Faith Ringgold did not simply paint history—she broke it open. She reached into the marrow of America’s most violent foundations, pulled forth the bones, and demanded that we look.

Her Slave Rape Series—raw, spiritual, brutal, and incandescent—remains one of the most courageous achievements in American art, a portal through which the full seismic force of her career becomes legible. Through these paintings, she forged a new language for Black womanhood, a new architecture for Black truth, and an entirely new horizon for artistic liberation.

Jack Shainman Gallery’s inaugural exhibition dedicated to her is therefore far more than a show; it is testimony, ceremony, and reckoning. It wraps history in cloth and color with a conviction so potent that it refuses passive viewing. This is an experience that cracks open the conscience, demands a deep recalibration of how we understand art’s capacity to confront and transform, and ultimately leaves you with the unmistakable realization that Ringgold’s work is not merely to be admired but to be witnessed, absorbed, and revered.

Created in 1973, the Slave Rape paintings were an audacious intervention into both American history and the art-historical canon. Ringgold inserted herself—and her daughters—into the bodies of enslaved women, collapsing time, identity, and memory into a single harrowing tableau. This was not a reenactment nor a spectacle; this was reclamation with surgical clarity. She refused to let the past remain a distant, anonymous nightmare. She insisted on its proximity and its living consequences.

By harnessing her own likeness, she shattered the convenient emotional distance that had long allowed the nation to romanticize the plantation and sanitize its atrocities. In doing so, she revealed that the Black female body, dismissed by history and ignored by institutions, is in fact one of the central pillars of American cultural consciousness. Her choice to embody these women was both a testament and a defiance, a declaration that the very site of attempted erasure could become a site of radical authorship.

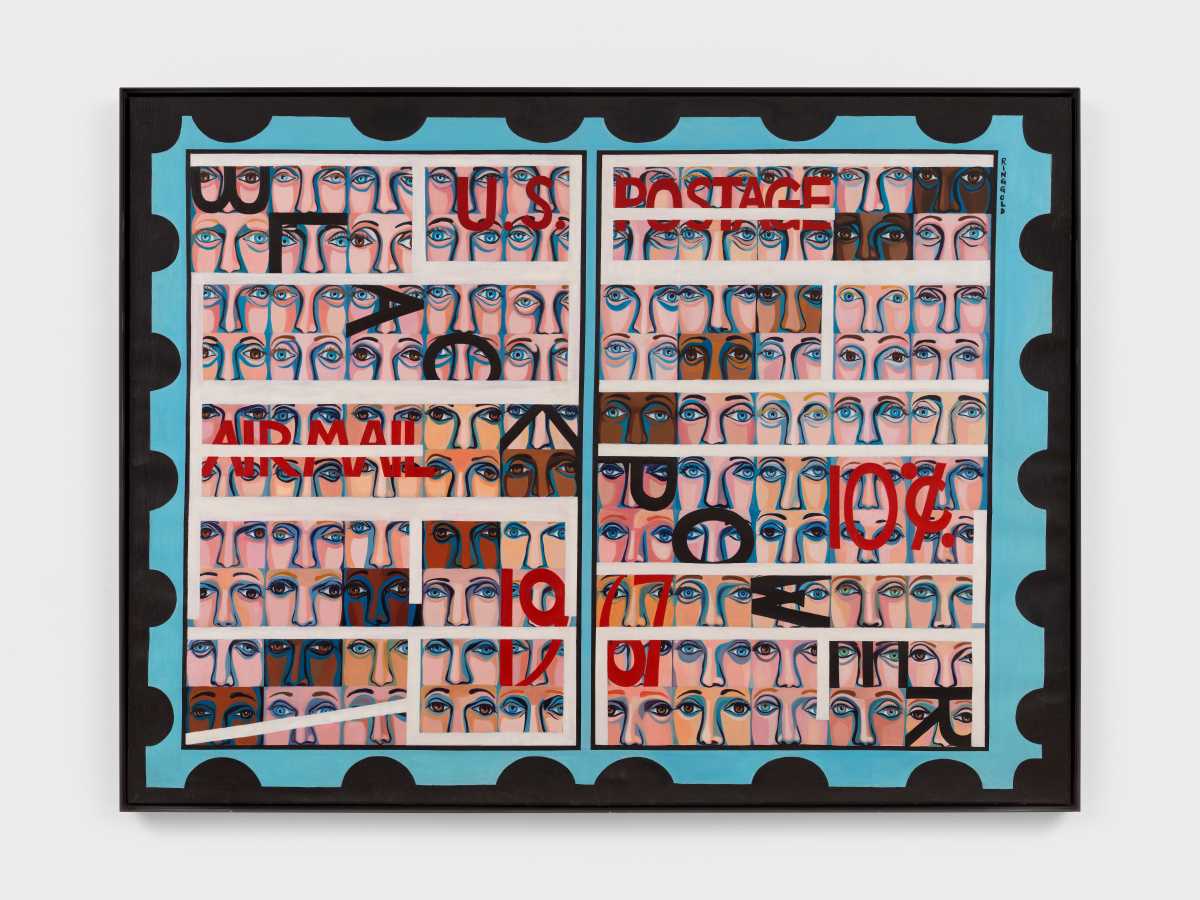

Ringgold’s oeuvre expanded with the elegance of a mind unwilling to be contained. Her early Harlem paintings of the 1960s and 70s already displayed a sophistication that belied the limited opportunities afforded to Black women artists of the period. Her figures were carved in unapologetic contours; her spatial constructions unraveled the Eurocentric logic that dominated the academy; her palette carried the tonal weight of lived experience rather than decorative whimsy.

These works form the scaffolding from which her later innovations would rise, and the exhibition positions them with admirable intelligence, allowing the viewer to watch her sharpen her voice against the frictions of her era.

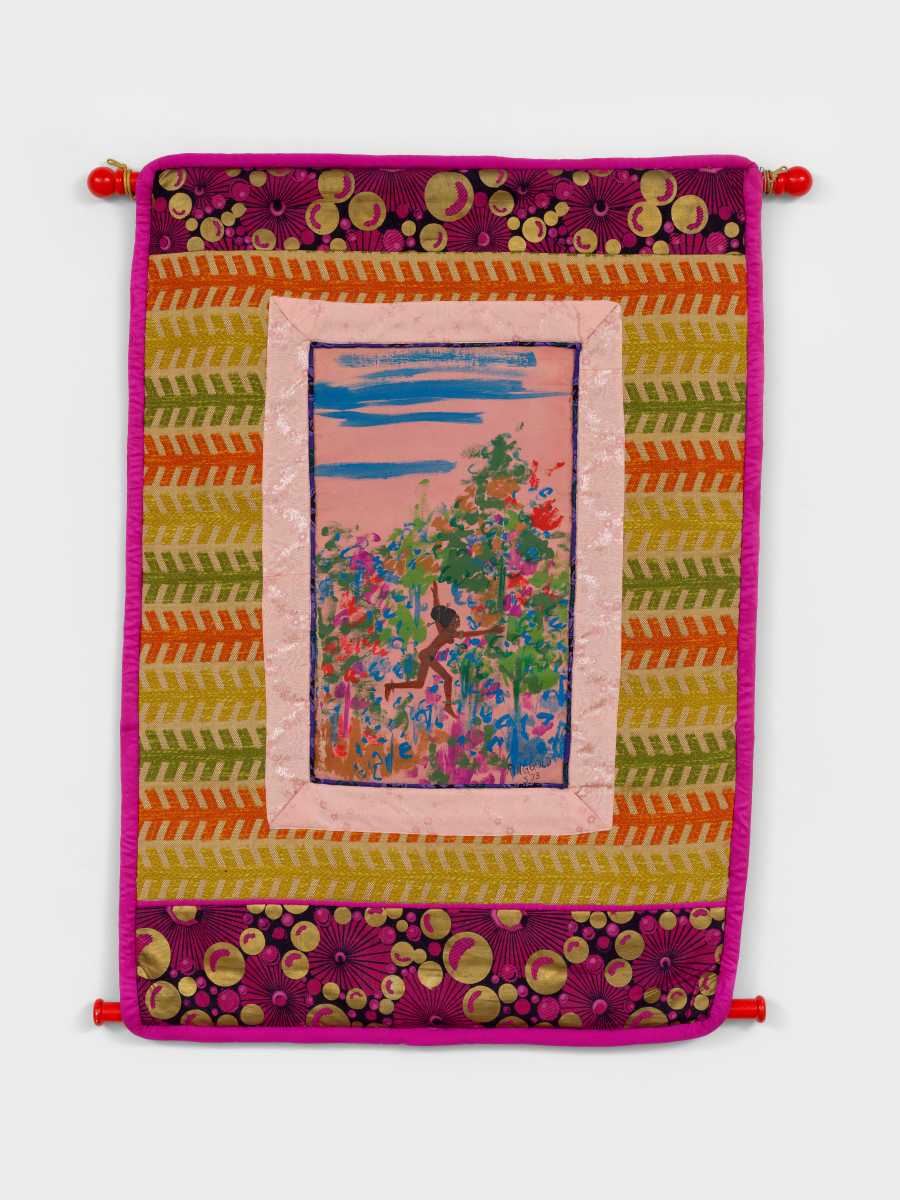

The introduction of the tankas in the 1970s marked a decisive transformation in Ringgold’s artistic vocabulary. Inspired by Tibetan thangkas encountered at the Rijksmuseum, she adopted and reimagined the form with astonishing dexterity. Her version—paintings edged with sewn fabric borders—became a medium through which she fused African aesthetic lineages, Black American textile traditions, and the compositional rigor of European painting.

These tankas are portals: they glide between continents, histories, and spiritual registers with a grace that belies their conceptual audacity. They also demonstrate Ringgold’s strategic brilliance. The portability of these works allowed her to circumvent the economic and institutional barriers imposed on women artists, making her own mobility a political and artistic act.

Her textile experiments expanded further into soft sculpture and performance. Works like The Atlanta Children—made in grief and righteous fury after the murders of 28 Black children—elevate fabric to a vessel of mourning, resistance, and tenderness. These pieces stand as reminders that Ringgold never separated the aesthetic from the ethical; every gesture is infused with responsibility, every material choice with intent.

Her performance masks and painted costumes underscore her profound understanding of African diasporic traditions and theatre, revealing an artist who saw storytelling as a multi-dimensional instrument of power.

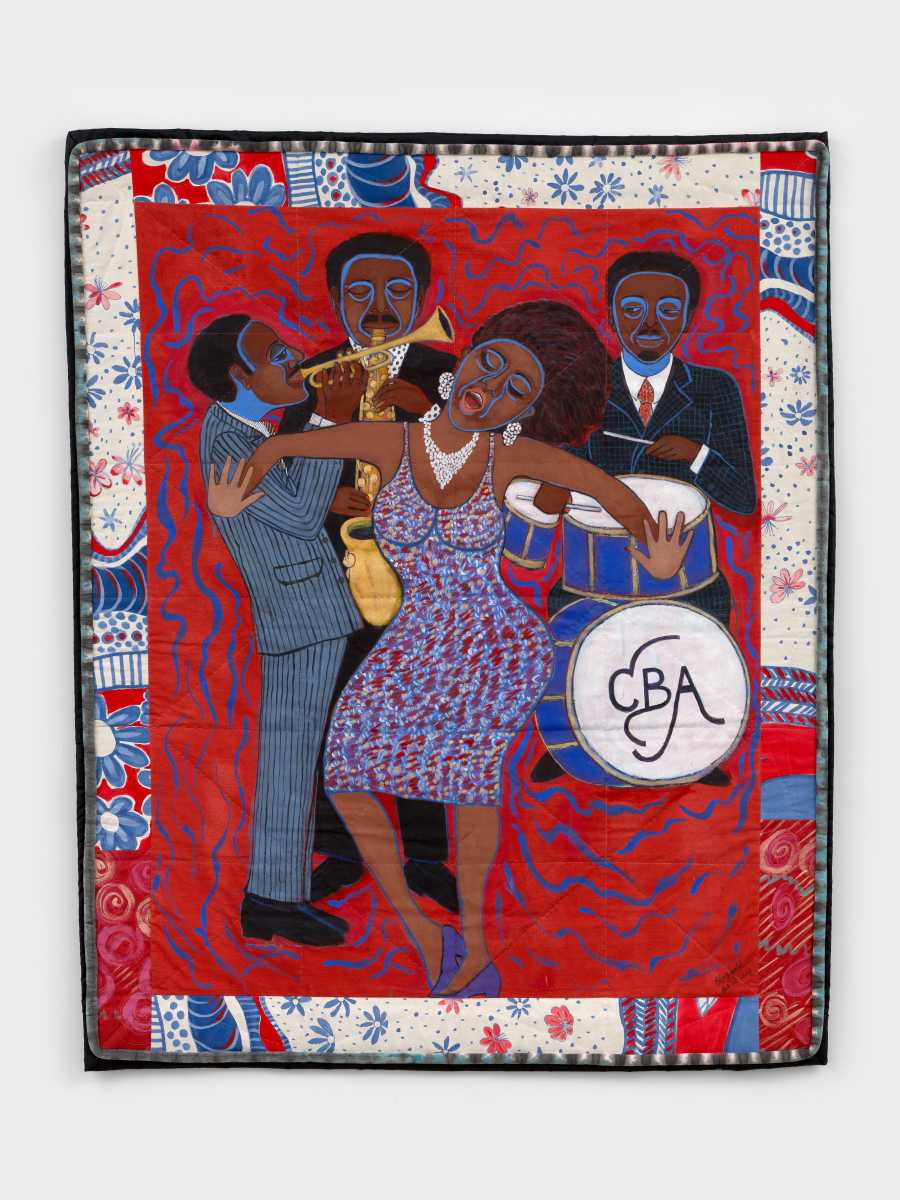

Ringgold’s story quilts, perhaps her most celebrated contributions, reveal the full force of her narrative genius. They are monuments disguised as domestic objects, intimate yet monumental, scholarly yet emotionally lush. She wove autobiography, communal memory, diasporic history, and feminine lineage into compositions that defy categorization. These quilts do not merely tell stories; they preserve them.

They operate as living archives for voices excluded from textbooks, from museum walls, and from polite conversation. Their intelligence is matched only by their beauty. Through them, Ringgold transforms cloth into a site of scholarship, imagination, and liberation.

Jack Shainman and his curatorial team seem to understand the clarity and strength the full body of her work demands. Her early paintings thrum with political electricity; her tankas stretch the definition of painting itself; her soft sculptures unmask the nation’s wounded conscience; her story quilts envelop viewers in entire cosmologies of Black American life. The installation resists sensationalism and instead allows the complexity of her ideas to speak in their full register.

Her practice emerges not as a series of stylistic evolutions but as a coherent intellectual mission: to restore humanity where it was stolen, to elevate craft where it was dismissed, and to reorient American art around the voices it tried to expunge.

Unique in its approach–this exhibition is not merely a survey of a remarkable career. It is a confrontation with the moral and aesthetic failures of the past and a vision of what art can become when guided by fearlessness, precision, and spiritual intelligence. Ringgold’s work is a testament to the alchemy of turning violation into vision, inherited pain into cultural power, and historical fracture into pathways of renewed possibility. Her practice does not linger in wounds; it transforms them into portals, widening from cracks to windows to doors to entire universes.