BY JACKSON CHEN | The Doe Fund, known for its men in royal blue uniforms that keep streets clean, launched a fundraising campaign last week in hopes of restoring street sweeping service to the Upper East and Upper West Sides.

Doe Fund employees typically patrol a route where they sweep streets, pick up litter, and perform general upkeep. Many areas served by the non-profit organization’s employees — most of whom come from a background of homelessness, drug use, or former incarceration — are funded by partnerships with area elected officials and neighborhood organizations to offer the workers minimum wage.

Those who worked on the Upper East and Upper West Sides had their salaries covered by the Doe Fund directly. Due to rising costs and expected wage increases, however, the organization had to cut the street sweeping services offered in those areas.

There are still Doe Fund-labeled trash cans that are looked after, but the men in blue “pushing the buckets” are no longer present in the routes that fall roughly between West End Avenue and First Avenue from the 50s to the 90s. According to the Doe Fund’s chief of staff, Alexander Horwitz, the service cutbacks were phased in beginning this year. The roughly 70 full-time positions have been displaced to areas where local funding is available.

The Doe Fund is looking at a significant rise in expenses when the minimum wage, which rose to $11 as of the new year, increases again to $13 by the end of 2017 and to $15 by the end of 2018.

“Those costs for us are incredibly enormous, so what we’ve been forced to do is suspend our free services and focus on the paying work we get and placing trainees in those more funded routes,” Horwitz said. “That’s why we launched this fundraising campaign, so that we can restore service in these areas we’ve been in for 25 years.”

He explained there is no exact funding goal, as the group will continue to add back service one job at a time as donations come in. If the group is able to restore all 70 full-time positions staffed, any extra money would go toward hiring more employees. An organization or local elected official could step up to provide the funding, but Horwitz said, “We haven’t been able to identify a large-scale person to make this happen.”

Noting that East 86th Street was one of the Doe Fund’s first routes, Horwitz said, “For the guys who have been a part of this from almost the very beginning, going without services on the Upper East Side is pretty sad.”

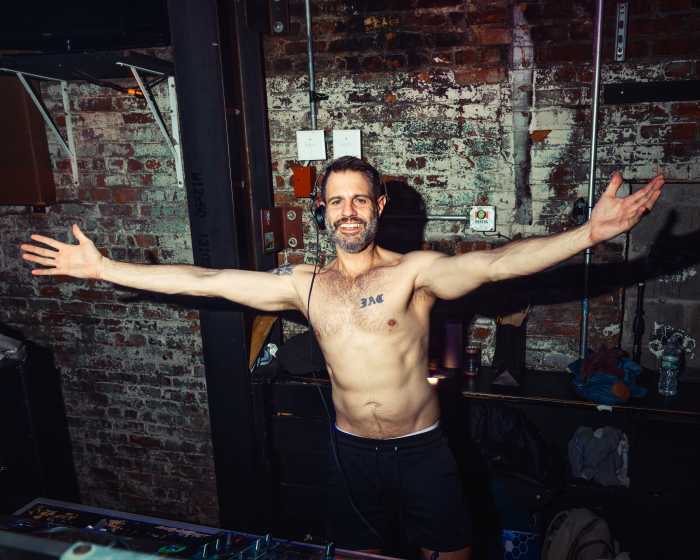

Craig Trotta, who’s been with the organization since November 1997, said the program was a win-win for the community and those looking for an opportunity to turn their lives around. Trotta, a Queens resident, began using drugs at 17, wandered in and out of jails, and landed as a homeless person in East New York. But a chance encounter with a former counselor at a support group made him aware of the Doe Fund’s work.

Trotta, like everyone else, started as a street sweeper for several months with an assigned route of Lexington Avenue between East 66th and 77th Streets.

“At first, I wasn’t too happy about it, but then I got used to it,” he recalled. “While pushing the bucket, it gave me some self-esteem back, letting somebody who never really worked before work. I was able to be responsible and it gave me back some peace of mind.”

He’s since moved on to become the Doe Fund’s senior director of community improvement projects, where he spends 12-hour days overseeing operations and serving as a role model for other trainees.

“November, I’ll be working here 20 years, and I didn’t forget where I came from, who I was, and where I could’ve been if the Doe Fund didn’t take me when they did,” Trotta said.

When asked about the impact of losing Doe Fund services in a broad swath of Manhattan, he said it would be two-fold: “It impacts helping a lot more men like myself to become productive members of society. And I think it hurts the residents and businesses in the neighborhood, not having the men in blue out there sweeping their streets and being ambassadors.”