BY YANNIC RACK | When members of Community Board 4 (CB4) drafted a letter to the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission in June 2013, urging it to designate the former Bayview Correctional Facility, it had almost been a year since the women’s prison was abandoned.

Located at 550 W. 20th St. (at 11th Ave.), the building was evacuated shortly before Superstorm Sandy hit New York in October 2012. Its inmates, sent to other prisons throughout the state, never returned. Bayview became another casualty of Governor Andrew Cuomo’s efforts to save money by closing costly and underutilized prisons.

With rapidly changing neighborhood and rising rents as a backdrop, CB4 was worried the building would be quickly sold by the state, with unwelcome consequences.

“Current development pressures in Chelsea will almost certainly result in demolition of the building and its replacement by new construction,” said the letter, signed by then-CB4 chair Corey Johnson (now a city councilmember representing District 3).

“It was voted on by the entire community board, but we just never heard anything back [from the Landmarks Preservation Commission],” said David Holowka, a member of CB4’s Land Use Committee who co-authored the request for evaluation.

“They didn’t dignify us with a response,” he recalled, when he spoke with Chelsea Now this week.

Now local residents and advocates are hoping the building’s unique architectural features will be protected a different way. Last week, the governor announced that the building would be redeveloped into the state’s first “Women’s Building,” with an eye on preservation of its history — as a prison and, before that, a YMCA for sailors and seamen.

The 100,000 square-foot space, located directly across from the Chelsea Piers sports complex, will be renovated by the NoVo Foundation and Goren Group. The former is entering a 50-year lease for the building, with a possible extension of another 49 years.

When it is completed in the next four to five years, the building will host a range of nonprofit women’s organizations, and will also include a restaurant, an art gallery, and some additional office space for other nonprofit tenants.

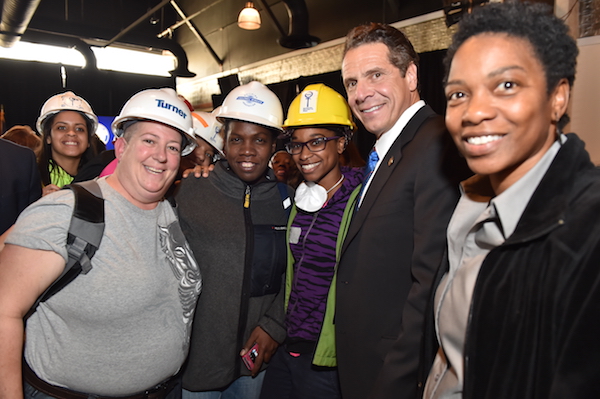

“Today we are continuing our efforts to shatter the glass ceiling by taking down an institution of defeat and turning it into opportunity and social reform for women,” Governor Cuomo said at an announcement of the sale, held Oct. 26 at Chelsea Piers. Also in attendance was writer, political activist, and feminist organizer Gloria Steinem.

Quoted in a press release issued that same day by the governor’s office, she recalled having “known personally since the mid-1970s…about the need and hope for a women’s building in New York City. Now, there is even more need because of high rent and operating costs here, and more hope because we’ve seen how much such buildings benefit other cities. New York has the greatest need because it receives so many women leaders from other states, other countries, other continents, yet they have no central place to visit — this building will unite them.”

According to that same press release, the plan was chosen through a competitive RFP (request for proposal) process by the Empire State Development Corporation, which took into consideration the wishes of the community for the site.

As a result, it sought a use that “preserves the building’s historic façade, provides opportunities for community facility use, and stays within the general zoning character of the Special West Chelsea District.”

That phrase is welcome news for those who pushed for landmarks designation, and also wanted the facility to stay a functioning part of the larger community.

“We’re happy not to see it become another anonymous luxury condominium that amounts to a fourth home for a billionaire who’s never even going to be present,” said Holowka. “They’re kind of constructing a wall of those between the community and the Hudson River.”

“I’m glad it is for nonprofit use, and I’m glad it’s neither a hotel nor luxury condominium, because we had a lot of requests for preservation and community usage,” said Christine Berthet, chair of CB4. “The rest will be dependent on the details.”

So far, there aren’t many. The building will house “a female adolescent wellness clinic and public atrium,” the press release says, but Pamela Shifman, executive director of the NoVo Foundation, said she couldn’t provide any more details yet.

“We’re going to be exploring these questions and many others in the time ahead. We were just granted the rights to the building last week,” she said in an interview.

“We are excited to be working closely with the community board now. We believe that The Women’s Building will be a really important community aspect, and is going to pull in the outside, and the Chelsea community to public facilities, lectures, conferences, performances, art shows, etc. I think our mission will definitely enrich the neighborhood.”

Shifman was equally vague on the details of which parts of the building might be preserved, emphasizing that they were still in the pre-development phase.

“We do know that we want to preserve key parts of the building to serve as a permanent reminder of what happened to women behind the walls of Bayview, and to educate everyone about what continues to happen to women in our criminal justice system,” Shifman said.

Holowka thinks the plan is a great idea, but added that the architecture worth preserving stems from the building’s use before it was turned into a prison in the late 1960s.

“The governor refers to it as an institution of defeat, with no reference whatsoever to the importance of the building to the neighborhood’s history — the working waterfront it represents and the history it embodies, which is pretty much written all over its façade,” he said.

The nine-story structure was originally built as a Seamen’s House YMCA in 1931 and served the sailors and merchant marine crews on the Chelsea waterfront. In addition to Art Deco massing and nautical-themed flourishes, the building’s brick façade also hides an indoor pool.

“This building was designed by the firm that designed the building that is most associated with New York City around the world: the Empire State Building. So it has an important architectural pedigree,” said Holowka, referring to architectural firm Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, whose signature skyscraper was finished in the same year as the YMCA.

“I’m happy that the governor has decided to put the building to what sounds like good use, but concerned at the wording of the preservation references,” echoed Pamela Wolff, a public member of CB4 and member of the West 200 Block Association.

She cited interior spaces like the swimming pool, adorned with aquatic mosaics, and a small chapel that sports a nautical wall mural and stained glass windows. The seafaring theme is evident in the brick exterior as well, which sports embellished terra cotta plaques and light fixtures.

Wolff has had ties to the building for a long time. Back when the state turned it into Bayview, she served on the Community Advisory Committee set up by the prison authorities to give local residents the chance to air any complaints and work out solutions for keeping the neighborhood safe.

“It lasted only briefly once people realized there wasn’t really a problem,” said Wolff. “The neighborhood [originally] had misgivings about the impact of the prison population on the community, but in reality there turned out to be none.”

In the end, she said local residents actually protested the closure of the prison because it had served an important community function, by keeping the incarcerated women close to their families and support structures, rather than shipping them upstate.

Now, with the burgeoning residential construction in the neighborhood, Wolff thinks there might be some of the same talk among the new population about The Women’s Building that had preceded the opening of the prison.

“What was purely waterfront use, and supporting businesses, is now high value condos on every side, with more to come,” she said. “Personally, I think having such a facility in Chelsea will be a great asset.”

Holowka also thinks the use is appropriate given the site’s history as a seamen’s house.

“It was meant to help ordinary people. And it looks like it will continue to be, and I think that’s just terrific,” he said. “What we’re mainly lamenting in Chelsea is the loss of community building blocks, and this will ensure that the building remains functioning as a social support cornerstone of the community.”

Shifman agrees, adding that the NoVo Foundation is committed to being good neighbors. As a sign of goodwill, residents can even submit their own ideas for community uses on a dedicated website for The Women’s Building (womensbuildingnyc.org), and Shifman added that there will be a series of public consultations held at the end of November, “so that folks in Chelsea or beyond who want to contribute their ideas and want to hear more can participate in these conversations.”

She also emphasized how the building would continue the mission of its first incarnation, rather than the most recent one.

“When the building opened in 1931 as a YMCA it did stand for values of safe harbor, community and hope,” Shifman said. “And in so many ways, The Women’s Building will have a chance to return to those same values.”