More than 50 percent of working families in New York City can’t afford their basic needs, according to a study released last month that amNewYork Metro reported on.

The report, titled The True Cost of Living in New York City, was released on April 25 by two nonprofits, The Fund for the City of New York and United Way of New York City. The report looked at what it takes to make ends meet in New York City and considered factors including race, gender, household size, and location.

To follow up on these findings, amNewYork Metro spoke to several Bronx nonprofits that offer career and workforce development, along with other social services, for mostly Black and brown New Yorkers in the central and South Bronx areas — communities and regions that the report showed had the highest income poverty in New York City.

Nonprofit leaders shared their thoughts about the report’s findings and offered solutions towards advancing economic prosperity for New York City’s most economically disadvantaged.

Gregory Morris, CEO of the New York City Employment and Training Coalition

“The coalition has been around for 25 years and has been focused on policy and advocacy for workforce development providers in the city. There are 220 organizations under the New York City Employment and Training Coalition umbrella serving 200,000-plus New Yorkers every year. We’re the ones who are helping folks find access to job opportunities, especially for New Yorkers who have vulnerabilities or challenges — whether you’re looking for a first job, career change, or “up-skilling” or “re-skilling.”

We were called to table from the very beginning as the data was being captured and the (True Cost of Living in NYC) report was being formulated, to think about what the best policy recommendations would be for this report. If we’re going to think about quality jobs, we’re going to have to think about wages and we’re gonna have to think about what financial security looks like. We have to really try to understand these numbers in a city that is increasingly unaffordable to a lot of folks.

Oftentimes, employers that I meet with say to me things like, “We have jobs we can’t fill,” because we don’t know where the job seekers are, which says something to me about how they think about what New York talent looks like, or what New York talent is. If you add layers of people with vulnerabilities, whether it’s folks who have history of being justice involved, a history of housing issues, or mental health needs or disabilities, they will tell you across the board: Entry-level jobs that lead from internships to employment placements are limited.

We’re at a moment in time where our public school system or higher education model, CUNY in particular, both need to evolve to prepare students for the workforce and to be able to create strong entry points. The starting point is saying, “Let’s talk about what your soft skills are. Let’s talk about your career interests. Let’s talk about how it is that you’re capable of presenting yourself to an employer successfully.” We call it job readiness. At the same time as I’m doing that, providers need to make sure that all of the supports are in place for potential barriers, whether it be related to mental health needs or housing stability needs. We call that bridge programming, supportive services, or wrap-around support.

That entry point only matters if the wage floor is high enough. We all need to be clear from the starting point: that inequity is historic, systemic, related to racial bias and systemic racism. Let’s start from the wage gaps that exist.

It tends to be the jobs that women and people of color have taken — specific sectors, occupations, and jobs that are essential to our welfare as a city — but they start at a low wage. We need to make special investments in the disproportion that exists — whether it’s the higher unemployment rates for Black and brown New Yorkers as opposed to white New Yorkers or whether it’s the wage gap that exists between women.

To raise the wage floor, we need to put a specific focus into the occupations and the individuals that are disproportionately behind to get them ahead to where they are competitive, successful, and secure in the city. If you look back — my career in New York City started 30 years ago — almost the same neighborhoods that were struggling 30 years ago are the same neighborhoods that are struggling today in poverty and unemployment.

Employers have to be intersected with workforce development providers. There are industries that are growing in the city right now that we are not ready for because of so many disconnections and fragmentation in our economic development and workforce development systems.”

Christina Hanson, executive director of Part of the Solution (POTS)

“The POTS organization provides comprehensive and personalized services, including food security program, wellness program, case management and legal services — serving around 37,000 people mostly in the central Bronx. 75% of our clientele is Hispanic and the rest are Black. 40% to 50% are English-language learners.

One of the things that you can see from the (True Cost of Living in NYC) report is just the number of New Yorkers that are currently struggling to meet basic needs — specifically, in the central Bronx. This is something POTS sees on a daily basis. It’s because their income is insufficient to meet needs they have in their lives. It’s not just about whether or not you’re working. It’s that many jobs in New York City aren’t paying enough and they’re not consistent enough to help people live sustainably.

There’s an absence of childcare with a low-wage job. Accessing work without childcare is extremely difficult. There are some subsidies out there to help people try and access them. But the bureaucracy around accessing some of those childcare subsidies is really just incredible. It’s constantly getting rejected for benefits for all sorts of silly reasons. One example is a woman who wanted to have childcare to be near where she worked instead of near where she lived. It was easier for the pickup and the drop off. And (the childcare) was just too far from where she worked.

If people are Hispanic and they don’t speak English fluently, that already limits the job options you have available to you. Depending on your immigration status, that also limits the political will too. So in general, you’re going to find that navigating the system is much harder. Even if you can access some benefits if you can find them, getting a job that can cover the costs of both you and your family is challenging. It’s just one of these things where a number of barriers come up throughout the process. It’s just so hard to figure out what the right tradeoff is.”

Daniel Diaz, executive director of East Side House Settlement

“East Side House Settlement is an education and workforce development settlement house located in the Mott Haven section of the South Bronx that serves around 14,000 families a year. We have 29 locations. Many of them are in schools and community centers. Some are at after-school programs and a lot of them have full-time staff working at those schools to provide the social-emotional learning and the career development.

A majority of our programming leads to some type of employment work. About 250 young people we’ve placed into jobs per year — that could be doubled, tripled, quadrupled. We have about 2,000 11th and 12th grade kids that we work with every day. I have CNA (Certified Nursing Assistant) classes and OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) classes for kids. We’re about to put in some of the training for EKG (Electrocardiograph).

We have nine community centers, three of which are older adult centers. We have at-risk youth workforce programming at our community centers. Our youngest participant is 18 months and our oldest is about 98.

My first reactions to the (True Cost of Living in NYC) report was not being very surprised. I can tell you working in the streets and working where we work, there’s a lot of people unemployed and underemployed.

I think most of the workforce development practitioners would feel the same way. There are a couple of things that I would like to highlight in terms of what we’re seeing on the ground: Childcare from the ages of zero to three seems to be a very big hold up for families that are looking to get back into work — whether it’s working full time or part time. Trying to make sure that children are cared for would be something that would be beneficial to this population in general.

Most of the population we’re serving here in the Mott Haven area are Latinos. This is an ever-changing situation, but yet everything’s staying the same. Before it was Puerto Rican and Dominican families we were working with. Now, it’s more Central American and Mexican families we are working with. Some of these individuals are not speaking Spanish; they’re speaking indigenous languages.

The second response off the hip is we need to really rethink what our K-12 education looks like. I feel like we do a disservice when we’re only training to get to the English-language learner exam or the math exam. Language acquisition is is a problem for many individuals. The people that we are serving currently at Eastside, a lot of those language issues we encounter are more in the early grades. By the time they’re getting into their their high school years, maybe 20% to 25% are English-language learners. They learn just enough to pass their language proficiency test. And then all of a sudden, we’re expecting them to be proficient and then wondering why they’re failing in school.

We’ll have maybe four or five new migrant families now, but about 20 new migrant families per week were coming in during the height. In total, we helped with 200 families. A lot of them are in The Bronx.

From third (grade) all the way up until they hit high school, then we’re getting them ready for the Regents’ exams. After that, we leave it up to the colleges and young people to figure out what what they want to do, but a lot of people don’t make it to that phase of college. There’s a work exploration part that is missing for this population.

You have all these green jobs that people are talking about, but none of those training programs exist until you get out of high school.

I’ve spoken to CUNY before about embedding their continuing education programs and getting kids graduated with a high school diploma and certification. It kind of fell on deaf ears. Instead of the College Now program, I would want them to come up with continuing education programs and work with young people as to what they’re interested in, and then change with the times.

Healthcare, green jobs, and construction seems to be some of the biggest desired jobs. The last one is a very low-paying situation: the food industry. If we can figure out the wage scales on some of those, that would help, because if anybody’s ever gone to restaurants, there’s a lot of Latin folks working in the restaurant business. They’re working, but they’re not able to make ends meet. The wages for kitchen work is just so poor — it’s terrible.

It’s been extremely difficult to get (undocumented people) into construction. It’s almost like a “hush hush,” because the unions will get upset if somebody finds out you have a day laborer that’s non-unionized working on a construction site. The food service industry was very helpful with things like that.

If the city would like to help, we can start really talking about what a pay equity looks like, and looking at skills and degrees instead of just degrees in order to get people certain jobs. Thinking about what the Earned Income Disallowance looks like on the NYCHA front, where if you make a certain amount of money, your rent will go up. If the disallowance could be extended a bit further, it might help families.

Let’s wipe the political thing out for a second. Let’s figure out a path to documentation and figure out a path to them working. I don’t want to oversimplify it. But if they were to get their documentation, these families will work their tails off. They’re working their tails off anyway. I am pretty sure some of them have some schooling that took place in Mexico. Let’s get some reciprocity on what that schooling looks like and get them to where they need to be in terms of training, and put them in jobs that they can be successful. I see them hustling just as much as everybody else.”

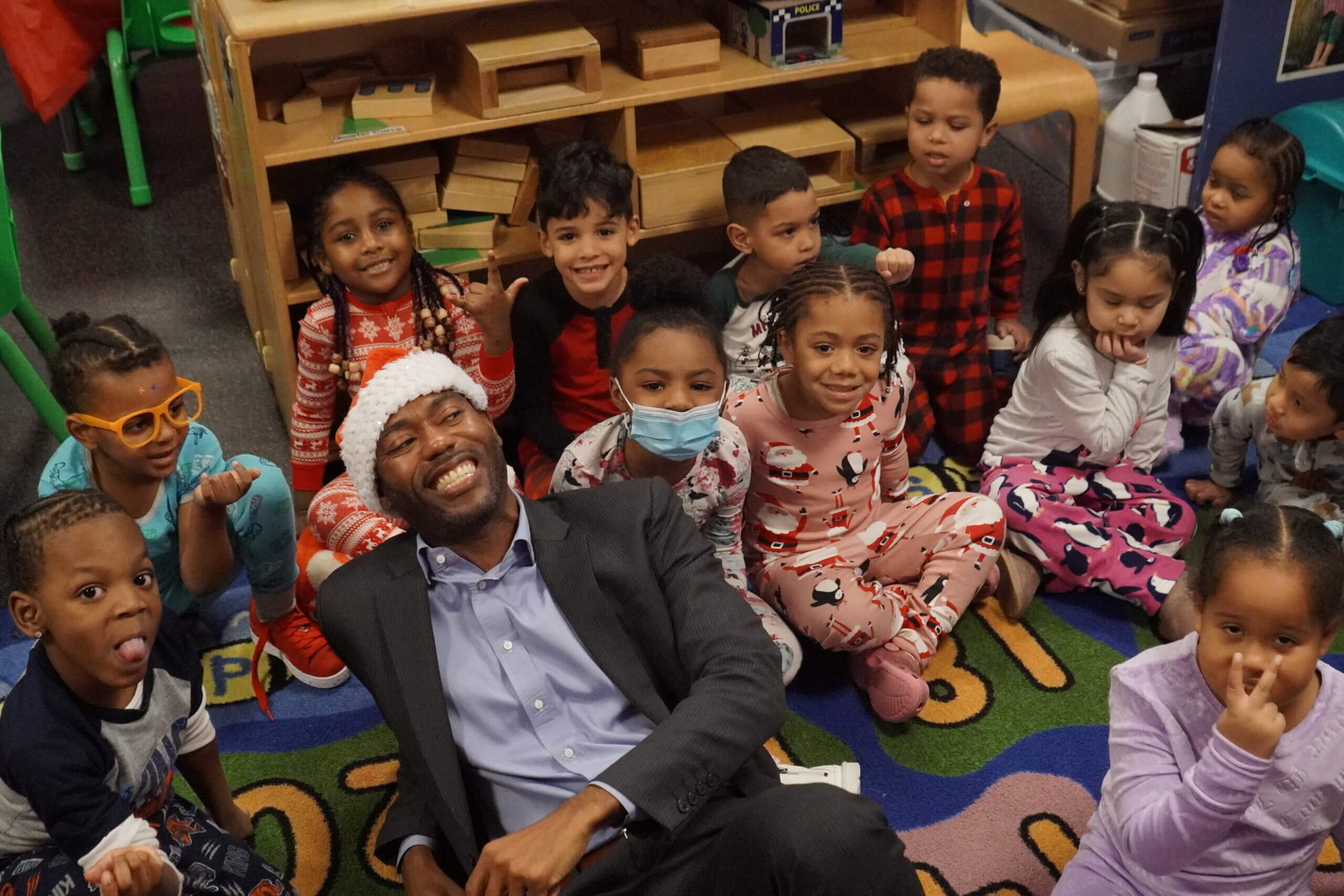

Andre White, executive director and CEO at Phipps Neighborhoods

“We’re a social service organization that was founded in 1972, so we turned 50 years old last year. We were created as a means to provide support to our sister organization, Phipps Houses, the largest affordable housing developer, owner, and property manager in New York City. Phipps Houses serves 21,000 residents across all boroughs, except Staten Island. We currently serve 14,000 residents in West Farms, Melrose, and Soundview.

We have after-school programs where we provide good engagement for young people in high school and elementary schools. It’s really anchored in workforce development. We provide jobs not only to young people, but also to adults. There’s two approaches to the way we think about workforce development. We provide training opportunities where we are actually providing industry recognized credentials. We’re able to provide an opportunity to interview with a job that pays a living wage that comes with benefits and insurance.

If you have some sort of family emergency that could take you away from work, we provide what’s called follow-up services. That’s us calling our folks if they reach out to us if they need MetroCards, food, support — my staff is there to make sure that they feel supported.

We have a team within our workforce development and education department. They’re tasked with being boots on the ground every day. They’re in communities knocking on doors, talking to folks. We launched a brand new workforce development program last October around the building services sector. A friend of a friend got one of the flyers and he went through the training program, came to us and got a job at Phipps Houses — full time with benefits.

We have our career Health Care Network training program in partnership with Montefiore that we run for young people ages 16 to 30 years old. They go through 10 to 12 weeks of classroom learning. We have young people who have gone on to make $50,000 to $60,000. They’re all working at Montefiore or NewYork-Presbytarian or other companies in the healthcare sector. It’s been quite successful.

These (True Cost of Living in NYC) findings are disappointing. But I think it’s a good baseline to actually see that data to give a true sense of what needs to be done collectively. Our goal is to expand our two training workforce development programs to another three or four over the next couple of years.”

John Weed, assistant executive director at BronxWorks

“BronxWorks is based in the South Bronx with over 50 locations throughout The Bronx and serves roughly 65,000 individuals and families per year. We’re a settlement house and we have everything from childcare, family programs, case management, and senior services. We’ve recently taken on a migrant shelter for people being bussed in. BronxWorks started as an information referral and benefit assistance where we see people who are in need of basic services. We’re actually in now Soundview and in the north Bronx.

I know The Bronx pretty well and the people that are living here. The demographics have definitely changed over the last 30 years, but the poverty seems to stay the same. Now there’s a lot of Central American and Mexican immigrants. We also have Bengali group that has moved into The Bronx, and a lot of West Africans.

We work with a lot of immigrants. English is key to getting better employment, plus we have basic education classes, which include GED prep. We do a lot of recertifications for people who already have subsidies and we work with people to find better housing with what subsidy they have. But we’re a long way away from fixing everything.

There was a higher level of poverty among Latinos and even Black families. I expected maybe the reverse. We saw in the pandemic — a 25% unemployment rate hit The Bronx — those that were working were mainly working low wage service jobs. We’ve gotten into some other sectors that can provide some better pay. For example, there’s a lot of housing developments now in The Bronx. You see a lot of buildings going up. They’re all mostly low-income housing projects, but with those projects, they need a labor force. We’ve been working to train people in OSHA, scaffolder, hazmat — different credentials that people can use to go on these job sites. Those generally pay a better wage, although they’re not unionized, so they’re not secure jobs.

It’s a tough thing here with a lot of entry-level workers. We have a grant through the Robin Hood Foundation where we do GED prep, and then we put people on a track for either college or work and the foundation is pushing us to really find jobs that exceed minimum pay.

We’ve hired a lot of entry-level workers to work in our after-school program, summer camps, and back office, so that’s a way for people to get started. We have a workforce of 1m000 people and there’s always opportunity for advancement.

New York City has a wealth of social service nonprofit agencies. I think we’re really lucky to have that. But what we don’t have help with is mental health. Mental health has come to the forefront with us, in our youth population, certainly, since the pandemic. We’ve had meltdowns and we had a recent incident where if we had mental health clinicians on site at night, that might have been a different situation. There’s a lack of mental health facilities, a lack of professionals, and a lack of ability to link up with services.

We’ve now entered into certain programs at the George Washington University. They have a pilot project where they’re training some of our line staff to do some mental health treatment. We’re getting trained in meaningful listening and feedback and how to how to approach clients who exhibit mental health challenges. Those are minor advances, but real clinical interventions and commitments with health facilities would be much better if we could connect and get those kinds of collaborations.”