Several former employees of Housing Works claim that the Downtown Brooklyn nonprofit fired them during the COVID-19 pandemic as retribution for their involvement in an ongoing unionization effort.

The Housing Works organizing group, represented by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, plans to file Unfair Labor Practice complaints with the federal National Labor Relations Board on Friday, alleging company leadership tried to rid four of their rank-and-file for being outspoken unionizers.

“I feel that I was targeted in a lot of ways because after we did go public [with our union drive], I was not reserved and quiet about my involvement,” said Rebecca Mitnik, a former Housing Works case worker and one of four workers in the ULP complaints.

Mitnik — who worked to connect clients who have HIV/ AIDS and are experiencing homelessness to various government support services — was among the early organizers of the push to unionize, talking to her co-workers in small sessions about working conditions.

The labor organizers eventually contacted RWDSU and launched their public campaign with a walkout from their Willoughby Street headquarters and a rally at Borough Hall in October.

As the pandemic hit the city in March, Housing Works laid off Mitnik after the company offices and stores closed their doors due to the viral outbreak, allegedly saying her position no longer existed — a claim she quickly cast doubt on.

“My position could not have been made redundant because they always need case managers, we have such high caseloads,” Mitnik said.

Within days she saw a posting for a new case manager role at Housing Works pop up on LinkedIn — furthering her suspicion that she was unwelcome at the company because of her collective bargaining push.

“It’s very clear to me, ‘We do not want you specifically,’” the Coney Islander said.

The sudden move left Mitnik stranded in the middle of a global health crisis, with her company health insurance expiring a day after she was laid off. She also couldn’t contact her clients because she was locked out of her company email account.

“I couldn’t terminate relationships with my clients, I couldn’t tell them I wasn’t abandoning them,” she said.

Another former employee, who was also a prominent figure in the union drive, was furloughed around the same time as Mitnik, before the company let him go entirely soon afterward without offering him a new position, he claims.

“I applied for four positions at the bookstore [in Manhattan] — never heard back,” said Eric Fretz, who worked part-time at the Housing Works Park Slope thrift store on Fifth Avenue.

Housing Works chief executive officer Charles King told Gay City News in August that “every single person who Housing Works laid off” was offered “alternative positions,” but both Fretz and Mitnik say that wasn’t the case for them.

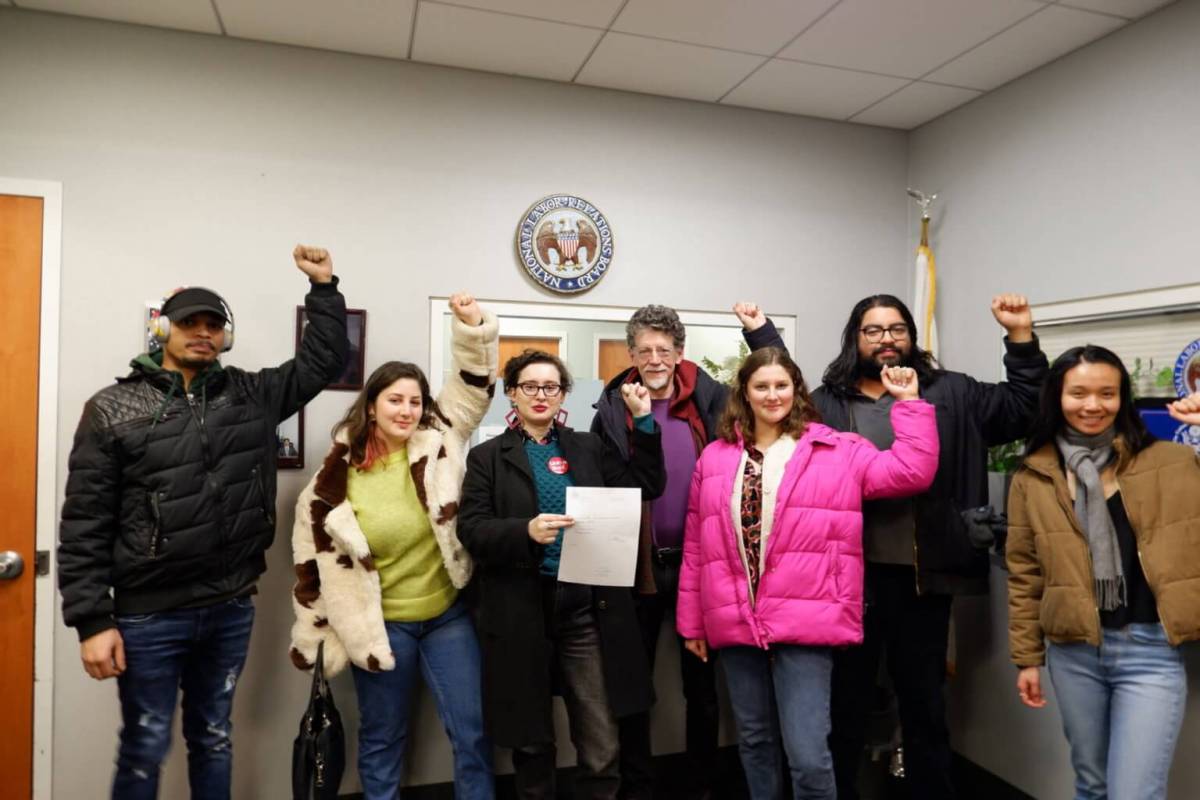

Fretz had gone door-to-door to other Housing Work outposts to sign people up for the union drive, and — along with Mitnik — was among a handful of workers to drop off the more than 400 signed union authorization cards out of some 600 employees at the district office of the National Labor Relations Board in Downtown Brooklyn in February.

“My face was known by all these different [store] managers as the person going around doing this,” Fretz said.

Their complaints come after workers and union officials blasted King for trying to draw out a vote on union certification, which was supposed to take place on March 20, before the NLRB halted it due to the pandemic.

The NLRB rescheduled for mail-in ballots to go out by July 31, but Housing Works appealed to the Board’s Donald Trump-appointed Washington, DC, office on July 23 which paused the proceeding until further notice while they considered whether to review Housing Works’s opposition.

The nonprofit wants the Board to throw out the petition, arguing that Housing Works’s business model has shifted significantly since it started operating two COVID-19 “isolation shelters” in hotels, employing some 80 people.

If the DC Board decides to review Housing Work’s complaints, that could delay a vote for another six months to a year, feared one union organizer, who said this was just another tactic by the company and their attorneys at Seyfarth Shaw LLP to run out the clock on the almost one-year-old union drive.

“What they tried to do is what we call ‘flood the unit’ with people that are not that trained and don’t know about the union and are easily swayed,” said RWDSU organizer Adam Obernauer. “The pandemic opened the door for them to union bust and they took that opportunity and ran with it.”

The president of Housing Works, Matthew Bernardo, denied that any of the company’s 196 total furloughs and layoffs since March were a result of union activity, noting that they still employ union campaigners and that they were simply trying to have all employees have a say in the union vote.

“Housing Works has been neutral throughout this union organizing process, and we did not and would never target an individual employee for layoff or furlough based on union activity. In fact, we still have staff who were involved in the union campaign, and we’re happy to have them,” Bernardo said in an emailed statement.

His continued by saying that they offered “newly available opportunities” at the company to all employees who were laid off permanently, but declined to comment on individual cases.

“Every time an employee was permanently laid off, we shared with them a list of newly available opportunities at Housing Works and invited them to apply,” he said. “It was up to the employees whether they wanted to apply for a position or not.”

This story first appeared on our sister publication brooklynpaper.com.