest safety concern, Cheswick noted, is that the city may experience a sudden influx of inexperienced riders — people who either have little experience with biking or who have not ridden bikes for some time.

“We strongly encourage being predictable,” she said. “Know that you’re being considered just like a car, and obey traffic laws.”

Some prospective users are optimistic that Citi Bike will improve the relationship between drivers and cyclists on the road. Gary Roth, a Chelsea resident and an Adjunct Professor in the Urban Planning program at Columbia University, said he thinks an increase in bikes will make the city’s streets safer for all.

When there are more cyclists on the road, Roth noted, drivers become more aware of them. As a result, cars will slow down and drive more cautiously. He added that as an avid bike rider, his level of automobile use is virtually zero.

“The cars are the 800-pound gorillas,” said Roth. “Bikes want to share. We just want a little peace [on the road].” He observed that people do not ride bikes in New York City because they are frightened. Once the Citi Bike program gives the cycling community “strength in numbers,” there will be a healthier balance between automobiles and bikes, Roth said.

While the goal of Citi Bike’s collaboration with BNY is to prepare people to use the program, it does not account for the tourists who will be taking advantage of bike share. Cheswick said the educational programming is still in its infancy, and they hope to do work with tourists in the future.

In the May 23 edition of our sister publication, The Villager, Lincoln Anderson addressed the practical functions of the Citi Bike design. With just three standard gears, the bikes were built to prevent their users from going too fast. While Anderson wrote that the speed limitation left him “underwhelmed,” he was confident that the vehicles would not be “careening out of control,” as Citi Bike has opted for a combination of “safe and slow.”

In further preparation for the new waves of bike riders, the DOT has given away more than 75,000 helmets, said department spokesman Nicholas Mosquera. Citi Bike will also be offering helmet discounts to new members and “learn to ride” workshops across the city.

STATIONS SUDDENLY APPEAR

When an Emergency Medical Services crew arrived in front of Greenwich Village’s Cambridge co-op building in response to a 911 call on May 19, they were met with an unexpected obstruction — a row of Citi Bike racks, installed a few weeks ago to the displeasure of the building’s owners, blocked the entrance to the building.

The New York Post reported that due to the length of the racks, the ambulance had to find parking a distance away from the building, slowing down the process of getting Edward Liss, a resident who had suffered from a heart attack, into the emergency vehicle. Steven Shore of Ganfer & Shore, LLP, the law firm that represents the building, criticized the DOT for poor choice of placement.

“Whoever determined the location of these stations could not have been making a reasoned decision,” Shore told Chelsea Now. While the racks in front of the entrance were removed shortly after the EMS incident, Shore noted that The Cambridge will be going ahead with its lawsuit against the DOT, citing the department’s “failure to comply with a host of regulations.”

In the case’s official petition, the firm argues both that “the DOT’s decision was arbitrary and capricious” and that it “failed to conduct the required environmental review.” The report mentions traffic guideline violations, the lack of prior notice given to the building’s residents and the use of advertising on what could be categorized as “street furniture.”

Shore added that the racks were removed only after he had threatened the city with an emergency order with the court. As a member of Save Chelsea, Shore has received a number of requests from other people seeking to launch lawsuits against the DOT for the bike stations.

One such individual is Carolynn Meinhardt, a longtime Chelsea resident and head of the Chelsea Historic District Council. She said the placement of two docking stations within the historic district came as a shock to her.

“They just snuck in during the middle of the night. Nobody even saw the construction,” Meinhardt said, adding that it “could not be more inappropriate” for racks to be placed in a community otherwise governed by stringent regulations in line with its historic district designation.

“When you live in a historic district,” she noted, “you are governed by every possible control — the color that you paint your windows, the color that you paint your door, how you deal with the iron fence. If you want to build a new building, that all has to be reviewed by the landmark commission.” Meinhardt said she “blames CB4,” adding that her calls to the board have gone unanswered.

But Benfatto said the board is forwarding all Citi Bike-related complaints to the DOT, as well as sending in specific requests for the removal of stations from certain sites around the neighborhood. Benfatto estimated that they have received around 20 complaints. “The two most vociferous,” he said, were “from people on 20th Street, where there is the historic block, and 47th Street.”

In the second case, the Citi Bike station had been placed on the street side rather than the avenue side — the latter being the placement Benfatto and other CB4 members had requested during a walk-through with the DOT in which the two parties discussed possible rack locations.

“In some cases they did what we asked, some cases they didn’t,” Benfatto remarked, adding that he was hopeful the DOT will be open to further negotiation once the program is up and running. “The stations are moveable,” Benfatto emphasized. “The truck can come, pull them out of the ground and take them away. It’s not a big deal.”

NIMBY FOR SOME, ENVY FOR OTHERS

Stephanie Gartner was out walking her dog last Wednesday when she noticed a Citi Bike docking station outside the Google Building (formerly the Port Authority Building on West 16th Street and Ninth Avenue). A longtime Chelsea resident, Gartner is wary of the impact that the bike share program will have on a community she holds dear.

“I think [the racks] are obtrusive,” said Gartner. “They make the streets dirty, and a lot of people are going to get killed.” While many people would be more than happy to see the bikes removed from their block, others are envious.

“There’s no docking station near my house, and that’s a problem,” Roth lamented. “If they want to move them from 22nd, I’d be happy to have them on 24th.” He referred to the racks currently located along Clement Clarke Moore Park, where they were moved last Wednesday after originally being placed along a row of homes on the north side of 22nd Street.

For individuals with storefronts not directly affected by the racks, there is the hope that nearby Citi Bike stations will be a boon to business.

Deanna Tutta, the manager of Flor de Sol Tapas Restaurant and Bar (on West 16th Street and 10th Avenue), said she hopes that people stopping at the bike station along the side of the restaurant will also be inclined to come in for a bite to eat. Tutta noted as well that even though it is unfortunate the program “sucks up all the parking,” it is important to do “whatever is healthier for the city.”

The owner of the MRK Halal Food cart (on Ninth Avenue and West 16th Street, near the docking station outside of the Google building) was inclined to agree. “It’s good for us,” said Sayed Alandour. “People chilling by the bike station might be hungry and want to come buy food.”

Some people have taken issue with the bike share program’s connection to a large, privately-owned business entity. Although it maintains a visual presence on the bikes and docking stations, corporate sponsor Citibank has no involvement in the program’s daily operations (which are managed by NYC Bike Share LLC).

Citibank reportedly paid $41 million to be the program’s head sponsor for the next five years — a title that not only allowed it to impact the naming of the initiative, but also virtually gives it advertising space on every bike and docking station, where Citi Bike’s emblazoned logo is reminiscent of the bank’s own.

“[Citi Bike] is not a bike ‘share’ program any more than Hertz Rent-A-Car is a car ‘share’ program,” said Stanley Bulbach, head of the West 15th Street 100 & 200 Block Association. Because of the initiative’s close relationship with a commercial operation, Bulbach advocated for a change in vocabulary, arguing that it should instead be referred to as a “bike rental.”

According to Shore, Citibank’s business tactic means that some docking stations are in direct violation of the law. “The landmark law states that advertising shouldn’t be on the side streets of historic districts,” Shore said. “Why are they there? There’s plenty of space in other areas.”

It might be a matter of simply getting rid of a station or two. Bill Borock, President of the Council of Chelsea Block Associations, pointed out that most of the community opposition is not directed at the bike program itself, nor is it a battle between cyclists and drivers: “I’m a car owner, but I have no problem with bike riders,” Borock said. “We just think there are too many bike stations. One of the ongoing problems with city services is enforcement. If the DOT doesn’t follow up with some of these concerns, it becomes a quality of life issue.”

Curious about how to use Citi Bike? Google it!