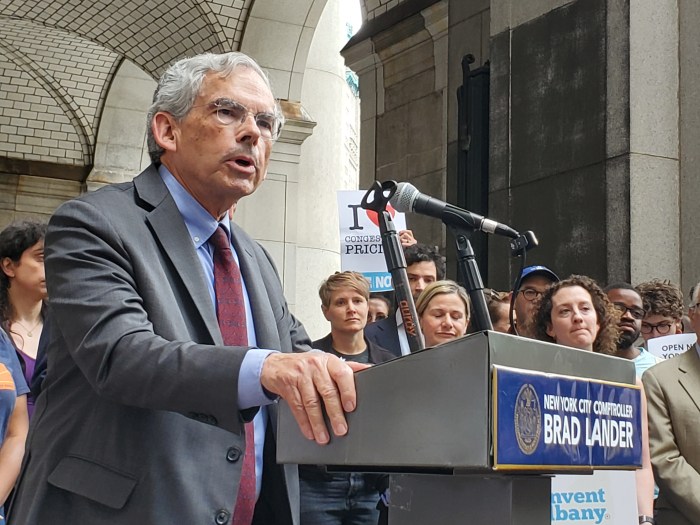

City Comptroller Brad Lander said Wednesday that he is assembling a coalition of legal minds and impacted parties to potentially sue New York state over Gov. Kathy Hochul’s eleventh-hour decision to indefinitely pause congestion pricing.

Because the governor framed her decision as a “temporary pause,” and the original start date of June 30 for the $15 congestion toll in Manhattan has not yet passed, Lander and others do not believe the time is ripe to bring a suit. Still, the city’s financial watchdog has brought together top legal minds in public interest practice; advocates for transit, the environment, and disability rights; and representatives of the city’s business community to develop legal strategies for one or more lawsuits seeking to compel the state to move forward with the Manhattan toll plan.

It’s an ironic twist in the congestion pricing saga; before Hochul announced the indefinite pause, no fewer than six lawsuits had been filed against the state, the MTA and/or the federal government to derail congestion pricing.

Now, Lander could be looking to litigation to save the program.

“The governor’s sudden and potentially illegal reversal wronged a host of New Yorkers, who have a right to what was long promised to all of New York,” Lander said at a Wednesday press conference in Lower Manhattan. “We are exploring all possible legal responses to the governor’s decision, which may violate multiple provisions of New York State law.”

Potential plaintiffs include residents and businesses in Manhattan’s central business district adversely impacted by punishing New York City gridlock. Other possibilities include MTA Board members who voted to approve the tolling plan and would potentially violate their fiduciary duty to the agency by defunding it of $15 billion for construction and maintenance work, plus MTA bondholders whose investment could tank from a potential credit downgrade.

The city’s pension funds own a small number of MTA bonds, about $31,000 worth — and because of that, Lander is deliberating with attorneys on whether he, himself, can sue as well in his capacity as comptroller, he said.

The list also includes New Yorkers with disabilities, who struggle to move around a city with a transit system that’s only 30% accessible. In 2022, the MTA settled a pair of lawsuits brought by disability advocates and, in doing so, agreed to make 95% of all subway stops fully accessible by 2055. Congestion pricing money was going to pay for a large chunk of that, and now the authority’s ability to meet even that lengthy mandate is in question.

“We always have to settle, we’re always shortchanged, we had to settle for 95% elevator access,” said Sharon McLennon-Wier, executive director of the Center for the Independence of the Disabled New York. “We supported congestion pricing because we were told that it would pay for all accessibility, and accessibility does not mean just elevators.”

Overriding Hochul?

The coalition believes it has multiple viable legal avenues to persuade a judge to order congestion pricing’s start against the governor’s wishes.

It could sue under the state’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, which requires all state agencies to conduct business in a manner keeping with an overarching goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

There’s also the 2021 Green Amendment approved by New York voters, affirming a constitutional right to clean air, water, and the environment. On the federal level, the coalition believes Hochul’s move could violate the landmark Americans With Disabilities Act.

For now, though, legal eagles believe their strongest affirmative defense of the program is the original 2019 statute — which straightforwardly requires the state to undertake a congestion pricing program in Manhattan’s core.

“In 2019, the State Legislature passed a law saying that the MTA shall implement congestion pricing, notwithstanding any other provision of law,” said Michael Gerrard, an environmental law scholar and faculty director of Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. “It gave the MTA sole legal authority. Gov. Hochul does not have the power to reverse that state statute.”

Gerrard contended that Hochul likely violated the law with her announcement of the pause, notwithstanding questions of ripeness.

“Although the governor said that this was a temporary pause, indefinite pause, the courts of New York are clear that an indefinite pause is tantamount to a permanent pause,” Gerrard continued. “And we are prepared to go to court to challenge that.”

Reached for comment, Gov. Hochul’s press secretary Avi Small would not comment specifically on the potential litigation.

“Like the majority of New Yorkers, Governor Hochul believes this is not the right time to implement congestion pricing,” said Small. “We can’t comment on pending or hypothetical litigation.”

MTA Chair Janno Lieber similarly wouldn’t get into specifics on pending litigation at an unrelated press conference Wednesday, noting the agency’s current priority is to “retool, reprioritize, and shrink the capital program to deal with the money that we know we have.”

“That’s about $13 billion compared to $28.5 billion of planned capital work,” he said; earlier this week, Lieber said the agency will have to shift its focus from modernization work to projects aimed at keeping the system from “falling apart.”

Lander came to the MTA’s defense Wednesday.

“The bar for the MTA shouldn’t be ensuring the system doesn’t fall apart,” Lander said on Wednesday, who referred to Hochul’s move as a “disastrously wrong turn.”

Should Hochul not reverse herself again, Gerrard said, suits could be expected in the next few weeks.

The filing depends on a series of procedural actions, including the state Transportation Commissioner declining to sign a document giving final authorization for a “Value Pricing Pilot Program” (VPPP), which previously had been expected to be a mere formality.

Read more: Fifth Ave Prepares for Boricua Celebration