BY DAVID SHENGOLD

Exceptional Massenet and Adès stagings in Santa Fe

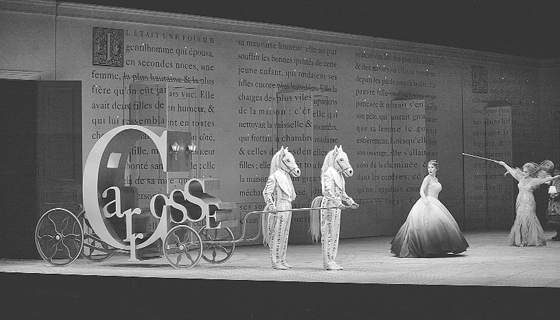

Laurent Pelly’s “Cendrillon” centered around Joyce DiDonato in the title role, with Eglise Guiterrez as the Fairy Godmother.

Opera-goers attend international festivals in the hopes of witnessing stagings like Laurent Pelly’s brilliant production of Massenet’s enchanting “Cendrillon” (August 9), centered around Joyce DiDonato’s vocally and theatrically incandescent heroine. Or the first North American staging of Thomas Adès’ 2004 “The Tempest” (August 11), thanks to a strong cast, director Jonathan Kent, and designer Paul Brown. Many factors make any Santa Fe Opera’s summer season memorable, not least the phenomenal beauty of the open-at-the-sides opera house—breathtakingly sited, truly invigorating. Not every opera presented is on this level; Tim Albery’s doggedly unmagical “Magic Flute” (August 8) offered some good performances, but scarcely attained festival standard.

Pelly’s typically supercharged comedy unfolded in Barbara de Limburg’s (literal) storybook sets, his costumes providing major laughs as well as character insight. But the work’s core of feeling also emerged, not least due to DiDonato’s wondrous ability to project sympathetic vulnerability. Her Cendrillon, boasting excellent French and gorgeous pellucid tone, must be seen in New York and richly merits preservation on DVD. Massenet made both lovers here high mezzos, giving them some of the most rapturously romantic music imaginable.

Jennifer Holloway, an apprentice artist, doesn’t show great individuality yet, but did a very fine job, looking and moving wonderfully as a despondent teenage Prince; her singing was secure and attractive. The fabulous Eglise Gutierrez (Fairy Godmother), not yet fully at home wedding French text to her sensuous, well-sculpted vocal lines, really hit her stride in Act II, when Massenet calls for truly astounding stratospheric feats which she made sound completely natural. Longtime company favorites Judith Forst (a riotous Mme. de la Haltière in looks and movement) and Richard Stilwell (Pandolfe) offered style and enduring range if not much timbral refulgence. Promising bass Riccardo L. Lugo (King) showed personality.

Pleasing, sometime historically allusive touches distinguish Massenet’s orchestration; Kenneth Montgomery really galvanized an orchestra that had sounded out-of-sorts under William Lacey for “Flute” the night before.

While “Flute” was sung in German, Albery saddled the cast (and audience) with his own painfully unfunny, flat dialog in variously accented shades of English, largely delivered with excusable lack of conviction. It often rhymed, as in Monostatos’ “He treats me badly—that isn’t right!/ I’m going to work for the Queen of the Night!” In fact, nothing about Monostatos was right—whinily vocalized by David Cangelosi, he was costumed as a Nazi gauleiter accompanied by storm troopers—any reason the dark-clad 18th century Enlightenment types at Sarastro’s court would tolerate and harbor these goons?

The Queen and her Ladies sported tiaras with pale, bulky Elizabethan dresses with ruffs. The Queen’s vital entrances and exits were perfunctorily staged; trapped in the dress, Heather Buck—whom I’ve seen elsewhere move like a supermodel—had to galumph, in profile, in and out the same door. Buck squarely hitting three of five high Fs, proved adequate where adequateness isn’t enough.

Meanwhile, Sarastro—the linguistically impossible, peculiar-techniqued Andrea Silvestrelli, loud but nasal and breathy—relaxed in a red nightgown. The undistinguished Speaker (John Stephens) sounded equally asthmatic and gray. Papageno was beautifully and forthrightly voiced by Joshua Hopkins, a Canadian baritone clearly destined for a fine career; his portrayal—decked in a T-shirt, yellow shoes, long jean shorts, and the now inevitable baseball cap—was gamely earnest.

Toby Spence (Tamino) and Natalie Dessay (Pamina) were the best of the cast, though costumed to evoke “Barefoot in the Park.” Spence made a convincing blond Prince Valiant, even if his overemphatic dialog suggested Orlando Bloom declaiming Tennyson; his singing is artful and attractive if rather monochrome. Dessay’s highly musical phrasing always compels interest—there was considerable beauty in the softer-edged parts of the role, but the touch of expansiveness that a Pamina ideally has in reserve was absent. As often she proved so anxious to display her girlishly agility that she barely stood still, seeming not remotely princess-like nor to derive from the world of this production’s Queen. Still, a worthwhile assumption.

In smaller roles, the most vocal excitement came from Dimitri Pittas and Joshua Bloom (Two Armed Men).

“The Tempest” has much music of high quality, some of it meriting the term “Britttenesque.” Adès’ third act prelude and canonic quintet are especially fine. Meredith Oakes’ text remains—seemingly deliberately—rather prosaic; one questions the presence of the chorus, though the writing for it was fine and well executed; having other women onstage pointedly dilutes the iconic status of Miranda (Patricia Risley, attractive if somewhat anonymous-timbred).

Kent staged a very effective show around Brown’s saffron sand dune and blasted, interlaced trees.

Rod Gilfry showed a return to vocal form as a strong Prospero with admirable diction. Most of Ariel sits above high C and Cyndia Sieden was genuinely astounding, meriting a huge ovation, as did William Ferguson, the affecting, clear-toned and expressive Caliban. Veterans Gwynne Howell (Gonzalo) and Chris Merritt (Alonso) gave moving, well-sung performances; Derek Taylor made an incisive, hot-blooded Antonio. Alan Gilbert led an excellent performance of this compelling, accomplished work.

Santa Fe’s other world-class musical organization, the Chamber Festival, offers many concerts every week. In the divinely daffy Lensic Theatre August 10 Anne Sofie von Otter joined Marc Neikrug and Gilbert (not dazzling) in Brahms’ “Two Songs.” In the second von Otter’s upper register shone, but the middle sounds rather recessed and one wonders about her plans to tackle Wagnerian roles. The most inspiring playing came from Zuill Bailey’s cello in the Kodaly’s wonderful Duo with violin and Jonathan Biss in the Third Brahms piano trio.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.

gaycitynews.com