By JERRY TALLMER

Denis O’Hare inhabits Chekov’s ‘Uncle Vanya’

MARIA VASILYEVNA VOINITSKAYA: Forgive me … but you have changed so in the last year that I absolutely do not recognize you. You used to be a man of definite convictions, an enlightened personality …

IVAN (“VANYA”) PETROVICH VOINITSKY, her son: Oh, yes! An enlightened personality who never enlightened anybody … You couldn’t have made a more venomous joke. I am now forty-seven years old. Up to a year ago I deliberately tried, just as you do, to cloud my vision with all this scholasticism of yours, and not see real life – and I thought I was doing very well. But now, if you only knew! I lie awake nights in rage and resentment that I so stupidly missed the time when I could have had everything that my old age now denies me!

—Act I, “Uncle Vanya” (Ann Dunnigan translation)

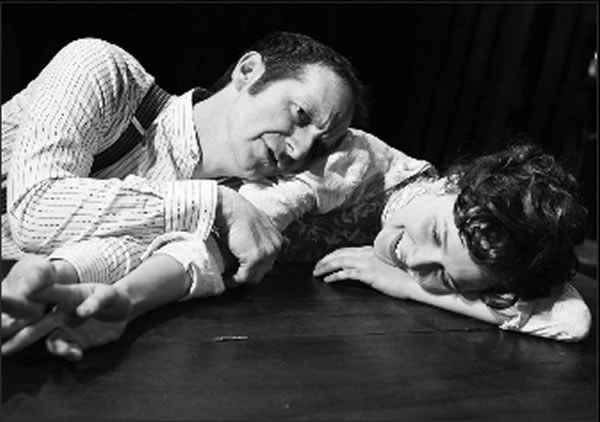

Irony is a big part of Denis O’Hare’s life and work, and the current kicker is that he has never played any Chekhov before, anywhere, much less the exquisitely complex, troubled, sensitive role of Uncle Vanya that he now fulfills with the Classic Stage Company on East 13th Street.

“This is my first,” said O’Hare a couple of hours before show time the other night. “And the irony is that I was trained to do Chekhov and have wanted to do Chekhov my entire life. So now, 25 years later … ”

The training was at Northwestern, where his teacher was David Downs, a disciple of the Alvina Krause, who was herself a disciple of Stanislavsky.

“To me,” O’Hare said, lightly but seriously as he chomped on an apple, “the important thing about Stanislavsky is: Where did you come from just this morning? What did you eat? What happened an hour before?”

This high-powered production costars George Morfogen as Serebryakov, the cranky old phony professor whom Vanya once worshipped but now despises; Maggie Gyllenhaal as Yelena Andreevna, the old professor’s gorgeous, langorous young wife; Peter Sarsgaard as Astrov, the self-contained doctor who finds himself, like Vanya, falling in lust, shall we say, for Yelena; Mamie Gummer as Sonya, the professor’s self-sacrificing daughter who – tragically “not beautiful” – is hopelessly in love with Astrov; Delphi Harrington as Maria Vasilyevna, Vanya’s fussbudget pseudo-scholarly mother; and Louis Zorich as Telegin, an impoverished neighbor, called “Waffles” because of his mottled complexion.

The production also reunites O’Hare and multi-talented Austin Pendleton, who more than once has himself played Vanya but is here the show’s director.

Indeed, one of the only two “Uncle Vanya”s that O’Hare has ever seen was at Williamstown, Massachusetts, in 1984, with Pendleton in the title role. The two men have worked together as performers in an out-of-town “Finian’s Rainbow” in 1999 – “Austin as the racist senator. I as a leprechaun.”

To O’Hare, “Austin is a great teacher, and he teaches while he directs. This production is a little unorthodox. We’re very free; we don’t have to stick to the blocking.” He notes that the text from which they work is “a translation, not an adaptation – no spin – by Russian scholar Carol Rocamora.”

If Pendleton can play a bad guy, so can O’Hare. The actor who so deservedly won a Tony, an Obie, and a Lortel Award for his hilarious/somber performance as Mason Marzac, the accountant in love with his gay baseball-great client in Richard Greenberg’s “Take Me Out,” can be seen at this moment in the superb movie “Milk” as John Briggs, the California state senator who (in the 1970s) joins Anita Bryant in wanting to kick all the gay teachers out of the schools.

That, given O’Hare’s own sexual orientation – he lives in Brooklyn with interior designer Hugo Redmond – is irony No. 1, compounded by the fact that in the film we see Briggs losing debate after debate to witty Harvey Milk.

Which leads to a yet further irony. In O’Hare’s words: “The director, the producer, and the writer of the film are all gay, so they felt pretty confident in hiring a straight actor” – brilliant Sean Penn – “to play Harvey Milk.”

And here are a few more ironies, closer to home:

“I was born January 17, 1962 – Chekhov’s birthday,” said O’Hare, though some Internet sources put that date as January 29 [1860]. “They’re wrong. It’s January 17. And our first performance here was January 17.”

Then there’s this: “Uncle Vanya was 47 years old. I turned 47 the day of our first performance.”

And Vanya felt his life was over, interjected this journalist.

“Yes,” said Denis O’Hare, “and mine is just beginning.”

Why do you think Chekhov speaks so directly to us, said the journalist, pushing his luck while thinking back to the stunning off-off-Broadway “Uncle Vanya” starring George Voscovec, Franchot Tone, Peggy McKay, and Gerald Hiken, produced and directed in a basement on East 4th Street by the late David Ross, 53 or 54 years ago. (It flung open the doors for me, is all I can tell you.)

“There are two spheres into which Chekhov falls,” said O’Hare. “The actor’s experience and the audience’s experience. Actors love Chekhov. It’s the best stuff to act. Audiences don’t always love Chekhov, don’t always get the same experience actors do.

“I mean,” said O’Hare, “Chekhov is ultimately about behavior and human nature, and not so much about plot. It’s multi-level, multi-layered. There’s no one answer” – Vanya shoots twice at hateful old Professor Serebryakov, misses both times, absurdly, and that’s only Act III – “and it demands that you be truthful.”

Stray thought: If only Dan White (actor Josh Brolin) had missed Harvey Milk, instead of killing him …

Denis O’Hare, born in Kansas City, raised in Detroit, has a brother and three sisters …

Chekhov again …

“Yes!”

John O’Hare, father of the above brood, worked in labor relations for Bendix. Denis’s mother, Karene O’Hara, died this past October. In the program biographies he dedicates this performance to her.

Last question: Has Denis O’Hare known any real-life Uncle Vanyas?

He mulls it over before answering: “I think most of us have had a Vanya moment in our lives.” A last chomp of apple, and that’s it.