BY EILEEN STUKANE | At the moment there may be détente between the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PA), elected officials, and community leaders, over the PA’s plans to reinvent its time-worn bus terminal — but it is yet to be determined just how far the PA’s commitment to heeding the community will go. There is a promise to hold future public meetings, and there will be plenty to discuss about five new plans unveiled by the PA last week.

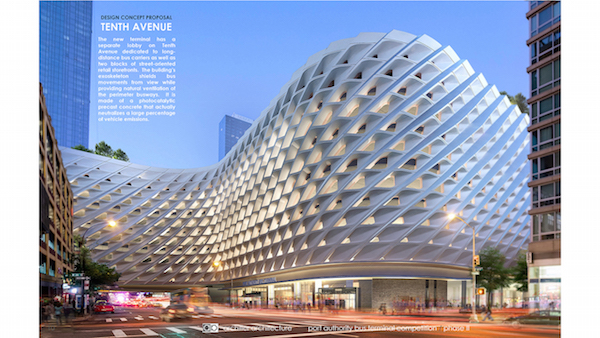

The five designs, each from a different architectural firm, range between $3.7 billion and $15.3 billion, with one scenario including underground passageways and tunnels, one utilizing the Javits Center, another connecting to Times Square, and another with a rooftop park which requires demolishing neighborhood buildings by invoking eminent domain (the right of a government or government agency to take possession of private property for public use).

The PA’s initial 2015 concepts for creating a new bus terminal strongly relied on eminent domain, which “would tear out the heart of the Hell’s Kitchen [HK] area directly across the street,” said Community Board 4 (CB4) member Betty Mackintosh at a recent CB4 Clinton/HK Land Use Committee meeting. Those plans, which she cited as “flawed and secretive,” would have obliterated homes, local small businesses, and community institutions. Mackintosh now heads CB4’s HK Working Group, which has been collecting a broad range of information about the Hell’s Kitchen South area (i.e. air quality, number of residences) in order to “battle with the Port Authority,” as Mackintosh said at the meeting.

Another weapon in CB4’s fight for the community is the possible creation of a Hell’s Kitchen South Historic District, proposed to be an area from Eighth Ave. to just west of Ninth Ave., between W. 40th and W. 41st Sts. to W. 34th St. A landmarked section of the city cannot be easily altered, and the use of eminent domain cannot be employed. The idea for the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) to designate this section of Hell’s Kitchen as a historic district actually first surfaced within CB4 during 2010.

“A body of research was done in 2010, but the work was tabled [by CB4] in deference to other more urgent matters at the time,” explained Dale Corvino, a CB4 member who, along with CB4 public member Brian Weber, is spearheading the CB4’s Landmark District Working Group. “The work was reactivated when we saw the continued loss of significant buildings and the plans of Port Authority,” he said.

“The historic district has been in the minds of some neighborhood people for some time,” said Rev. Scott Stearman, pastor at Metro Baptist Church (which, at 410 W. 40th St., would be within the proposed historic district). “I think this [the PA’s plan] has added a bit of energy to the fire,” he added. “I do see it as a tool in the toolkit. I’ve been appreciative of all the elected officials. If they [PA officers] are going to make this kind of transformative change, then it really needs to be thoroughly vetted, and all stakeholders engaged.”

Corvino explains that what’s gained by a historic district designation is that “the buildings that are within a historic district, and of historic significance, can’t be demolished. Being within a historic district saves them, and that’s the goal, to prevent further demolition.” He notes that the PA’s outlines of its building plans included Hell’s Kitchen South areas where streets are lined with early 20th century industrial buildings of 10 to 20 stories, with setbacks that bring light and air into the streets. “Some of the buildings are more significant than others,” says Corvino, “but it’s not so much about an individual building that we want to save, it’s about an area of buildings of a certain character that we’d like to prevent from being lost forever.”

JD Noland, chair of CB4’s Clinton/HK Land Use Committee, however, noted that CB4 is only in the early stages of its drive to create a new historic district.

“The process has just started,” Noland said. “We’ll discuss it, get some ideas, fill out the LPC form. Once we do that, we’ll talk about it in committee, take it to the full board, [and] say, ‘Here are some of our ideas.’ It takes time to figure out.”

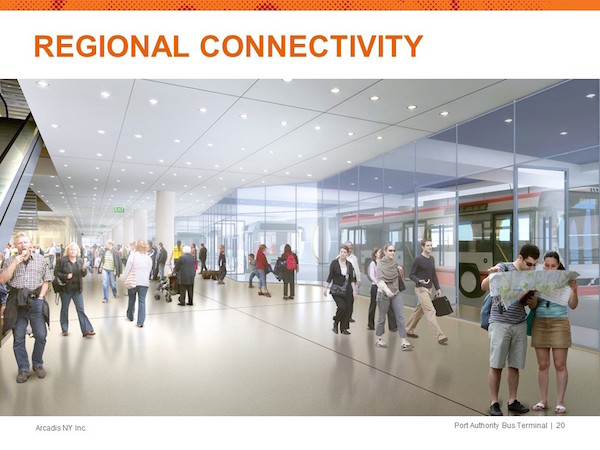

Meanwhile, the PA is moving along as New Yorkers wonder why a new bus terminal has to be established in an increasingly densely packed New York City. On its website, CB4 reports that on one weekday, the PA bus terminal accommodates approximately 220,000 passenger trips and more than 7,000 bus movements. Estimates are that by 2040, peak-hour passenger traffic will increase between 35 to 51%, and bus traffic will jump up 25 to 39%. Yet there is no hope of constructing a terminal in New Jersey; the PA is adamant about staying on Manhattan’s West Side.

“They want to take over Hell’s Kitchen and make it part of New Jersey,” says Noland. “The New York side is pushing back and saying, ‘Wait a minute, you should have something in New Jersey and not destroy the neighborhood here.’ ”

Rev. Stearman summed it up like this: “Clearly the New Jersey side does not want it over there. I think everybody in Manhattan has to think, ‘Why in the world do we want to bring all those buses in?’ With transportation technology today, there seem to be a thousand reasons to have it [the bus terminal] across the river.”