As the famed New York-based real estate law firm Kramer Levin is approaching a merger with a prominent international firm, forming one of the largest 20 global law firms, its land use attorneys are reflecting on their footprint in the Big Apple.

Kramer Levin’s land use co-chair Elise Wagner said that when she first heard about the merger with Australia and UK-based Herbert Smith Freehills, she was apprehensive because of how specific New York land use law is.

What Wagner and her co-chair James Power say set Kramer Levin’s land use practice apart is how it has pioneered an approach where its attorneys act just as much as planners and advisers as litigators.

“You’re not just being a lawyer. You’re being a planner and dealing with environmental issues, political strategy, and working with government officials,” Wagner said. “There’s always a problem to solve and always the pleasure and the satisfaction of saying ‘I helped make this happen.’”

At a firm that has advised on everything from skyline-defining skyscrapers to neighborhood-wide rezonings, the firm’s reach is as broad as its land use functions.

“We, as a collective department, have been involved in basically every major development project in New York City, either on the borrower or the lender side, or the investor side, tenant side,” Power said. “And we have such a long institutional memory in terms of how projects have been approved, what it takes to get from A to B and how to build in New York City.”

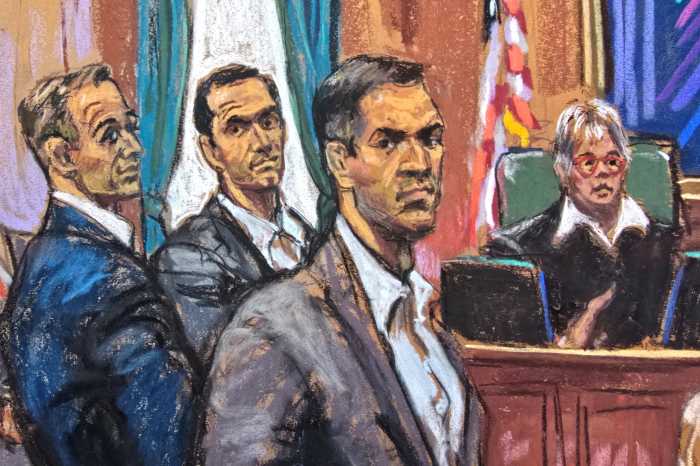

Given how New York City’s land use process works, the role Kramer Levin plays means being embedded in local politics and government — a position that goes back to its roots in two notable firms, led by two civic and legal giants; John Zuccotti of Tufo & Zuccotti and Sandy Lindenbaum of Rosenman & Colin. Wagner and Power, respectively, learned the ropes under these two real estate titans.

Though Zuccotti is perhaps best known for the expansive Lower Manhattan park that bears his name, his early career was defined by his law practice and civil service. He served on the city’s planning commission in 1971; and was its chairman from 1973 to 1975. He later served in Mayor Ed Koch’s administration.

Wagner said Zuccoti “was a person who really knew how to bring people together and also understood the important relationship between government and the private sector in the life of the city and the regeneration of the city as it happens from generation to generation.”

Lindenbaum, on the other hand, known as the “dean” of New York land use lawyers, made a reputation in the real estate law community for cultivating a deep knowledge of the city’s 1961 zoning resolution, which split the city up in zoning districts.

Both men established new standards within land use in the city when they started to hire planners at the law firm who had experience within the Department of City Planning. Today, land use attorneys like Power and Wagner function as planning and development consultants as well as litigants who work closely with city government officials.

“You work together and you respect each other and you explain why what your client wants to do is not only good for the clients, but good for the city and good for the neighborhood,” Wagner said.

The more traditional part of what the firm does involves technical assistance in the process of acquiring capital for developers to launch projects. The firm’s multidisciplinary approach really shines through when it comes to working with developers who are proposing neighborhood-wide rezonings — a long, heavily regulated process that can spark fierce community resistance and complicated political jockeying.

“We’re the ones who really apply the zoning to the development site,” Power said. “So we’re often in a position of identifying laws and problems with legislation that we can then testify at public hearings about, or present the city planning in other ways to try to clean it up.”

For instance, for 10 years Wagner has been working with Plaxall, a plastics manufacturing company and real estate developer that owns 12 acres in Long Island City, where Amazon planned to build part of its HQ2 in 2019, before the e-commerce giant dramatically killed the project amid strong opposition from local organizers and politicians.

Wagner’s role was negotiating with the city and the state on the agreements for “what would’ve been an amazing project to happen.” When Long Island City was selected as the potential area for the development, Wagner was heavily involved in negotiations for Plaxall, which had the largest piece of property in the area.

“One of the flaws of that endeavor was there wasn’t that much community outreach, right?” Wagner said. “It was something where there were decisions made at the government level that this is something that was going to happen and it was going to happen quickly… but the fact there was not a lot of community outreach caused its demise because it left the door open for these public officials to oppose the project and for it to fall apart.”

And just like Lindenbaum who built his name mastering the city’s mid-century rezoning changes, both Wagner and Power continue to adapt as the city’s zoning law goes through dramatic evolutions. In the past two years alone, the city has seen arguably the most comprehensive overhaul of zoning resolution since adopted in 1961 in the City of Yes zoning reform and the overhaul of the section of state tax law that played a key role in incentivizing developers to build new affordable housing in exchange for property tax exemption.

“[City of Yes] has really required us to go back on almost every single project and reevaluate what the implications are for those projects except for the ones that are vested under the old zoning,” Power said.

Wagner added that when she first started practicing, tax law was completely out of the realm of land use, but the city’s structure for incentivizing affordable housing has completely changed that.

“All of those wonderful rezonings are terrific, but if the taxes don’t work and you can’t finance a project… it’s a problem,” Wagner said.

She added that 485-x, the tax law that Governor Hochul and the state legislature replaced 421-a with, has been stalling construction because in her view it sets the bar too high for union construction wages.

Both Wagner and Power said that they pursued a career in land use out of a sense of civic duty.

“I grew up in the Bronx and really saw a lot of changes in my neighborhood… and the city in general as I was growing up. I developed a sense that I wanted to be part of what was happening in the city and part of making New York City a better, more prosperous place,” Power said.

Wagner grew up in the suburbs, but both her parents were New Yorkers. Her interest was sparked when she got placed in an internship at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development during college.

She’s come around to the merger from a land use perspective on the ground that it will allow the firm to continue to expand on its legacy in the New York real estate market.

“I think it’s only going to make us stronger, and certainly if they have clients who are building in New York, we’ll be here to serve them,” Wagner said. “But I think it’s certainly very much accretive to our practice.”