The power of the political image comes to the New-York Historical Society with its new exhibition “Art as Activism: Graphic Art from the Merrill C. Berman Collection,” opening Friday.

The Great Depression, the civil rights movement of the ’60s and Vietnam War protests are among the subjects visitors will find covered by more than 70 works that invite new reflections on 20th century history, particularly through the turbulent lens of today.

The first of three galleries focuses on ’30s and ’40s America, where visitors will find workers’ rally posters alongside striking works by Hungarian immigrant Hugo Gellert, for communist newspaper The Daily Worker.

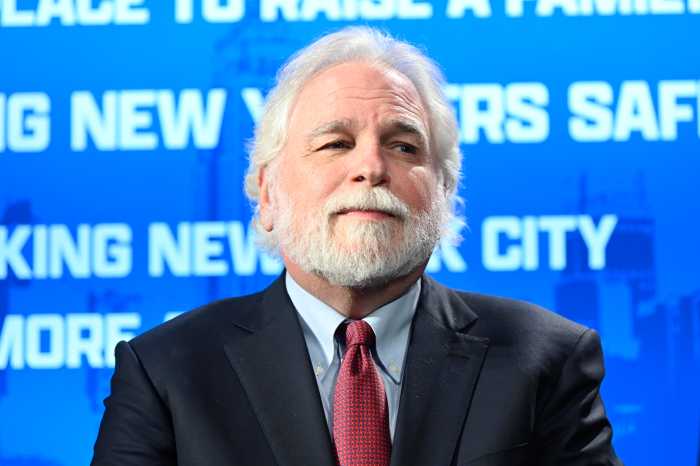

“This kind of art has to appeal to someone walking by, it has to grab you,” Stephen Edidin, chief curator at the Society, told amNewYork.

Also by Gellert is a poster for a victory rally at Yankee Stadium in 1943. Such works prompt visitors to imagine a less considered side to the history of New York City during World War II. Fifty-thousand people attended the May Day rally, where Mayor Fiorello La Guardia encouraged workers to put aside political differences for the sake of the war.

The center gallery is dedicated to the Black Panther movement of the ’60s and ’70s. The Panthers used the psychology of advertising, as well as celebrity culture, to reach their audience. Emory Douglas, who became the minister of culture of the Panthers, is a key example.

“[He] went to technical art schools where they were taught for careers in advertising and graphics, so they had that idea built in, that idea of how to project,” Edidin said.

The third and final gallery features a variety of Vietnam War protest imagery, most developed at universities such as Berkeley and Columbia, and inspired by traditional artists, like Francisco Goya.

“Red Power” posters developed by the American Indian Movement demonstrate the effectiveness of pop-inspired protest art; work by iconic pop artist James Rosenquist is also displayed. “We hope that historically it’s interesting to see the imagery and the power it had,” Edidin said. “People should think about today and that period and make their own parallels and differences.”