In mid-August, officials from the state court system’s Office of Diversity and Inclusion (ODI) traveled to the site of a 1932 lynching in the Adirondack Mountains to memorialize the victim as part of a staff retreat.

The department conducted the trip in coordination with Alabama’s Legacy Museum, which gathers soil from sites of racial terror to raise awareness of the history of slavery and honor the memory of those who were killed. The museum engraves jars with a name if known and a date and location to display them as a kind of burial rite.

Department director Tony Walters said the trip fits with the scope of the office’s mission for staff to engage in uncomfortable and sometimes painful conversation around discrimination and oppression to improve awareness and “access to justice” in the court system.

“Diversity, equity and inclusion is an access to justice issue,” Walters said, “And we feel like this man was not allowed any justice.”

While one of ODI’s stated goals is the expanded recruitment and hiring of candidates from underrepresented backgrounds, Walters said that its emphasis gradually shifted since his start in the department in 1990s when it was called the Equal Employment Opportunity office, to focus on cultural awareness around bias and the promotion of a respectful workplace.

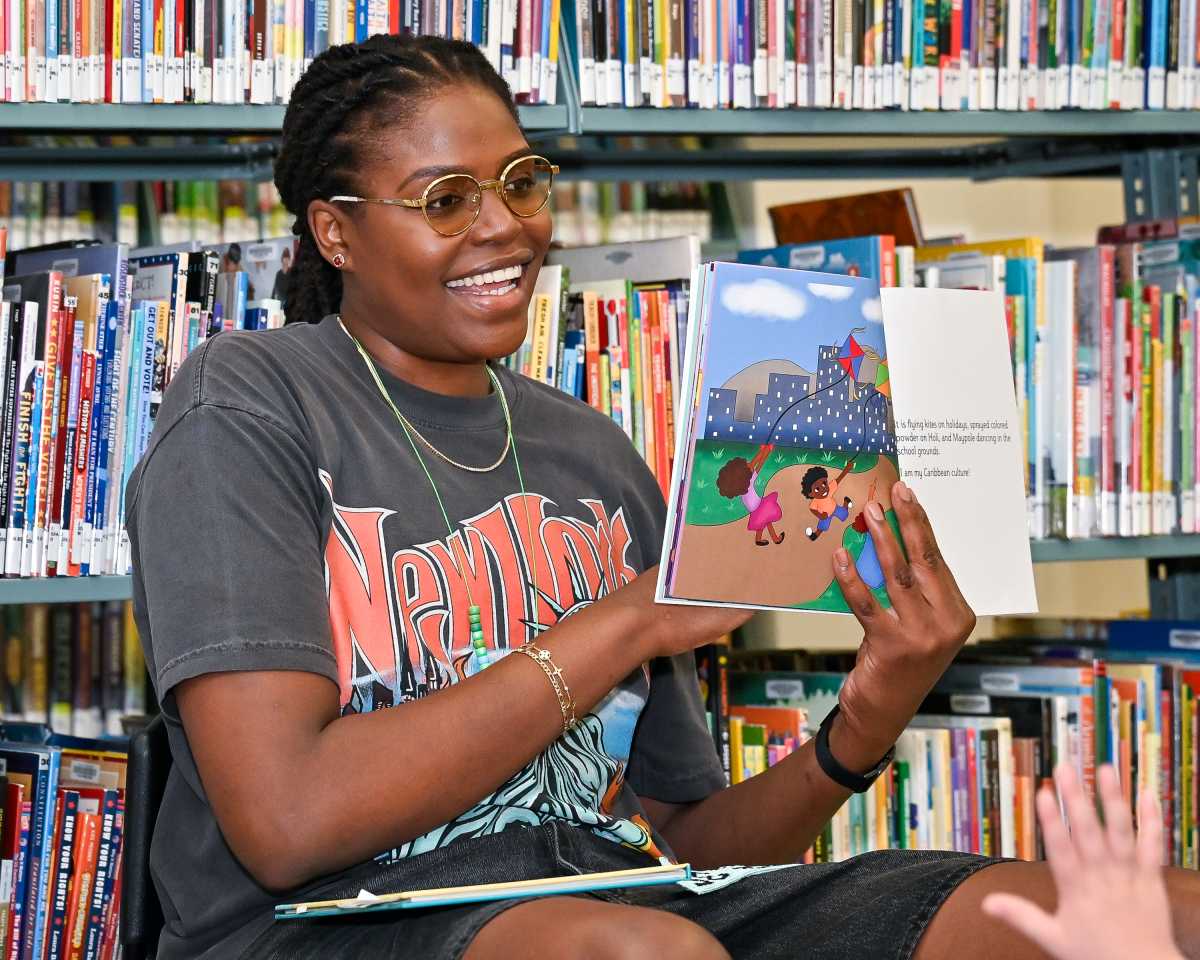

Like the Adirondack retreat, Walters said, these programs aren’t the usual sensitivity training that employees often take. One thing he’s done is to hire Nicole Hylton, a special project coordinator who holds dual master’s degrees in Pan-African studies and behavioral psychology, who he said has brought a degree of historical research to the programming.

“We’re going a little bit deeper in the weeds,” Walters said.

Last year ODI held both an “Antisemitism Today and its Roots,” program for over 1,000 court employees, followed by a program entitled “Honoring Our Shared Humanity: Understanding Islamophobia.”

Walters has found himself doing a lot of explaining over the past several years as diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) has become a buzzword for what rightwing activists frame as a form of unfair reverse discrimination.

“I think it’s very important that we are not limiting this work to an acronym because that acronym has become weaponized,” Walters said. “We are doing a lot to let people understand it’s not just an acronym, that the tenets that support that are inclusivity, fairness, respect, bias-free [and] discrimination-free environments, conversations and interactions.”

The ODI traces its roots back to 1975, a period when public entities were federally mandated to address discrimination. A state lawsuit in 1977 over exam requirements that discriminated against Black and Hispanic court officers was a key event that led to the office being “supercharged” with resources, Walters said.

Walters, who came to the court system in 1994 from an administrative job in city government and has directed the office since 2011, said the shift is the result of the dispersion of its duties to other commissions and departments.

ODI is not the only entity within the court system doing this work. The Franklin H. Williams Commission, for instance, an independent group of judges, lawyers and court administrators formed in 1988 to advocate for judicial diversity, has taken more of a role in officially pushing for more minority judges, he said. Walters added the relationship between the ODI and the commission has evolved from a sometimes antagonistic competition for influence to a more collaborative partnership, as both realized they shared similar goals.

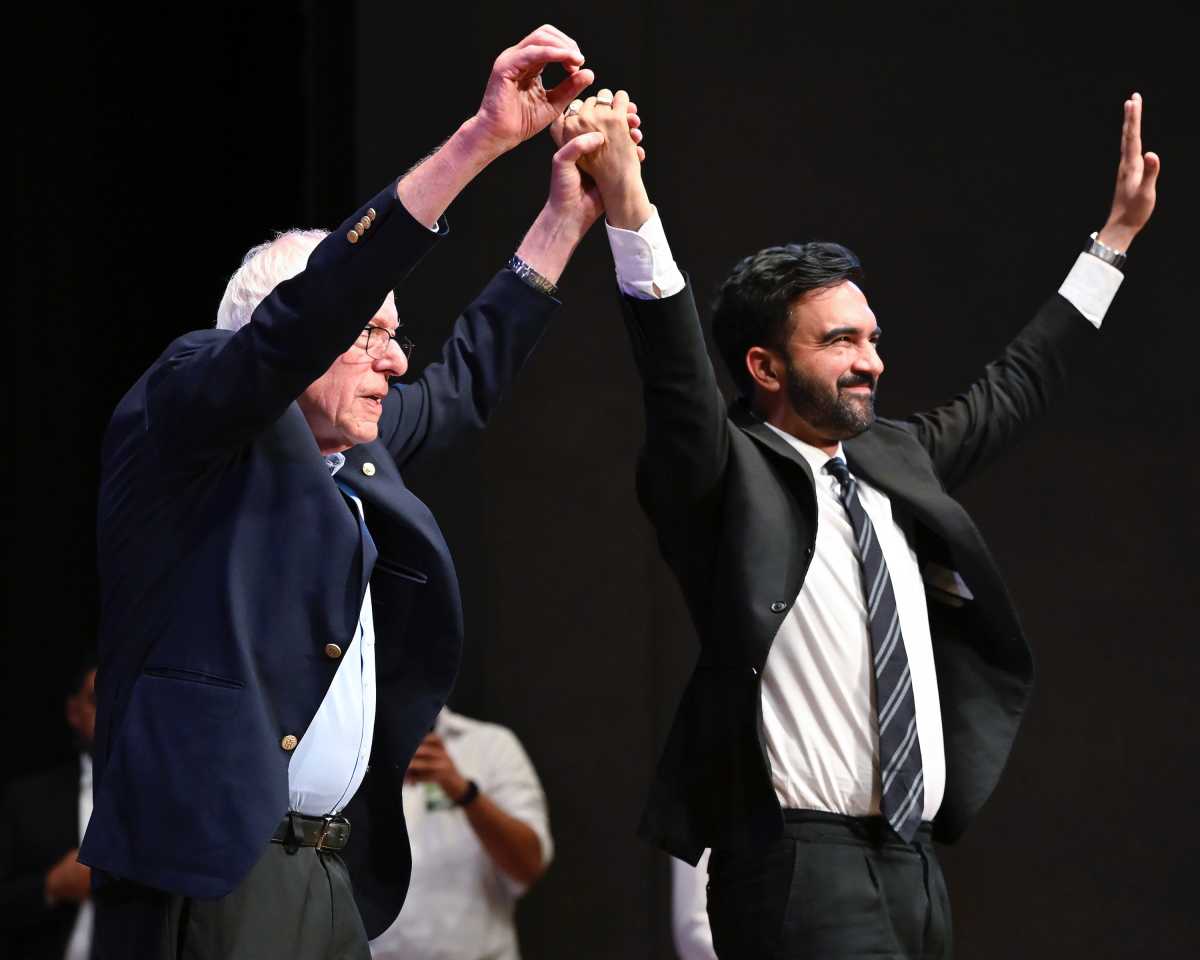

Unlike decades past where the commission would play a role in setting the course for judicial leadership, Walters said that the administration under Chief Judge Rowan Wilson has taken a more proactive role on diverse employment. The top three administrative judges, Wilson, Chief Administrative Judge Joseph Zayas and First Deputy Chief Administrative Judge Norman St. George are all people of color, which Walters said has impacted how they see diversity efforts.

“They are committed to also making sure that [in] the appointments that they make, they’re thinking about diversity, they’re thinking about all of the best qualified people,” he said. “That is the best case. It’s what you can aspire to,” Walters said.

The training and programming that ODI provides doesn’t just target administrative staff or court clerks, officers and others who interact with the public, but judges too in terms of how they handle their adjudication duties.

The office offers a wide range of training and programs, including the “Intro to Cultural Consciousness” program, which delves into topics like power, oppression, and implicit bias, aiming to help employees recognize and mitigate their own biases.

Looking to the future, however, Walters said that he wants to take these trainings even further — allowing employees to openly share and ask questions about sensitive topics without fear of judgment. He believes this is a necessary step to move the needle on diversity and inclusion, as current programs often leave many questions unasked and unanswered.

“I’ll probably get in trouble for saying this, but I’m going to say it,” Walters said. “I think a lot of this work, especially peer-to-peer, comes down to somehow creating platforms of conversation and communication. What we call sometimes awkward and difficult conversations. That’s the part that’s really not getting done.”

Meanwhile, the office’s influence has moved away from direct recruitment efforts to providing guidance and support for other entities to encourage underrepresented candidates to apply for jobs in the court system.

When Walters began working there he spearheaded an effort to recruit court officers from historically Black colleges and universities. Now in upstate regions, ODI works with a network of churches and religious groups to pass on news of new openings to underrepresented groups.

One thing that the office has continued to do is career development, Walters said. In partnership with the Williams Commission, it runs a professional development academy, which helps employees with skills like resume writing and public speaking to better prepare them for promotional exams and interviews. Forty-four percent of the participants ended up receiving promotions across the court system.

Walters noted however that formal trend studies are not always a clear way to measure progress in terms of something as qualitative as cultural consciousness.

In response to what he deemed the “summer of unrest” in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, the court system began broadcasting to staff the role of its inspector general’s office, the department in charge of complaints involving colleagues’ behavior. It resulted in a three- to four-fold increase in complaints, Walters said, indicating that more people felt empowered to report issues, but which also showed an increase in complaints in response to the reform.

“We don’t try to stray too far from what is the operational impact,” Walters said. “But the operational impact is, at least I believe, to build a better mousetrap. You need all hands on deck, all different perspectives.”

As with most government offices, Walters said, limited resources are his primary challenge. With a small team of six, the office sometimes struggles to meet the high demand for its training and programs across a system that employs over 15,000 non-judicial staff and another one-to-2,000 judges. To address this, he said the office is working to create a “trainer of trainers” model, empowering local employees to facilitate these cultural awareness sessions.

“I would love to have double the size of staff, “ he said. “We would have somebody training in this type of work somewhere in the state, probably at least once a week.”