BY JERRY TALLMER

Felled by cars & surfboards, artist is ‘more choreographer than dancer’

When I was a kid, I was taken more than once to see the glass flowers at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. They were beautiful and all that — indeed, quite miraculous. But to my memory they were not, piece by piece, very large, residing as they did (under glass!) in endless rows of display tables.

Dale Chihuly’s current exhibit at Marlborough Chelsea is nothing like that, except for the basic material of the whole shebang. Glass! Great, big, colorful roomfuls of glass interwoven with stainless steel and, on occasion, bits of denim.

The same is true for Chihuly exhibits anywhere and everywhere else in the world — and there’ve been a lot of them. But this is his first ever at Marlborough Chelsea.

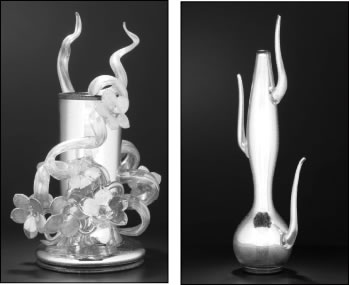

It’s a tripartite “site-specific” installation — a huge “Chelsea Persians” central free-form outburst with sidebars of “Silvered Venetian” and “Jerusalem Cylinder” variations.

Says the affable 70-year-old Chihuly over the blower (the phone, not the glasswork pipe) from his workshop in Seattle, Washington:

“For this first show in Chelsea, I wanted to create an environment, fill the space. ‘Chelsea Persians’ is all red and white glass attached to stainless steel armatures. It covers the walls, the ceiling, the columns. People can walk underneath and around it.”

Why Persians?

“Just a nice name.”

But a small, beautiful guidebook to Chihuly’s quarter century of evolving “Persians” stresses the impact of ancient Islamic art as perceived by the young American still in his 20s — who, in 1968 (as a Fulbright scholar), wandered the streets of Venice wondering what he wanted to do with the rest of his life.

In the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, he found himself facing a cycle of seven paintings by Vittore Carpaccio (c. 1460-1526) with backgrounds full of Islamic-influenced objects and implements. Nearly two decades later (1986), this revelation would flower into “Persians” — blown to life in a thousand forms by craftsman Martin Blank under Chihuly’s supervision.

For that matter, “Jerusalem Cylinders” is a back reference to the time an even younger Chihuly (whose roots were Czech, Hungarian, Norwegian, Swedish) spent working on a kibbutz in Israel. A half-century later, more than one million viewers would flock to “Chihuly in the Light of Jerusalem” in that city’s Tower of David Museum. Among the many other venues that have flourished one or more Chihulys are the Victoria & Albert Museum, London; the Salt Lake City 2002 Winter Olympics; and the New York Botanical Garden.

His wife is musician Leslie Jackson. Their son, Jackson Chihuly, is, says his father, “12 going on 20.” I forgot to ask if Jackson knows how to blow glass.

Artists have had workshops and assistants back, one imagines, to the unknown genius cave dwellers. Certainly Venice was once rich with such workshops.

Chihuly’s workshop (he calls it the HotShop) is in a former boathouse on Seattle’s Lake Union. There, by his count, some 85 assistants do everything that has to be done to turn out those gorgeous glass pieces, large and small. And pack them and load them onto trucks. And deliver them and unpack them and set them up.

He himself has long been knocked off the actual glassblowing by a head-on automobile collision in England (in 1976) in which he was thrown through the windshield — and a 1979 surfboarding accident that dislocated a shoulder.

His job, he has cheerfully stated, is “more choreographer than dancer, more supervisor than participant, more director than actor.”

There has to be something of a fatalist in him. His big brother George was killed in a training plane crash in 1957, when Chihuly was in his teens. Their father died of a heart attack a year later.

His mother saw to it that the boy got into the College of Puget Sound (now the University of Puget Sound) straight from high school in Tacoma. It was followed by time spent at the University of Washington, the University of Wisconsin, the Rhode Island School of Design and the Fulbright that took rolling stone Chihuly to Venice.

Some people want to be firemen. Some people want to be poets. And some people want to be sculptors in glass. It was Venice’s master glassblower Lino Tagliapietra who took the wanderer in hand and set him on his life’s course. A further boost was given when Chihuly, returning to the University of Washington (and now a better, more dedicated student), took courses in integrated glassblowing and weaving under Hope Foote and Doris Rockway.

All that is long ago and far away. Chihuly at Malborough Chelsea is now. You could lift a glass to it.