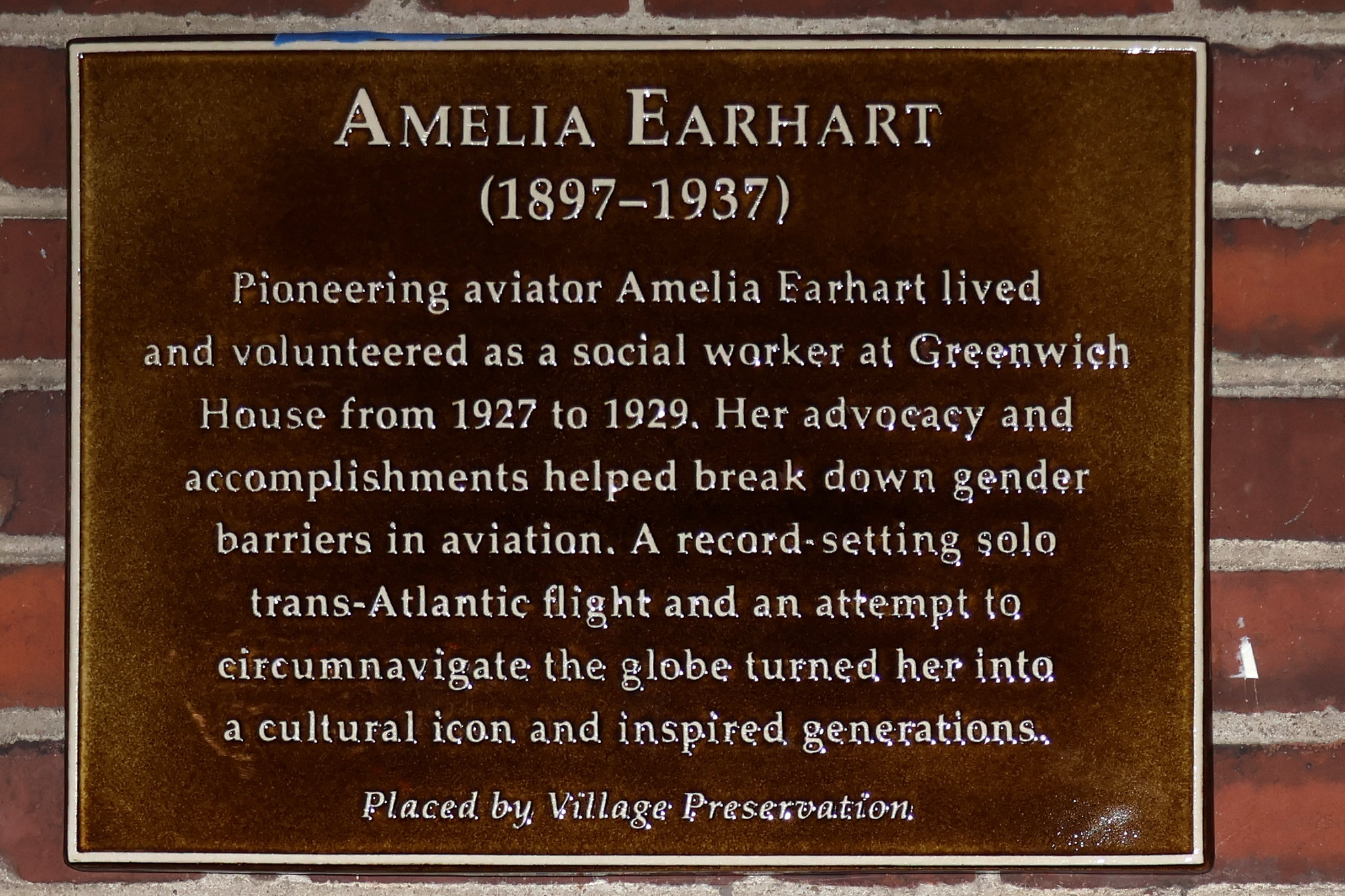

It took Amelia Earhart less than a full day to cross the Atlantic solo, breaking records, a glass ceiling (made of clouds) and inspiring many, but nearly a century later a plaque went up honoring her work and time in Greenwich Village.

Village Preservation on October 27 unveiled a plaque honoring “pioneer aviator” Amelia Earhart at Greenwich House, where she once lived and worked.

The plaque honors the famed female aviator or aviatrix who lived from 1897 to 1937 and was as a social worker at Greenwich House from 1927 to 1929.

In a city where the past is more honored in books than buildings, the plaque remembers her as an aviator whose “advocacy and accomplishments helped break down gender barriers in aviation.”

And it cites her “record-setting solo trans-Atlantic flight” and attempt to “circumnavigate the globe” that “turned her into a cultural icon and inspired generations.”

A commemorative U.S. postage stamp in 1967 honored the famous aviator, but this marks a local commemoration honoring her life, work and time in Greenwich Village, as part of many years in New York City.

“We’re thrilled to be able to honor and recognize the pioneering and trailblazing aviator Amelia Earhart, whose daring efforts inspired a generation,” said Andrew Berman, executive director of Village Preservation, a nonprofit dedicated to celebrating and preserving the history of Greenwich Village, East Village, and NoHo.

This is the 27th plaque Village Preservation unveiled in Greenwich Village, the East Village and NoHo as part of a program marking the homes of local figures and historic sites.

Plaques have gone up honoring local and national figures such as Jane Jacobs, James Baldwin, Allen Ginsberg, Charles Mingus, Frank O’Hara, Frank Stella, Martha Graham and Lorraine Hansberry.

They mark historically significant sites such as the former NAACP headquarters, Julius’ Bar, and the Fillmore East.

“Her entire ethos of breaking boundaries was shaped in large part by her experience in Greenwich Village,” Berman continued. “Honoring her with a plaque on her former home here feels particularly fitting.”

Born Amelia Mary Earhart in Atchison, Kansas, she is best known as an aviator, but Village Preservation in a post notes she shattered “a record-breaking 18,415-foot glass ceiling in her airplane.”

They praise her as a “staunch and vocal feminist, an author, a social service worker, a fashion icon, and, for a time, a Greenwich Village resident.

Earhart may be famous for her work in the sky, but on land, she also showed a sense of social mission and a desire to help.

She became a nurse’s aide in Toronto and in 1919 moved to New York to study medicine at Columbia University, before moving to California where her parents relocated in 1920.

It was there, in Long Beach, California, that she went on an airplane ride where she found both purpose and passion.

Earhart asked Anita “Neta” Snook, a pioneer aviatrix, for lessons, saying, according to Village Preservation, “I want to fly. Will you teach me?”

“Earhart was dedicated to expanding the role of women in our society,” Berman said. “That manifested not just in her own incredible feats, but opening the doors for and working with other women to get to the place where she achieved her greatness.”

In 1921, Earhart bought her first plane, earning her pilot’s license two years later before moving to Boston, where she became a social worker at the Denison House, a settlement home for immigrants.

She also became a sales representative for Kinner Aircraft in Boston before in 1927 moving to Greenwich Village and then becoming Aviation Editor at Cosmopolitan.

She lived and worked at Greenwich House, at their still-existing main building at 27 Barrow Street, from 1927-1929.

Charles LeBoutillier described her while she was “living in an apartment in the Village” in the “settlement house.”

“I think most of the people in the neighborhood knew who she was but nobody took much notice,” he said.

“Greenwich House, which was a transformative institution, shaped and reflected her values,” Berman said. “She wasn’t ‘just’ an aviator. She was invested in helping transform society.”

In 1929, Earhart helped found and became the first president of an organization of female pilots that became known as the Ninety-Nines. Earhart served as its first president.

Keeping her maiden name while married, she wrote to The New York Times, “reminding them to never call her Mrs. Putnam,” according to Village Preservation.

In 1928, she became the first woman to cross the Atlantic in a plane, although others piloted the craft.

She, in August of that year, became the first woman to fly solo across the North American continent and back

In 1931, Earhart married publisher George Palmer Putnam, who was also vice president of the Explorers Club, and they lived in an apartment at the Hotel Wyndham, 42 West Fifty-Eighth Street.

In 1932, she became the first woman to make a nonstop solo trans-Atlantic flight, earning a Distinguished Flying Cross.

“My ambition is to have this wonderful gift produce practical results for the future of commercial flying and for the women who may want to fly tomorrow’s planes,” Earhart said.

In 1937, she set out to fly around the world in a twin-engine Lockheed Electra, with Fred Noonan as her navigator for a 29,000-mile journey.

After traveling 22,000 miles over the central Pacific Ocean on their way to Howland Island, her plane’s signal vanished.

After a search-and-rescue mission, including U.S. Navy and Coast Guard ships and planes that scoured 250,000 square miles of ocean, they were unable to locate the plane and its occupants.

“It was tragic and mysterious,” Berman said. “None of us knows exactly what happened. She knew the risks involved and was not deterred by them.”

Earhart and her plane disappeared on July 2, 1937, after nearly 40 days, ending a life and career in which she took on progressively bigger challenges.

Researchers claim an underwater object near Nikumaroro Island, halfway between Australia and Hawaii, could be the plane that disappeared into the ocean.

They planned to examine the “Taraia Object” in early November as the search for the aircraft that disappeared into the ocean continues, but recently postponed the examination until next year.

“We want people to continue to be inspired by her life and legacy,” Berman said. “We want people to understand and appreciate the rich ferment of Greenwich Village in helping to create people like Amelia Earhart, James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansbury and Jane Jacobs and other people we honored with our plaque program from their neighborhood.”