BY STEPHANIE BUHMANN | (stephaniebuhmann.com) | ERNEST COLE: PHOTOGRAPHER Born in 1940, Ernest Cole was one of South Africa’s first black photojournalists. In 1958, when working as a darkroom assistant at DRUM magazine in Johannesburg, he began to acquaint other young black journalists, photographers, jazz musicians and political leaders in the burgeoning anti-apartheid movement. After becoming increasingly radicalized in his political views, he started working on a book that would communicate to the rest of the world the corrosive effects of South Africa’s apartheid system.

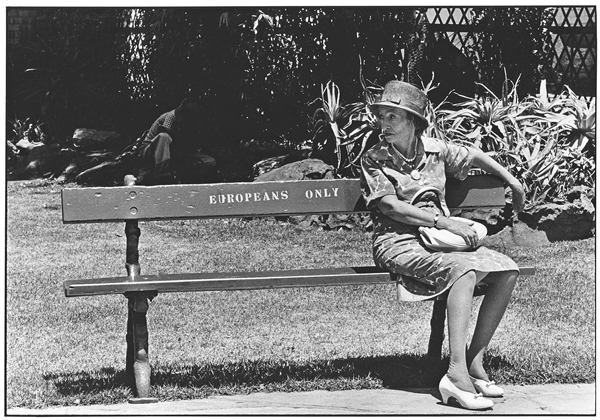

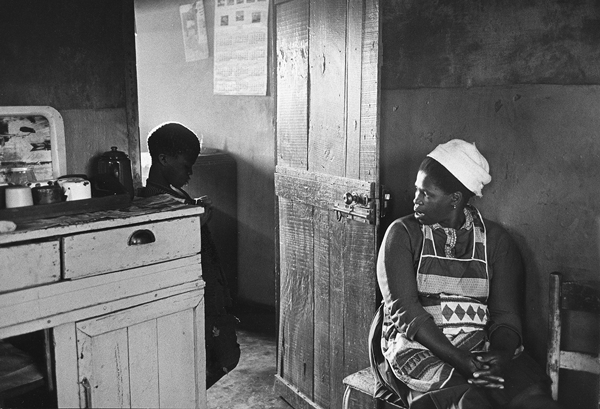

In 1966, a year before said book with the title “House of Bondage” was published, Cole was forced out of South Africa for good. The images he captured before his exile — many of which will be on display — compassionately depict the lives of black people as they negotiated apartheid’s racist laws and oppression. Migrant mineworkers waiting to be discharged from labor, parks and benches for “Europeans Only,” young men arrested and handcuffed for entering cities without their passes, and crowds crammed into claustrophobic commuter trains are just some of the scenes that Cole focused on. While the cruel realities of segregation, destitution and violence weave through many of these moving images, others depict lighter, intimate moments between mothers and children, couples and friends.

This exhibition will feature more than 100 rare black-and-white gelatin silver prints, accompanied by captions from “House of Bondage.” Organized by the Hasselblad Foundation in Gothenburg, Sweden, which holds Cole’s stunning archive, this marks the first major solo museum show of Cole’s work. It is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue.

Through Dec. 6. Reception: Mon., Sept. 8, 6–8 p.m. At Grey Art Gallery (100 Washington Square East, btw. Waverly & Washington Places). Hours: Tues./Thurs. Fri. from 11 a.m.–6 p.m. | Wed., 11 a.m.–8 p.m. | Sat., 11 a.m.–5 p.m. Call 212-998-6780 or visit nuy.edu/greyart.