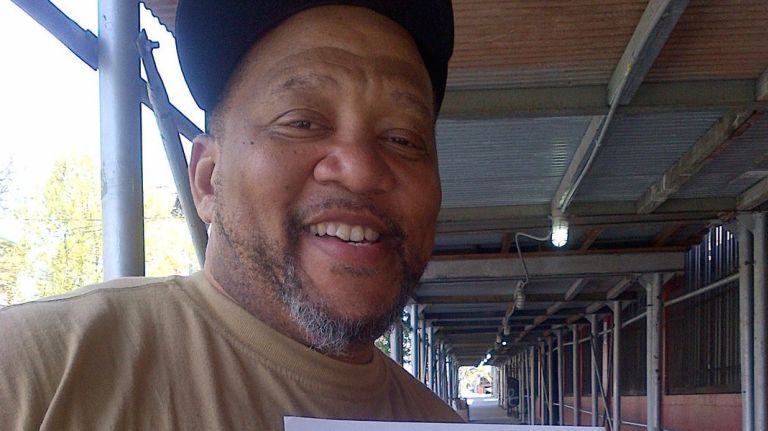

NYC is a metamorphosed marvel for Charles Lee Torian, 51, who served 15 years of a 25-year prison stint before President Barack Obama commuted his sentence, along with those of 94 other federal prisoners, in December.

“It’s a culture shock right now,” said Torian, who was arrested in Virginia with “78.6 grams of cocaine” in 2001 and convicted of conspiracy and possession with intent to distribute. On February 4, he was released to a Bronx halfway house and now lives with his wife in their one-bedroom apartment near Yankee Stadium under “home confinement” supervision.

As of March 30, Obama has commuted the sentences of 248 people — more than one-third of whom were serving life sentences — to show mercy to victims of “outdated and unduly harsh sentencing laws,” according to Whitehouse.gov.

Obama has conferred more commutations than the previous six presidents combined, and most of the reprieves were awarded to people serving mandatory decades-long sentences on drug charges. Reformers have long complained that such sentences are draconian, ineffective, costly for taxpayers, frustrating for judges, and overdue for overhaul.

Of the federal prisoners to have had their sentences commuted by the president, Torian “is the only one we’re aware of to come to Southern New York,” said Jim Blackford, senior deputy chief for the U.S. Probation Department for the Southern District, which covers Manhattan and the Bronx in NYC.

The city to which Torian returned is “a different world!” Torian exclaimed: Subways no longer accept tokens and a ride has soared from $1.50 to $2.75. The way passengers shove and push each other on the now shockingly crowded trains would never be tolerated in the big house. “There’s a higher respect level,” for personal space and other people in prison, Torian noted primly.

Torian’s new New York lacks abandoned buildings, the once omnipresent visible drug dealing and groups of people gathered on the corners smoking and drinking. Instead, “everyone is on their phone!” exclaimed Torian, who emerged from prison digitally naive: He has learned the hard way that downloading tantalizing free “apps” may infect his perplexing communication device with a disabling virus.

While other New Yorkers bemoan gentrification, Torian enjoys how much cleaner, safer and more prosperous New York appears in 2016 and says housing challenges are nothing compared to sharing a cell.

He likes its new laws, too: NYC’s Fair Chance Act, enacted in October, bans employers from asking about an applicant’s criminal record until after a conditional job offer has been made – legislation, he says, that is profoundly helpful to those who have been incarcerated. “There’s so many programs!” now to help ex-offenders, said Torian, who recently completed a Training to Work program at the Osborne Association.

Torian had been jailed before his most recent incarceration and figured that once he had a record, he had few alternatives to a life of crime. “It was real difficult for an ex-offender back then to get a job,” he recalled. Now that ex-offenders have more civil rights, “the market is more open. I get emails all day long about jobs.”

Torian grew up in the South Bronx, attending P.S. 126 and Roberto Clemente Jr. High School 166. “I wasn’t doing well in school and hated math with a passion,” so he dropped out of William Howard Taft High School at age 16, drifting into street life. “All of us smoked cigarettes, all of us smoked weed,” and drug dealing followed, as did drug arrests and a grand larceny charge.

But in prison, while earning his GED, Torian discovered he loved math. “I got really good at formulas — algebra and geometry. Now I can sit down and do square roots. I love solving problems.”

He also earned a Culinary Arts certificate and a college degree, working all the while as a cook, clerk and warehouse worker at the Beaumont Medium Federal Prison in Texas.

He had plenty of time to improve himself: His wife and three daughters couldn’t afford to visit him in Texas and his mother and sister died during his incarceration.

He has six grandchildren living down south he hopes to meet for the first time this summer.

The Osborne Association helped Torian land a job as a tour boat prep cook that begins in May, conditional on his passing a food handling exam.

“If it wasn’t for Osborne, I don’t know what I would have done,” said Torian, noting that Osborne Association staff helped him create a resume, assigned him a career counselor and mentor, taught him how to finesse job interviews and “hooked me up with a suit,” to favorably impress interviewers.

“He’s doing absolutely exceptional,” and has “hit the ground running,” said David Thorpe, program manager for Osborne’s Training to Work program, which helps ex-offenders forge fresh careers they can develop over a lifetime.

The Obama commutations and pardons are an important vote of confidence for the fortunate few who received them, Thorpe said, noting that “with a little bit of help, people can succeed.”

Receiving a miraculous “get out of jail” pass, courtesy of the president, “is really a blessing. It’s like being given a second chance. I’m very grateful. I thank Obama from the bottom of my heart,” Torian said.