By Deborah Lynn Blumberg

In the heart of Chinatown last Saturday morning I sat meditating in the lotus position under a tree in Sara Delano Roosevelt Park. Around me birds chirped and groups of middle-aged Chinese men gathered on park benches chattered in Chinese.

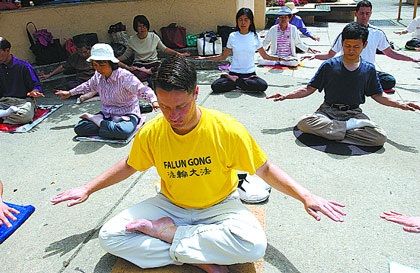

After two hours of practicing Falun Gong with New York practitioner Carsten Bornemann and his students, all the tension had left my body and I felt well on my way to reaching the increased energy levels and calm state of mind that proponents say this age-old Chinese practice can generate.

Deemed an “evil cult” and banned by the Chinese government, Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, is ancient form of qigong, the Chinese practice of refining the mind and body through specific exercises and meditation. In China, practitioners have been imprisoned and tortured for organizing and participating in classes, according to the nonprofit Human Rights Watch organization.

Falun Gong also emphasizes the importance of improving one’s moral character, but is not a religion. Over the past few years, the practice has grown in popularity, and founder Li Hongzhi says it now attracts tens of millions of people in over 40 countries — people like Bornemann who is native to Germany but now works as a computer consultant in New York.

After watching a PBS special that showed New Yorkers stretching and mediating in Central Park, Bornemann decided to try Falun Gong for himself. Now, three years later, he leads free classes each weekend in Sara Delano Roosevelt Park and in Central Park during the week. On Saturday a handful of students attend, and on Sundays the group can reach as many as 30 participants.

“Falun Gong was pushed into the public eye because of the persecution,” Bornemann said. “It’s an exercise you can do every day and it’s helped me to become calmer — at work, with people on the subway.” Bornemann also applauds the practice’s physical effects, adding that the stretching exercises and poses have toned his muscles more than 12 years of lifting weights at the gym did.

The two-hour long weekend classes open with a series of stretches called “Buddha Showing a Thousand Hands.” Bornemann instructed the group to stand with feet shoulder length apart, knees slightly bent and lips lightly closed with a relaxed and pleasant expression on our faces, a position we would hold for the next few hours. We gently stretched our arms, extending them out to our sides and then above our heads in flowing movements. The goal of this first exercise is to open energy channels in the body, Bornemann said.

We then moved into the next exercise, “Falun Standing Stance,” during which we held our arms in a series of four poses for several minutes — a simple concept, but much more difficult than I initially imagined. Holding your arms completely still above your head for 15-20 consecutive minutes is not an easy task.

My muscles soon began to burn and I prayed our time would soon be up. I focused on the chiming meditation music coming from Bornemann’s small boom box, and admired the more experienced students around me who held the poses for seven or more minutes each. This pose was an exercise in mind over matter designed to enhance energy levels and “awaken wisdom.”

Bornemann said that the exercise is also a good example of why Falun Gong is best practiced in groups — people encourage each other to hold poses and not give in to the pain. “If there’s a 98-year-old man next to me doing it, I know I can do it,” he said.

During the third part of the class, “Penetrating the Two Cosmic Extremes,” we circled our arms above our heads and across our bodies in gentle flowing movements, and for the fourth segment traced our hands across the entire body in an exercise known as “Falun Heavenly Circulation.” After completing the fourth exercise my body felt relaxed and my mind more focused, calm and free of pointless thoughts. These few hours in the park were perhaps the longest amount of time I had stood still in one spot for years, and it felt good.

The more advanced classmates moved at their own pace, and left as soon as they finished the series of exercises. One student, Kyoko Bata, and I remained and moved onto the grass underneath a tree for the 20-minute meditation that would close the session.

Bata, who was born in Japan but has lived in New York for the past 20 years, works as a translator and said she sits at a computer all day. When she told a friend she was looking for a low-impact exercise, her friend recommended Falun Gong. Bata now comes from her apartment on the Upper West Side each Saturday and Sunday to join the group.

“This is my activity, my time,” she said. “I have a husband and a child, but if they want to do it they have to go somewhere else,” she added with a laugh.

We sat on mats on the grass and Bornemann led us through the meditation, adjusting our arms to the correct pose and position. Afterwards, everyone would join for lunch in Chinatown at one of the group’s 10 regular lunch spots, often letting one Chinese classmate order off the Chinese-only menu for the entire group.

Ten minutes into the meditation, I knew the class was almost over and thoughts of shopping lists, dinner plans and even the opening line for this article flooded my mind. But like Bornemann said, even a small effort helps. “It’s very hard to quiet the mind,” he said. “Every little step is a great success.”