On Jan. 21, 2020, New York City’s attention was on things that had nothing to do with their personal health.

In the news, movie mogul Harvey Weinstein was on trial for sexually abusing women. Yankee fans were celebrating Derek Jeter’s election to the Hall of Fame. The presidential race was hitting high gear, and President Trump was facing his first impeachment trial for abuse of power.

Offices from MetroTech to Midtown (and beyond) teemed with workers typing on keyboards, printing copies, chatting with colleagues, and performing the usual tasks and rituals of a workday. Across the city, people filled stores and food courts at malls; crammed themselves onto subway trains and buses; dined at restaurants; drank at bars; laughed, cried and cheered at Broadway and movie theaters; packed Madison Square Garden and Barclays Center to see their favorite teams play; and gathered at households for the many parties, dinners and other festivities among family and friends with little care about distance or intimacy.

In short, life was normal — as New York City could define that word.

But on that fateful day last January, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the first case of novel coronavirus, COVID-19, in the United States, with a patient in Washington state. More than three thousand miles away from here, it was the first visible cloud in a storm heading for New York City that would forever alter our history.

Even with the best preparations made, no one could fathom how bad the storm would get in just two months — or how deadly it would be.

February: The Gathering Storm

The news prompted action from city and state officials to begin preparing for a possible pandemic. It seemed inevitable that the virus would make its way to New York; it was only a question of when.

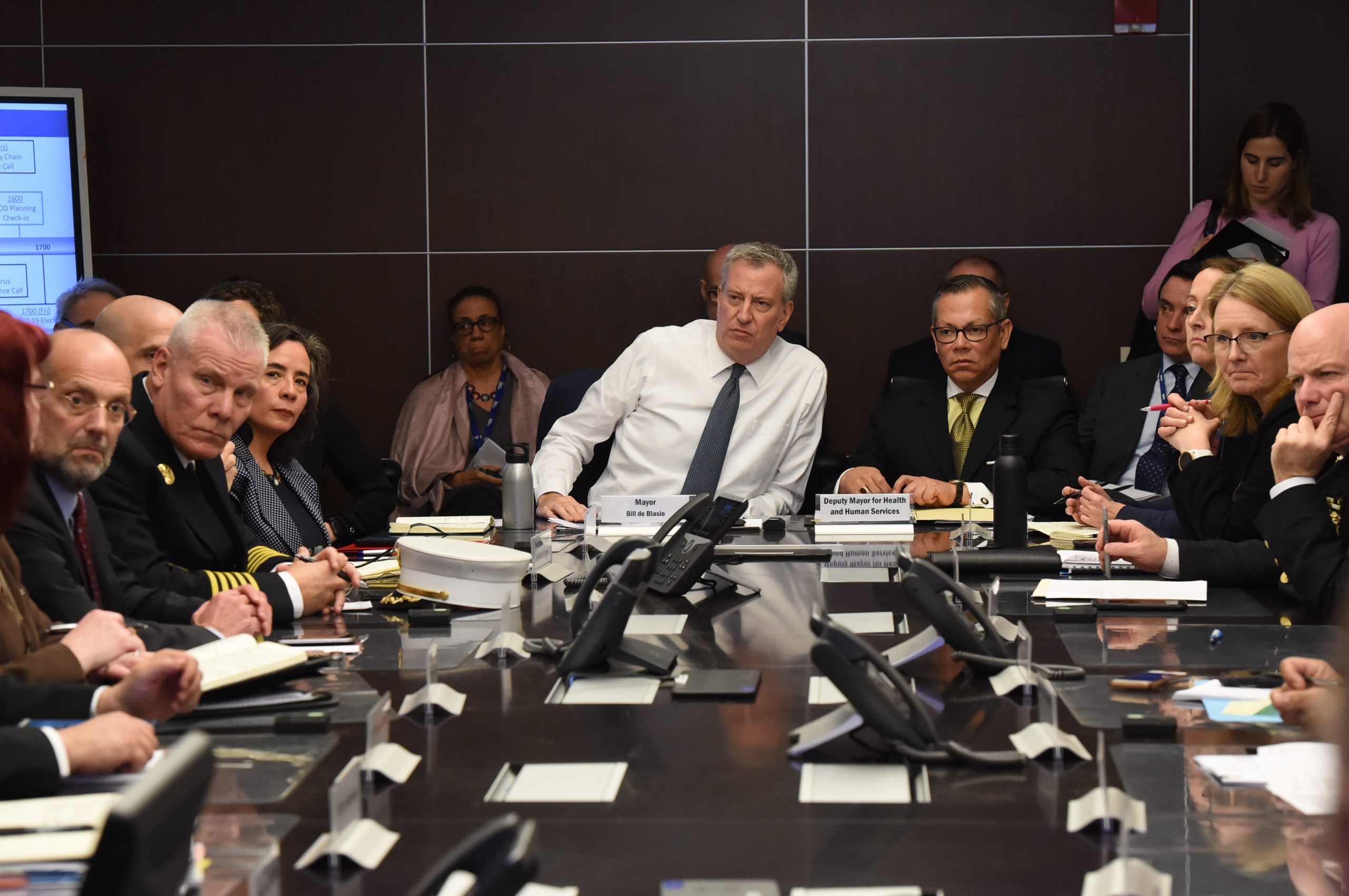

New York, which has seen all kinds of disasters and always plans for them, got to work. Three days after the first confirmed U.S. case was announced, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a preparedness plan for containing the virus whenever it officially arrived in New York. This included public guidance to wash hands, use hand sanitizer and stay home if they are sick — things that would become part of a oft-repeated mantra in the weeks ahead.

Because the COVID-19 outbreak emanated in Wuhan, China, the focus was primarily on New Yorkers who had recently traveled there and had returned to the city. But by early February, the highly-contagious virus had begun spreading around the world, including Europe.

The month saw several suspected coronavirus cases in New York City among patients who had become ill, and had recently traveled to infected areas of China. The tests, however, came back negative. That didn’t stop the growing concern over COVID-19 — nor did it prevent a troubling side effect: hatred.

The city’s Asian communities began suffering economically as visitors stayed away in a paranoid fear of the virus. Hate crimes against Asian New Yorkers also began to trend upward, especially after Trump and conspiracy theorists sought to assign blame to China over the outbreak with misinformation and ignorance.

As March approached, normal life in New York City continued humming even as the skies began to darken. The stock market began cratering, fueled primarily over fears of a global pandemic. News reports from China and Europe catalogued the horrors of the spreading illness, with pictures of teeming hospitals, mass death and widespread shutdowns beginning to show the true gravity of the crisis.

Finally, on March 1, 2020, the inevitable happened — the first confirmed coronavirus case in New York had been announced. Patient zero was a Manhattan woman who had come down with the illness following a recent trip to Iran, where COVID-19 had taken hold. Her symptoms were said to be mild in nature, and she would recover.

In all likelihood, however, the virus was believed to have arrived in New York weeks before the first case was detected. Though Trump had instituted a travel ban from China on Feb. 2, he did not stop flights from coming into the U.S. from other parts of the world, including areas of Europe that were being ravaged by COVID-19.

“The virus came from Europe,” Governor Andrew Cuomo would say, repeatedly, in the weeks and months after the pandemic took hold of New York. A study in April estimated that New York had 10,000 undetected COVID-19 cases as early as February 2020.

The cases would only go up from there through community spread, with fatal impact. No one could have imagined the variety of horrors New Yorkers would bear witness to over the next eight weeks.

And as the virus began to spread in early March, the unthinkable happened: The “city that never sleeps” became a ghost town.

March: Empty streets, packed hospitals

Because COVID-19 was a new virus, it was difficult for medical experts to determine how to treat those who became sick, or how to prevent others from becoming infected. The best advice, at the time, came down to washing hands, staying home if feeling ill, and avoiding large gatherings — aka “social distancing.”

As more knowledge about the virus came to the fore, New Yorkers would later be encouraged, then mandated via a governor’s executive order, to also wear masks out in public.

New Yorkers began panic buying; hand sanitizer, disinfectant, other cleaning supplies and even toilet paper were soon in short supply. Long lines were seen at supermarkets as people bought what they could to prepare for a long period at home. Offices began shifting workers to telecommuting, which began a rapid decline in mass transit ridership.

Private schools and colleges began closing their campuses and moving to remote learning. As of the week of March 9, the plan remained to keep New York City public schools open — but calls to shut them down intensified as COVID-19 continued to spread across the city.

Then, over a 48-hour period between March 11-12, ordinary life in New York City seemed to suddenly come to a crashing halt “out of an abundance of caution.”

The St. Patrick’s Day Parade scheduled for March 17, a 250-year tradition that drew millions of spectators each year, was cancelled for 2020. Other parades and street festivals across New York scheduled later in 2020 followed suit after their permits were canceled.

The NBA and NHL suspended all games indefinitely — emptying out Madison Square Garden and the Barclays Center — and MLB suspended spring training, leaving the Yankees’ and Mets’ seasons in doubt.

On March 12, Cuomo signed an executive order that banned all gatherings of 500 or more and dropped the maximum capacity of venues with less than 500 by 50%. Broadway went dark as a result. Cultural institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art also closed indefinitely.

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York and Diocese of Brooklyn took the extraordinary step of dispensing all obligations for Catholic New Yorkers to attend Sunday Mass.

The closure of city life continued into the following week. On March 15, the city finally announced a closure of public schools, with all classes cancelled for a week as teachers prepared for remote learning. The students would not return to the classroom until September.

Mayor de Blasio, on March 16, signed an emergency order that shut down all theaters and clubs, and severely restricted restaurant and bar operations. Essentially, eateries in New York City could only serve customers via delivery or takeout services.

Eventually, all non-essential workers in New York state — those who weren’t health care workers, utility workers, grocery store employees, or anyone responsible for keeping the basic necessities of life going in the five boroughs — were ordered to stay home after Cuomo put all non-essential activity on “PAUSE.”

Businesses across the city abandoned their offices and swiftly converted to telecommuting operations. Even the New York Stock Exchange moved all trading activity online — the heart of America’s economic power would remain void of day traders for months.

The social distancing orders and pause on non-essential economic activity came with disastrous consequences. Thousands of New Yorkers lost their jobs almost immediately; scores of businesses suspended operations or closed permanently.

In a society where so many were living paycheck-to-paycheck before the pandemic, people ran out of resources to pay their rents or put food on their tables. They would turn to charities in increasing numbers — and those in government began to realize they, too, would need to step up to help people survive the pandemic.

But despite the economic suffering in New York, the pandemic was about to take an even costlier turn — one that made dollars and cents practically meaningless.

In the next part of our COVID-19 retrospective, we’ll examine the grim days of late March and early April, when New York bore witness to the horrifying and deadly consequences of the virus.