By Albert Amateau

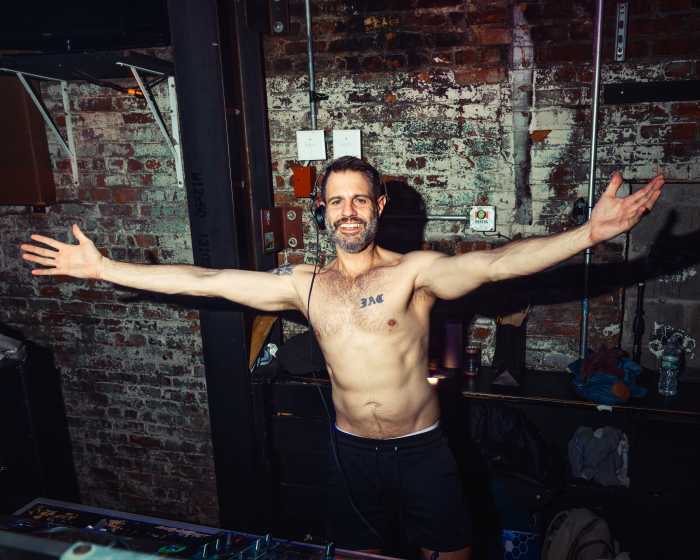

Edward Boks, executive director of Animal Care and Control of New York City in Lower Manhattan since January 2004, speaks with a preacher’s intensity when talking about the “no kill” goals of the city’s official animal control agency.

His persuasive fervor is partly explained by his background as a former minister of a small non-denominational church in the Phoenix, Ariz., area and the director of the church K-12 school.

Back in Mariposa County, Ariz., a part-time job that Boks had taken in the local animal control agency to supplement his earnings as the school director turned into passionate calling. The treatment of the animals appalled him and he became so involved in reforming the agency that he eventually became its executive director.

“It’s the largest animal control agency in the nation, New York City is second,” he said, explaining that Mariposa Co. is bigger than some states and includes fast-growing towns and suburbs of Phoenix.

Boks, who earned a national reputation in the field of animal care and control as a leading figure in “no kill” philosophy, came to New York City two years ago as a consultant to help restructure the city’s animal control agency. Animal Care and Control was organized in 1995 as a not-for-profit charity with a contract as the official animal welfare agency after 100 years of A.S.P.C.A. Boks’ national reputation recommended him to head the city agency.

“It was my first week on the job in 2003 and we took in a Bengal tiger from Harlem,” he recalled in an interview at his office. “I thought it was going to be a regular thing.”

For a while, he split his time between Phoenix and New York, but became full time director in January 2004. The New York agency deals with about 50,000 lost, strayed and rescued cats and dogs — the figure includes about 4,000 wild animals — but not many tigers. “We will get a run of alligators every once in a while,” Boks said.

For a man who grew up in Michigan and spent much of his life in Arizona, Boks, 53, has become an enthusiastic New Yorker, with a deep appreciation of the diversity — and good will of the people. Living in the Village near Washington Sq. is a big plus for Boks, who gave some thought to where he wanted to live in New York before he came here. “I’ve always admired writing and Greenwich Village is famous for writers,” he said.

Caring for and controlling the huge number of stray and lost dogs and cats in New York City with as little killing as possible is a huge job. In the year since Boks has been full-time director, 23,465 animals were destroyed, a 17 percent decline from the previous year and the lowest in city history. “We have records going back to 1874,” Boks said, “back in those days they killed 300,000 a year, drowning in the East River.”

Figures for the first three months of this year indicate that another 15 percent decline is a realistic goal for 2005. Adoptions have increased over the past year by 105 percent and New York has taken a lead in no kill animal control. Adoption programs, low-cost and free spay and neutering services are gaining popularity. Special initiatives to connect animals to people are among the key strategies of the agency.

“Our goal is to have no euthanasia after 10 years,” he said.

The agency has about 150 employees, three shelters — the one in Manhattan on E. 110th St. between First and Second Aves. has kennels for about 400 animals — and a main office at 11 Park Place just west of City Hall. The $7.2 million annual budget from the city covers the basic cost of the agency,

But volunteers form the core of many of the special programs. Money raised from private sources, currently about $200,000 a year, funds those programs. One is Safety Net, which helps pets and their families stay together through difficult financial times or dislocations. TLC (Teach Love and Compassion) provides training and possible employment in animal care to youth from inner-city neighborhoods. STAR (Special Treatment and Recovery), for animals with medical or behavior conditions that make then unlikely for adoptions, provides time and care in family settings until the animals are sound and socialized enough to be adopted.

Every so often, A.C. & C. agents get a call from the neighbors of people who have dozens — or even hundreds — of cats in an apartment only big enough for five, Boks said. “We’ve had situations where there were 300 cats in an apartment, he said. “One of the things we did in Mariposa County was fund a study of hoarding, animal hoarding. We’ve been able to get the Department of Health here to hire a counselor who can help treat people with that obsessive neurosis. If we just take the animals away, you can bet they’ll have another 100 cats in the apartment in a few months.”

Boks insists that bad treatment, not breeding, makes for vicious dogs. “Take it from me — no dog breed deserves a bad reputation. Dogs mostly will to anything to please, we have a saying, ‘It’s the deed, not the breed,’ that makes animals act badly,” he said.

Since moving to New York, Boks, has only been the foster caregiver of cats, getting them healthy and fit enough for adoption. “I’m partial to boxers. I think they’re a wonderful breed,” he said. “I have two in Arizona staying with my son. But by this time, I’m sure they’ve bonded with him and his family so I’ll have to give up the idea of ever getting them back,” he said. The name Boks is Dutch, and the word means boxer, he observed. “I didn’t know that until after I got my dogs,” he said.

Boks likes to quote Gandhi’s declaration that you can tell the moral state of a people by the way it treats its animals. “When you think of it, animals are totally dependent on us. The way we treat them is a nexus of compassion that cuts across all levels of society,” he said. “People think of animal welfare as a liberal issue, but it’s not always true. Conservatives are also drawn to it. — I have to admit that I tend to be conservative,” he said.

Boks likes to call himself an “aspiring” vegetarian because he does eat fish. “I wasn’t always a vegetarian, but when you spend your whole day trying to save animals and then go home and eat them — it gets to you,” he said.

WWW Downtown Express