By Sara Levin

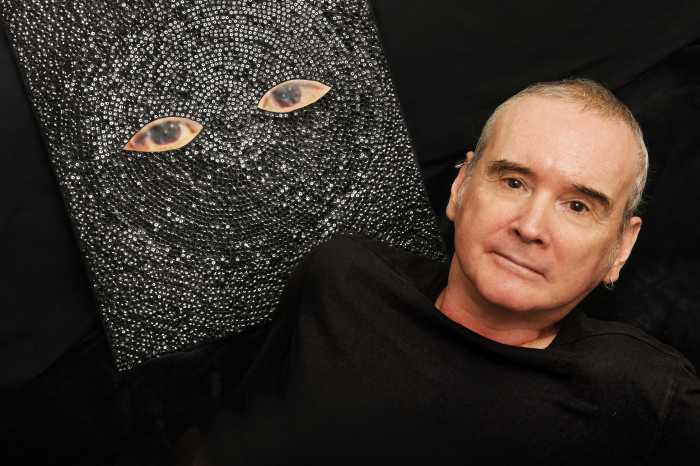

Dressed in all black, Reggie Wilson’s Fist & Heel Performance Group sadly rolls across the floor to begin its latest, full-length performance, “The Tale: Npinpee Nckutchie and the Tail of Golden Dek.” But like each word of its title — which Wilson insists means nothing — the following succession of scenes is unexpected.

Swing music quickly takes over and the dancers are brightly lit center stage, energetically slapping each other’s behinds and flailing arms to the Charleston. Then a rap beat charges in and Wilson joins the fray, convulsing his body in African-based thrusts, as if getting ready to fight.

Emblematic of the show’s breadth of varied styles, quick, corporeal transitions string together Wilson’s many interpretations of African American social dancing. In this way, the performance is full of welcome surprises. With so much in flux, the one defining characteristic of the show may be that it is impossible to connect so many different dances by anything but variation.

Wilson, who is known for seeking inspiration from all over the African Diaspora, uses African American social dances to investigate his own heritage. He was inspired to form a full-length piece based on the subject after discovering “Stepping,” a slow, soulful line dance that Wilson stumbled upon while partying in his hometown of Milwaukee.

“I go to places like Cameroon, where you figure you’re going to see something you don’t expect,” Wilson, said. “But it was R & B, and they had used it differently in my own backyard!”

Musical taste is Wilson’s most outstanding strength. Although many modern dancers are afraid that catchy tunes will overshadow movement, Wilson’s score ranges from Motown to Dance Hall to Grace Jones. And they do not overshadow it — they make the performance fun.

Best of all, Wilson is joined by several folk singers who belt earth-shaking, Southern soul. The singers are almost always on stage, and very often join in moving to recorded music. In one spectacular scene, the singers, joined by Wilson’s own powerful vocals, separate themselves from the dancers and start creating their own melodies and percussions.

In return, the dancers act out bluesy slave songs in honest yearning. In this instance, Wilson succeeds in showing the inseparable relationship between so much African-influenced dance and the music that inspires it. Unlike too many modern dancers, Wilson is unafraid to revere music.

Unfortunately, such a charged exploration of social steps and, according to Wilson, sexual innuendos, might seem slow at times when the dancers get lost in detail. These are times when the audience feels excluded.

In one instance, several members stand backwards at the front of the stage, gyrating hips to Dance Hall as if they are in a regular club. In other moments, the dancers rarely look at the audience and often become engrossed in very simple-looking movements.

Perhaps this is the risk Wilson takes in striving to adapt communal dancing to the stage. It is a noble task, because the dances he chooses might not be contemplated the same way in their normal setting. But striving to cultivate them slightly more for the viewer’s sake might be worth the contrived effort. The audience needs to be allowed more of an exciting perspective, not just that of an onlooker.

The parts that work best are when Wilson combines repetitive social steps with dynamic modern influenced jumps and hops. During one Stepping routine, the four dancers break out of a pattern and slice their arms through the air in irregular jerks, breaking up the monotony of the soulful line dance.

In the end, the performance is chock full of so much different music, dance and emotions, that it’s hard to remember or even care what Wilson’s intent was in the beginning. Perhaps he simply wants the audience to get swept up in the excitement he found going out on a Saturday night and finding something unexpected.