Mary Perillo, Kimberly Flynn, and Barbara Reich of 9/11 Environmental Action, working out of Perillo’s Cedar St. apartment, are continuing their efforts to enroll Downtowners who survived the 9/11 attacks in the healthcare and medical monitoring program recently given a new lease on life.

BY DUSICA SUE MALESEVIC |

The last-minute Zadroga Act reauthorization last month was cause for celebration Downtown — and especially for 9/11 Environmental Action, which has been on the frontlines of the fight for healthcare for survivors of the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

Congress first passed the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act in 2010. With only five years of funding for two programs — the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund, and the World Trade Center Health Program, which provides healthcare and monitoring for more than 70,000 Ground Zero responders and Downtown survivors. The reauthorization will provide funding many years into the future for the work of groups such as 9/11 Environmental Action, which does outreach to give survivors access to the programs.

“Now with the reauthorization of Zadroga, we have a lifetime of care,” said Kimberly Flynn, the group’s director and one of its co-founders. “We have 75 more years of the World Trade Center Health Program. This is unprecedented for communities.”

Flynn, who has been working for almost 14 years on issues around the environmental fallout of the World Trade Center attacks, emphasized the importance of 9/11 Environmental Action’s continued outreach, pointing out that there are many people who are still eligible for the programs but don’t know it.

Of the nearly 400,000 people Downtown who were exposed to contaminants after 9/11 attacks, only 82,000 — a little over 20 percent — have enrolled in the World Trade Center Health Program to receive healthcare and medical screening for the many aliments associated with the toxins that flooded the neighborhood, and which sometimes show up only years later, according to Flynn.

The renewed Zadroga funding will now provide an additional 25,000 treatment slots for survivors, according to Flynn, and 9/11 Environmental Action provides enrollment assistance to the health program and will walk people through the signup process, she said.

“It’s our job to make sure that people who need that treatment understand what this program [is], what it’s offering,” she said.

But Funding hasn’t been the only obstacle Flynn’s group have faced bringing Downtown neighbors into the program.

With the spotlight having justifiably focused on the first responders who rushed heroically to the scene, some local survivors who lived in the area may think that the program is not for them, Flynn said.

“There’s a lot of denial going on still,” said project manager Barbara Reich, who joined the group in 2009.

Communications Director Mary Perillo said she was surprised how many people in her neighborhood in the Financial District don’t know about the program.

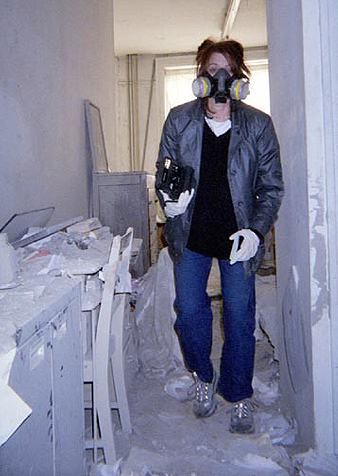

For 33 years Perillo has lived at 125 Cedar St., a residential building very close to the World Trade Center site. It took 18 months before she could go back home, which had been filled with inches of toxic dust, inside and out.

“We had to fight to come back in.,” Perillo said. “We had to fight to get clean. And 9/11 Environmental Action was instrumental.”

Formed in April 2002, 9/11 Environmental Action’s main struggle initially was to get the federal government to even acknowledge that there was an environmental safety problem at all.

“You cannot imagine how hard it was to push these issues,” said Flynn. “The federal government had absolutely no interest. Their position was ‘it’s safe, we reopened the area for business and we don’t know what you’re complaining about.’ On the federal level, there was a brick wall.”

Seven days after the attacks, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said the air was safe to breathe, said Flynn, and the city Health Dept. told residents to clean up indoor dust using a wet rag and a mop.

But Flynn said there was a lot of asbestos and glass in the smoke and dust, among other contaminants. As Downtowners tried to clean up, the dust caused eye injuries, rashes, and many nose and throat irritations, she said.

After successfully pushing the E.P.A. to finally do some cleanup, 9/11 Environmental Action also fought for a federal program that would address survivors’ healthcare. By 2006, first responders had the World Trade Center Worker and Volunteer Medical Monitoring and Treatment Program, Flynn said, and local residents had a pilot program that provided treatment for a small amount of people.

The group organized a town hall at St. Paul’s Chapel in 2006 calling for federal action to treat and monitor all those affected by the World Trade Center attacks.

“What we demand[ed] [was] a federally-funded program that has the capability of monitoring and treating the community of residents, the students and all of the office workers, all the area workers Downtown who’ve been affected by 9/11,” Flynn said.

It would take until January 2011 for the Zadroga Act to become law.

Now, with the reauthorization, Flynn said that their outreach and education mission is by no means done, and there are still survivors who don’t know they are eligible for the program.

“There are really likely tens of thousands of people who need the program now, or will need it,” she said.