Planning to convert a barely used railroad right-of-way running from the Bay Ridge waterfront through Brooklyn to Jackson Heights, Queens for passenger light rail, known as the IBX, is well underway.

Now is the time to figure out how to make sure it actually gets built and how to make the most of it for housing and economic development.

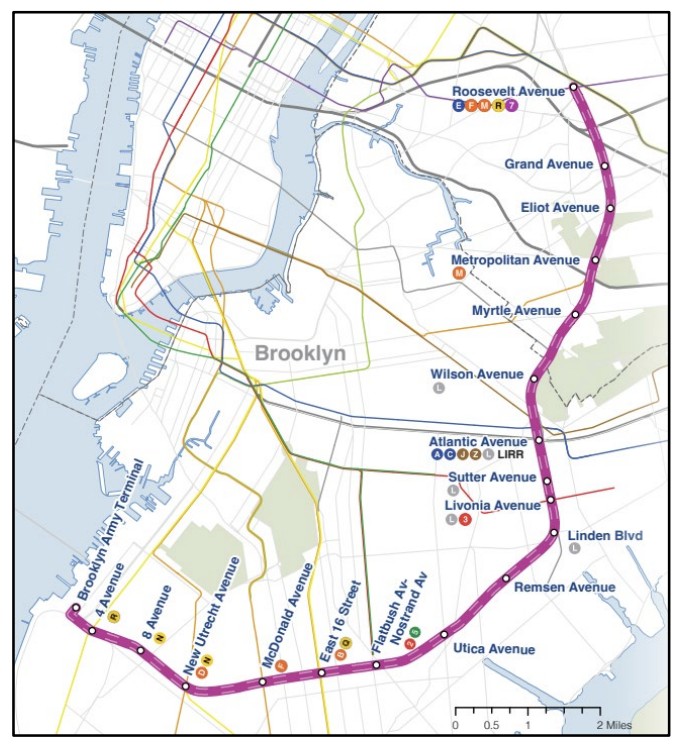

The 14-mile Interboro Express would provide new transit options for almost a million New Yorkers who live along the route, along with about a quarter million commuters who work in Brooklyn and Queens. Taking only 40 minutes from end to end, it would connect with 17 existing subway stations and the Long Island Railroad.

But the IBX is more than a transit project. It’s a chance to rethink land use and economic development in parts of Brooklyn and Queens that can help meet the desperate shortage of housing.

Neighborhoods like East Flatbush, Brownsville, and Maspeth lack transit access that attracts residents and jobs. The IBX could change that — if we’re able to position them for growth.

Proposed by the Regional Plan Association and championed by Governor Kathy Hochul, the IBX is one of the biggest proposed transit expansions since the Second Avenue subway was conceived. But we can’t wait a hundred years for it to be built like that took.

New York City development has long been shaped by transit expansion.

When the original IRT line opened in 1904, it spurred residential and commercial development on the Upper West Side and in the Bronx, as did the expansion of the IRT and BMT lines into Brooklyn and Queens. Neighborhoods like Crown Heights, Jackson Heights, and Forest Hills were built around new stations, with investment following the tracks.

The IND lines, built in the 1930s, continued this pattern, supporting housing and commercial corridors in places like Washington Heights and central Brooklyn. In each case, transit access made higher-density development desirable — and viable.

Neighborhoods without mass transit? Not so much.

Now there is the rare new opportunity to update that model for the 21st century. Unlike the early subway expansions, which often involved public-private coordination and planning, today’s fragmented governance makes it harder to align transit investment with development.

If we want the IBX to be more than a line on a map, we need to start planning now — not just for tracks and stations, but for the communities that should grow around them. That means bold action on land use, creative financing, and a commitment to equitable development — and a recognition that transit investment must be matched with financing tools that let the MTA share in the value it creates.

According to a recent report by the New York Building Congress, more than 70,000 new homes could be built within a half-mile of the proposed IBX stations — and potentially over 100,000 units over the next decade — if land use rule changes are enacted. They found that nearly half the land is zoned for low-density residential use, while only a third is zoned for higher-density. To unlock the corridor’s full potential, the Building Congress recommends targeted upzoning — especially around stations like Eliot Avenue, Grand Avenue, Metropolitan Avenue, and Utica Avenue.

Doing this with station by station rezonings runs the risk of local opposition derailment

The Department of City Planning could pursue an area-wide rezoning to implement these recommendations, putting final approval with the entire City Council and the Mayor. That would be a step in the right direction — but it’s not enough. While DCP has the authority to change zoning, it does not have the ability to capture and redirect the increased property tax revenue that results from new development. That means the MTA would see no direct financial benefit from the value it helps create — even as it shoulders the cost of building and operating the IBX.

The MTA has just awarded a $166 million design contract, with funding for about half the $5.5 billion cost accounted for in the MTA capital plan. But with congestion pricing still controversial and looming uncertainty about the availability of federal support, the project’s funding for construction and cars is far from guaranteed.

That’s where the state comes in. A General Project Plan developed by Empire State Development (ESD) could supersede local zoning and more importantly, take nominal title to development sites, exempting them from city property taxes and structure payments-in-lieu-of-taxes (PILOTs) that allow developers to share that revenue with the MTA, as well as with the city for .new schools, fire houses, libraries and the like.

This model has precedent. The 7 train extension to Hudson Yards was financed through tax increment financing, with future property tax revenues used to repay bonds issued for the project. More recently, ESD created a PILOT-based program for developers in Gowanus who missed the window for 421-a property tax abatements which would have let their projects to move forward had the state legislature not extended the deadline.

This is not to say that local communities and elected officials should be cut out of the process. To the contrary, their input will be critical to identifying local needs. But we can do better than business as usual. ESD can form a subsidiary with City Hall, Borough Hall and local representation, similar to the overall governance of Brooklyn Bridge Park.

Let’s put the IBX on the fast track.

Former NYC Council Member Ken Fisher is an attorney with the national law firm of Cozen O’Connor. His practice concentrates on city and state approvals, transactions, regulations and investigations. The views expressed are his own.