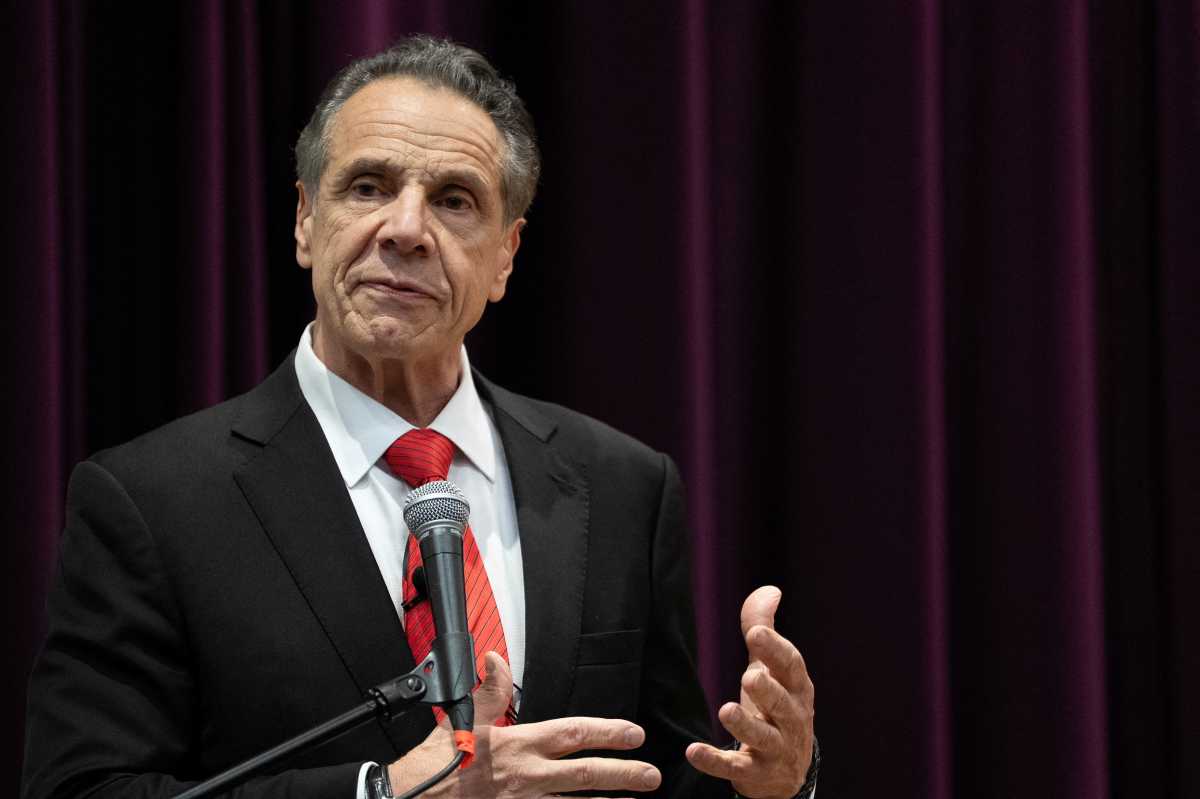

Former Gov. Andrew Cuomo said Sunday that, if elected New York City mayor, he would begin relocating people with serious mental illness from Rikers Island to supportive housing within the first 30 days of his administration.

Speaking at a Metro IAF gathering in Brooklyn, Cuomo also pledged to reinstate a pandemic-era policy of nightly removals of unhoused individuals from subway trains and stations, saying it would help assess needs and connect people with services.

Cuomo, the current polling frontrunner in the Democratic primary, called the troubled jail complex “an absurd disgrace and abuse of taxpayers” and vowed to move non-violent detainees with significant mental health needs into community-based group homes and treatment facilities. He did not specify how many people would qualify or outline logistics beyond the 30-day timeframe.

Under his proposal, only individuals who are not charged with violent crimes and are not considered a danger to others would be eligible for transfer.

Rikers Island has faced mounting criticism and federal oversight due to persistent violence and unsafe conditions. In March, a report by the Independent Rikers Commission found that of the 6,800 inmates, 57% of the jail population has a mental illness, including 83% of women. Around 1,400 detainees, or 21%, are classified as having a serious mental illness.

“As Mayor, I will begin having the significantly mentally ill removed from Rikers within 30 days and placed in community group homes and supportive housing with appropriate mental health facilities, provided that they are not a danger to others or have not been accused of a violent offense,” Cuomo said. “This will generate tremendous savings, as supportive housing beds, on average, cost approximately $24,000 per year.”

By contrast, the Commission reported the annual cost of incarcerating someone at Rikers is roughly $400,000.

Cuomo’s remarks come as Rikers awaits the appointment of a federally mandated remediation manager, following a court order placing the facility under receivership last month. The manager will be responsible for addressing constitutional violations, especially related to safety, leaving the fate of the planned 2027 closure of the complex uncertain.

Cuomo’s subway homelessness plan echoes COVID-era practices, which he argued were effective in stabilizing transit safety and connecting people with care. “The New York City subway system is not a sustainable living arrangement,” he said. “We know what works because we have successfully done it before. We will do it again.”

The homelessness and mental health proposals are part of a broader public safety platform at the heart of Cuomo’s campaign. His marquee proposal is to expand the NYPD by 5,000 officers — a 15% increase — bringing the total force to nearly 39,000. His campaign argues the cost would be offset by reducing overtime spending.

Cuomo has also called for doubling the number of officers in the subway system to 4,000, installing faster, high-barrier turnstiles, creating an MTA fare-evasion enforcement unit, and appointing a subway safety director within City Hall.

Under his mental health plan, focused on prevention and crisis intervention, Cuomo proposes a centralized outreach unit, more low-barrier housing, expanded mobile crisis teams, and increased psychiatric bed capacity, including forensic beds. However, critics of Cuomo have been quick to point out his record on mental health services during his governorship, when his administration took hundreds of beds out of the state psychiatric hospital system.

When Cuomo published the plan on May 6, fellow mayoral candidate Brad Lander his plan to fix mental health crisis “is like an arsonist saying he’ll put out a fire.”

“Everyone knows that when Andrew Cuomo was governor, he deliberately gutted our mental health services, slashing thousands of beds, which helped cause the dire situation on our streets and subways that afflicts New York to this day,” Lander said.