BY CLAYTON PATTERSON | It is hard to wrap one’s head around the death of a person at the hands of the N.Y.P.D., especially for something as incidental as selling loose cigarettes.

In order to make the arrest of Eric Garner, the cops aggressively roll up on him. As they approach him, a cop reaches for Garner’s wrist and starts the arrest. A common response to this kind of action is to pull one’s arms away and ask what he or she is being arrested for, but by then the situation is out of control.

We now have resisting arrest and a full-on takedown, resulting in an arrest. It seems that it is time to look at police procedures and education.

Beginning on the night of Aug. 6, 1988, there was a protest over a curfew in Tompkins Square Park that resulted in what was subsequently dubbed a police riot.

The previous week, the cops in the park had been involved in what they perceived to have been a compromised situation with some local anarchists. The police felt they needed to instill some respect for authority, so they convinced the community board to set a curfew on Tompkins Square Park, the only park in the city without a curfew.

The cops made a deal with the homeless and the other late-night park hang arounds that they could stay in Tompkins as long as they kept away from the front section of the park, by the Avenue A and St. Mark’s Place entrance.

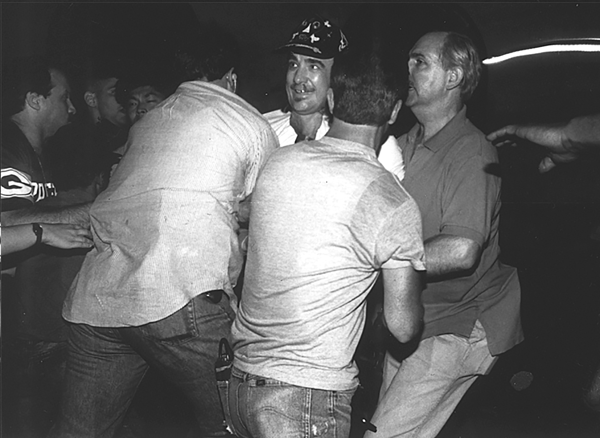

Within minutes, the park’s front section was cleared and the conflict began to get out of hand. The angry police charged out of the park and into the streets, indiscriminately attacking anyone in their path, beating and shoving those who happened to have the misfortune to be on the streets.

Eventually, the police settled on Avenue A and E. Sixth St. At least that is the location where I spent the rest of the night with Elsa. At 6 a.m. the curfew was over, the park was back open, and Elsa and I ended up with a 3-hour-and-33-minute videotape of the night’s goings-on.

The tape exposed much police misconduct. There were more than 125 complaints related to police violence, and numerous residents — most of them unrelated to the protest — ended up in the hospital. These people had just been at the wrong place at the wrong time.

The evidence on the tape led to six cops being criminally indicted, the Ninth Precinct captain moving out of the precinct, cops fired. But the most damning detail was the part of the tape where a commanding officer was attempting to exercise some control over the situation. The lower-ranking cops, however, paid no attention and took off chasing protesters. There was no respect for authority or the chain of command.

The tape was a breakthrough in the use of the new technology, Civilian Journalism, the community’s defense against police misconduct. However, it sent me into 20 years worth of criminal, civil and departmental court battles, numerous arrests, and an inside look and education into the inner workings of the judicial system.

It also was the beginning of a period of four solid years worth of protests, a number of riots, hundreds of arrests, and the reorganizing of the N.Y.P.D. In addition to my record of the events, there was another authoritative 20-minute videotape taken that night by Paul Garrin.

In short, the Lower East Side became a hands-on training ground for the N.Y.P.D. On Aug. 6, 1988, cops on horses, in helicopters, along with several hundred riot police and a command center could not close a 10.5-acre park on the L.E.S.

But by 1992, the police could control the streets. In 2001, the cops, in a couple of hours, were able to shut down three airports, and all the bridges, tunnels, ferries, railways, subways, buses and street traffic.

Early on, the focus of the protests was on police brutality, the ineffective Civilian Complaint Review Board (C.C.R.B.), the effort to impose a park curfew, the homeless crisis, the closing of the park, the tearing down of the park’s band shell, the housing crisis, squat evictions and the encroaching gentrification that was starting to take over the neighborhood.

In the beginning, it was ranking cops, like Captain Fry, pushing the blue shirts with his nightstick, screaming, “Form a line, form a line.”

It was not unusual for a protest to go on for more than a day. For the cops, it was an overtime bonanza. During that time, a cop retired at his last year’s salary. It was possible to retire at double salary. For the smart commander, it became a golden ladder moving up the chain of command.

Several chiefs of police came out of the struggle, including Hoehl, Julian, Gelphan and Esposito. Esposito boasted that he would never have become a chief it had not been for the Tompkins Square Park conflicts.

Dinkins became mayor and the administration focused on reorganizing the Police Department. Many older cops retired, and a new crop of younger cops was hired. The new Mollen Commission cleaned out a number of cops involved in the illegal drug business and started to centralize the department.

The protesters could rule the L.E.S. streets until 1992. The police practiced different forms of organizing, including putting one sergeant in charge of six cops. They brought in scooters, tried a wedge formation, and after practice, practice, practice, by 1992 they gained control of the streets. If a protester stepped into the street, he would be arrested.

The Police Riot was at the end of Koch’s third term. The department’s reorganization was under Dinkins. Giuliani inherited a well-organized, razor-sharp, paramilitary Police Department. Giuliani brought in Bratton as his police commissioner. Bratton partnered with the transit cop Jack Maple, and they changed the streets of New York City, probably forever.

Bratton and Maple were influenced by the concept Safe Streets, which allowed police to believe that if they concentrated on petty crime, the number of more serious crimes would be cut. If the police could stop people from hanging out on street corners, in front of bodegas and outside the projects, that would thwart the opportunities of street criminal activity and would help bring order to a community.

Bratton’s zero-tolerance policy initiated programs like stop-and-frisk. At the same time, Bratton worked on making the department more ethically diverse.

Bratton was as hard on the precinct commanders as he was on those residents who were active in the inner-city street culture. He was influenced by a new community police management philosophy called Comp Stat — an analysis of computer statistics on crime for each precinct.

A main focus of CompStat was holding commanders accountable for any rise in crime in their precincts. Crime took a dramatic downturn, and Bratton became the darling of mainstream America, even making the cover of TIME magazine — though he was not such a hero to many in the inner-city minority community.

But in a universe where Giuliani had to be the center of attention, Bratton’s success became his downfall, and soon he was pushed out the door.

Ghosts from the past can reappear. Bratton comes back as de Blasio’s police commissioner, and ex-Mayor Giuliani becomes an expert commentator for Fox TV.

Giuliani’s tendency is to find fault in most black leaders — including President Obama, Attorney General Holder, Al Sharpton — and talk about family values.

Yet, there is no question that Giuliani ended all the costly squat-eviction protests on the L.E.S. the day he made the remaining buildings legal, and the squatters became property owners.

During the L.E.S. years of turmoil, the cops who became police chiefs had the ability and the expertise to deal with both the cops and the protesters, as well as, to appease City Hall. This was a delicate balance. The chief had to keep a close rein on the cops, as there were some who had the tendency to take the law into their own hands, with the belief that they had the right to deal out justice by inflicting severe punishment with the use of their nightstick.

If a commander was too aggressive and antagonistic toward the protesters, the end result could be a riot, or at the very least, injured protesters or cops, and a conflict that could go on for a long period of time.

On the other hand, to maintain respect and to have the confidence of the rank-and-file cops, the commander could not be perceived as being too passive or compromising in any way.

Police chiefs also had to evaluate whether the arrest was worth clogging the criminal courts or if a ticket would suffice. It was all about the bottom line.

There were many times during the years of protests when the tensions between the protesters and the cops were high. But never, from what I am aware of, did anyone intentionally try to maim a cop. There were certainly no plots to kill a cop.

Considering how many battles were fought, there were few permanent injuries on either side of the conflict. There is no question that there was hardcore resistance on both fronts, just as each side had their own radicals. The radical protesters did random acts of vandalism, broke windows, set fires on the street and burned down a homeless camp before it was evicted. They spray-painted resistance graffiti, threw bottles, flattened a few tires, but did not use Molotov cocktails, or any kind of deadly force.

The radical cops would pepper-spray protesters in the eyes, whack people on the head with their nightsticks. They would also target individuals by making a questionable arrest and trump up the charges. And after an arrest, cops would bend the handcuffs, which caused severe pain, or tighten the handcuffs to the point of causing the hands to go numb.

Another trick was they would make up a false complaint, go to an approachable judge, and get a search warrant.

Both sides made verbal threats to each other. As time went on, though, the equation changed and there is no question that the police had more power.

The recent vitriolic rhetoric by Patrick Lynch, the head of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association — blaming the mayor, civil rights leaders and protesters for contributing to the killing of the two cops — is using a terrible tragedy for political grandstanding. Perhaps he is making a play for his next election, or he is losing control.

The cops turning their backs on the mayor — their boss, our elected official — is disregarding the will of the people, and is not only disrespectful but dangerous.

I understand why white Americans — especially white cops — dislike Al Sharpton. He has the ability both to hold the system accountable and to bring mass public attention to a questionable death of a black person at the hands of the police. But he never calls for violence. Protests and free speech are protected under the Constitution.

De Blasio, as a mayor of all of the people, was trying to be protect the rights of the protesters to express their point of view, and to give the cops enough authority to take control if a situation got out of hand, which I am sure the N.Y.P.D. can do. Too much resistance can incite violence and unnecessary hostility. Most protests will remain peaceful and “walk themselves out.”

My experience taught me that the masses just want a way to express their outrage, not be violent. If you stop the protest march from crossing a bridge, the mass blockage stops traffic. If they march across the bridge, the inconvenience passes with the march. They need an end goal where they can hold a protest rally.

The solution Lynch is suggesting — to give the police the ultimate authority — would mean we are living in a police state. And what is the problem with de Blasio, even as mayor, telling his children that because they are black, it can mean dealing with a different set of rules?

No, I do not believe most cops are racist. The system is set up to be unequal. The divisions are wide.

It took me a few years of living in a drug-saturated community to get an inside look at who sells drugs, who buys drugs, who uses drugs, the institutional racial discrimination.

Starting with Operation Pressure Point in 1984, hundreds of people involved in the illegal drug business went to jail — and with the Rockefeller Drug Laws, it was not unheard of to get a sentence of 20 years or more.

Over the years, hundreds of people involved in the drug trade were incarcerated. That is the law. But what the law doesn’t explain is why most of the people in jail are black and Hispanic. The majority of people coming into our community to buy drugs were white, often from New Jersey. It is a common practice for a buyer to be supplying more than just him- or herself.

After President Reagan was elected, it was no secret: It was snowing cocaine on Wall St. Back then, there was all the glamour connected to cocaine — using hundred-dollar bills or specially designed gold spoons to sniff the powder, the keychain ornaments to hold your coke, the razorblade jewelry.

The out-of-control celebrity types were being habitually arrested and going to rehab, and there were the oft-told public tales of rock’n’rollers’ use of illegal drugs, the Mollen Commission’s findings exposing the drug-related corruption in the Police Department, and on and on.

Yet, the prison system does not reflect this difference. Illegal drugs are everywhere. Yet the ones ending up in jail are black or Hispanic. Just as the majority of individuals who end up dead in a situation involving the police are black men.

We are in self-denial if we cannot see this point. We need an Al Sharpton to keep us aware of what is going on. Let the courts settle the matter.

I believe the majority of New Yorkers — certainly including the mayor, Al Sharpton and most of the protesters — are outraged two police officers were assassinated. It is time for a little restraint and to start to actually deal with our social problems before things spin completely out of control. There have to be splits in the Police Department as the rhetoric starts to become so divisive.

In the end, the police proved that by having a disciplined force, competent experienced leaders, using standard police procedure, they could control the streets. I am not sure how things got so out of control that the police needed to become so militarized. How did the police become so afraid of the citizens they are paid to protect?