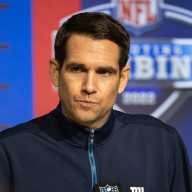

The man tasked with easing crowding and wait times in the city’s subway is rolling up his sleeves.

Transit executive Pete Tomlin, whom the MTA hired in early December, is one week into his new job overseeing New York City Transit’s ambitious plan to replace much of the subway’s century-old signal system — the traffic lights for trains — with a modern equivalent.

“I can’t think of a bigger, more exciting, more difficult job,” said Tomlin in the No. 7 line’s Hudson Yards-34th Street station on Monday.

The overhaul would automate the operation of trains with a computerized system known as Communications-Based Train Control, in theory allowing the MTA to run more trains more closely together and eliminate some of the failure-prone elements of its current signal system that can cause delays. That could potentially allow for more trains, shorter waits and more reliable service.

Tomlin, the MTA’s modern signaling chief, is working under NYC Transit President Andy Byford and his still-unfunded, roughly $40 billion Fast Forward plan, which hinges on modernizing the signals along much of the track over a decade during full night and weekend outages. In the first five years, a new signal system would be installed on enough of the track so that 3 million daily riders are impacted — a majority of commuters.

There are three big areas of concern for Tomlin, he says: the 24/7 subway system, which limits track access for upgrades; the sheer size of the system, which is the largest in terms of number of stations; and the fact that, unlike elsewhere, different train car models can run on different lines. That complicates an already difficult task.

“A colleague of mine once described it like … conducting open-heart surgery on a 100-year-old person while he’s eating his lunch,” said Tomlin. “It’s a fine art.”

The MTA has struggled with the art form. It has installed CBTC on only two lines: the L and more recently the 7, the latter of which has been riddled with service issues as the MTA works out kinks with the signal software. Operators are still driving the trains on the Queens-to-Manhattan line, and Tomlin hopes to accelerate to this March plans to automate train movement on it.

“I’ve also asked for [Tomlin] to look at things from a fresh perspective,” said Byford, who called Tomlin a “world expert” on signaling.

“There are reasons why the resignalling has taken so long in New York — some of which are valid, some of which I don’t really buy,” Byford said on Monday.

Tomlin’s arrival comes as the state hashes out its next budget by the April 1 due date, which has direct implications as to whether Fast Forward can be funded. Before then, he’ll be working to launch a pilot program this summer of newer, unproven signal tech, called ultra-wideband, and to re-evaluate the nascent CBTC projects on the Eighth Avenue, Culver and Queens Boulevard lines.

He also joins the MTA as the authority has started to acknowledge that its own mismanagement — and not necessarily just old signals — has hindered subway service.

Before Byford’s arrival in January 2018, the MTA had been incorrectly blaming riders for subway delays — lumping tens of thousands into its public records under the cause “Over Crowding / Insufficient Capacity / Other.” But that blame game withered as transit ridership dropped — how could there be more overcrowding if fewer people were riding?

Byford discovered quickly that the MTA had hundreds of faulty signal timers, which help enforce speed restrictions, that were potentially incorrectly stopping trains traveling at the correct speeds. That created a culture of distrust among train operators that slowed service and reduced capacity.

“It seems that the MTA can realize a lot of immediate capacity increases by addressing choke points and resolving these signal timer issues before the anticipation of CBTC — which isn’t to say we don’t need a modern signal system,” said blogger Ben Kabak of Second Avenue Sagas. “But the idea that we have to wait for years or decades for those capacity upgrades is probably not as accurate as people believed a few years ago.”

Tomlin has worked with Byford previously and, like his new boss, has bounced around from transit agencies across the world. He’s overseen CBTC installations in London and Hong Kong before most recently leading the ongoing effort to resignal the Toronto Transit Commission’s Line 1.

But that project looks eerily similar to the MTA’s 7 line work, which was delayed for years. The Toronto newspaper The Globe and Mail reported in late December that the TTC would miss its deadline to resignal Line 1 by the end of 2019, and would be likely to need two more years and more money to complete the work.

The MTA did not immediately respond to a request for comment on how the report relates to Tomlin’s work there.

The MTA currently staffs two workers on each train — an operator to drive and a conductor to make announcements and work the doors. While Byford said it was “unusual” to have a two-person setup, CBTC installation would not eliminate the role of an operator.

“The system is designed for an operator,” said Tomlin, who likened an operator’s role under CBTC to that of a driver when an automobile is in cruise control.

Byford is now looking to Albany to pass a congestion pricing plan in the next state budget, which Gov. Andrew Cuomo believes could raise around $1 billion in net revenue annually. That would, in part, pay for Fast Forward and the signal modernization, which Byford views as critical to improving service.

The MTA has advocacy groups in its corner.

“The 1930s-era signals just aren’t cutting it, no matter how we enhance their maintenance,” said Danny Pearlstein, spokesman for the group Riders Alliance. “It’s essential that we modernize our signal system and that the governor and legislature pass congestion pricing to pay for [it].”