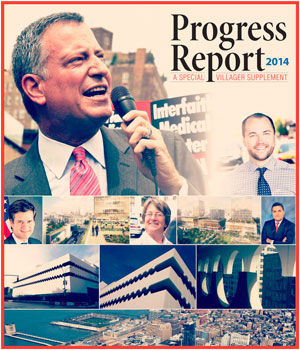

PHOTO BY TEQUILA MINSKY

BY ARTHUR Z. SCHWARTZ | We Villagers like to think of ourselves and our community as something exceptional. If fact, it was the only community in the city where constituents tried to declare an independent republic. (That was in 1917 for history buffs.)

And we have been, during the last 50 years, more successful than most communities at preserving our character — with a few glitches here and there. But we are not an island, and the larger political and societal setting plays a role in our ability to preserve the low-rise, people-friendly feeling that makes the Village such a wonderful place to live.

DISTRICT LEADER

The societal setting has taken the lead these past 40 years, as the desirability of our neighborhood has pushed up property values. A community once full of singers and dancers and opera singers who rented a “flat” for $100 per month has made way for 10,000-square-foot, single-family homes, and $4,500-per-month studio apartments. And Bleecker St.’s western end looks more like Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills than a bohemian mecca.

The societal setting has taken the lead these past 40 years, as the desirability of our neighborhood has pushed up property values. A community once full of singers and dancers and opera singers who rented a “flat” for $100 per month has made way for 10,000-square-foot, single-family homes, and $4,500-per-month studio apartments. And Bleecker St.’s western end looks more like Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills than a bohemian mecca.

The 1% (and the 2% through 5%) have flocked to the Village. At least they have respected our political leanings, voting for Barack Obama in 2008 (versus Hillary), Bill de Blasio in 2013, and even electing me as district leader despite my representation of Occupy Wall Street and my generally social democratic points of view.

But the mayor and the City Council leadership — the folks at the end of the land-use process in New York City, and of decisions on school funding and siting — can have a major impact. We have suffered some serious setbacks these past few years, with the loss of St. Vincent’s, its replacement with $3,500-per-square-foot condominiums, and the approval of the N.Y.U. and Chelsea Market expansion plans. Were it not for the dedicated push back led by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, we would have lost a lot more. (If we were a republic, I would nominate Andrew Berman for president.)

We had a mayor and a City Council speaker who never saw a development plan that they didn’t love, and it is pretty clear that the shape of our neighborhood will be greatly affected not just by what our new mayor, Bill de Blasio says, but by what he does.

Here is my hope. Bill de Blasio, though he spent years as a political operative, was also someone who ran for and served on a local school board. He lived (and lives) on a block with regular people in an integrated, middle-class neighborhood. His kids go to public school. He drives his own car, shovels his own snow, and goes to the supermarket (none of which our prior two mayors did.)

Both as a school board member and as a community activist, de Blasio understood the thought and passion that local people give to issues that affect their lives: land-use issues, parks, playgrounds, liquor licenses, school configuration. Members of school boards (now known as Community Education Councils), and community boards listen to dozens of people about issues, and debate them thoroughly before taking a position that they believe is both “the community’s decision” and a statement of what is best for their community.

Rudy Giuliani would listen — he actually had town hall meetings in every community board in the city — denounce those who disagreed with him or his staff, and then do what he wanted to do.

Bloomberg took things one step further. He made sure that all the public hearings were held — sometimes even transcribed — went through the process in a pro forma manner, and then did what he pleased. For example, tens of thousands of parents attended Board of Education hearings over the last five years. This was the period when Bloomberg embarked on his program of making all schools smaller and having multiple school administrations in one building, closing and reopening failing schools, and promoting the growth of charter schools.

Most often, the presence of Bloomberg’s Board of Education officials at the hearing was a tape recorder. Parents would then go, en masse, to school board meetings, become part of a crowd of thousands who would yell and scream at the board members, only to see them approve every proposal without discussion. Mayor Bloomberg never attended a public meeting of any sort at which he could be questioned.

My expectation is that under Mayor de Blasio, the public process will be RESPECTED, not just tolerated as a procedural requirement. RESPECTED means that the community’s views will have a presumption of being what the city will do unless the developer, bar owner or government bureaucrat can demonstrate convincingly why that decision is harmful or unlawful. In other words, the community would have a real voice on key issues, acting through their community boards and Community Education Councils. Getting RESPECT will mean that those endless nights at board hearings and meetings would have a meaningful purpose.

Listening also would mean that Mayor de Blasio, as the chief employer of more than 350,000 people, listened to his employees in making decisions. It would mean that he would instruct administrators, at all levels, to engage their workforce as people whose opinions mattered, and whose unions were looked at as something more than as the party to negotiate wage increases and medical benefits. Mayor de Blasio certainly talked this talk when he approached unions for support.

We have only had two months. Still, some alarm bells are going off. On Feb. 27 the schools chancellor, in a decision blessed by the mayor, allowed 36 of 49 school “co-locations” to go forward, including the placement of 16 charter schools in overcrowded public school buildings. (Two decisions concerning local schools, Murry Bergtraum and University Neighborhood high schools, were reversed, in the case of the former, stopping the expansion of Success Academy charter schools into School District 1.)

However, Eva Moskowitz, the $490,000-per-year head of Success Academy, switched on her well-oiled P.R. machine, sucked all the oxygen out of the room and made it seem like she had been attacked because three of her 10 proposed new schools weren’t going to go forward. The reality was that parents at 34 of those schools where plans were approved were angry because they had strongly opposed the proposals. Many had supported de Blasio because he promised to respect the role of parents in the process, and no one from the new Department of Education had spoken with them before the decision was announced. De Blasio had denounced the Bloomberg process as “abhorrent,” because of its disrespect for parent associations and Community Education Councils. Yet, the new mayor made these decisions without the local consultation he had promised.

For us in the Village, the filing of a notice of appeal by the city addressed to the N.Y.U. court decision was also disappointing. As a candidate, de Blasio had announced his opposition to the plan, at least in its initial form. While the city still has time to change its mind and not file an appeal brief, it could have dealt a critical blow to N.Y.U. by not filing the notice, since it is unclear that N.Y.U. can litigate, on its own, the question of park alienation if the city accepts the lower court ruling.

It would also be nice for those of us in the Village whose kids use Union Square Park to have the mayor reassess having a restaurant in the pavilion.

There are a lot of wrongs to right in this city, and there are a lot of people with a long list of expectations. Yes, de Blasio withdrew the stop-and-frisk appeal, and ordered the Department of Consumer Affairs to give longtime newsstand operator Jerry Delakas a license; but there is a tendency to have a small group at the top making key decisions without involvement of the affected communities.

We in the Village have a lot of concerns, and a lot of creative minds willing to contribute. The mayor has to figure out how to ask.

Schwartz is a labor and civil rights lawyer and the Village’s male Democratic district leader. He has a pending lawsuit, on behalf of parent groups, Public Advocate Letitia James and Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, challenging 41 school co-locations. He also represents several of the city’s largest unions, including the Transport Workers Union and the Civil Service Technical Guild.