[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

- “Miro Rames”

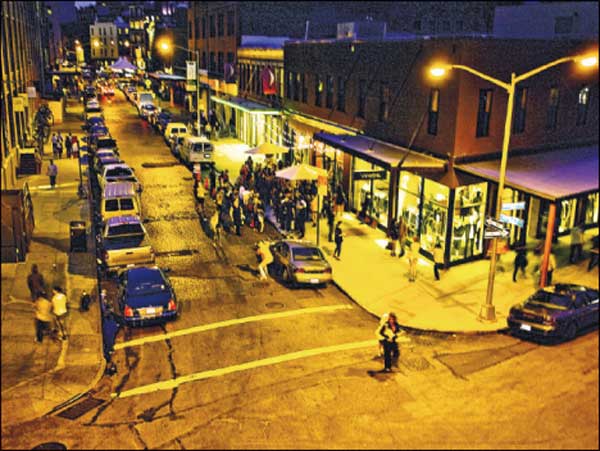

BY SCOTT STIFFLER | Like an enduring red stain on a white butcher’s coat, the 124 photos from Pamela Greene’s wry look at nine years in the evolving life of the Meatpacking District settle into your head and remain stubbornly lodged there. It’s not an unpleasant sensation — although the sights aren’t what you might expect from a collection of images taken during the decline of one industry and the rise of another.

Rather than mourn the loss of longtime establishments or praise the area’s rapid ascension as a fashion hub, Greene’s body of work (shot from 2002-2011) instead succumbs to the wonder of a neighborhood that lives and dies every 24 hours — then does it all over again.

An embedded witness to the daily changing of the guard from retail glory to nightlife glamour to industrial grit, Greene’s insightful framing and chronological storytelling extracts common elements shared by meatpacking workers, models, restaurateurs, clubgoers and prostitutes. All possess a similar devotion to routine, but only some are aware (and care) that their days are clearly numbered.

Given the fact that so many dynamic worlds collide within this relatively small patch of Manhattan, it would have been easy for Greene to simply pursue moments when all those disparate elements could be jammed into one busy shot. Instead, she wisely plays her juxtaposition card by way of the layout. The naked slabs of meat in “Hanging Hoofers” (on page 116) are complemented, just to the right, by page 117’s “Coats” (white butcher’s long coats dangling from their own miniature version of the same hooks lodged firmly in those aforementioned hoofers).

Greene’s left/right study in contrast gets a similar workout when page 30’s “Shadows and Light” shows construction workers unceremoniously emptying a garbage can — while, on page 31, “Tourists” has a couple consulting their map as a companion busily chats on his cell. This method provides a much more effective window into the changing times than what would have been achieved if Greene strained to make a single photograph do that job.

“A model going up the street, trying to dodge a side of beef? You didn’t really see that,” Greene maintains — noting that in reality, it was the photographer who often found herself yielding ground to the Meatpacking District’s most enduring product. “I was flat against the wall,” she says of the process that gave “Blood & Beauty” its cover shot. “You didn’t have to tell me not to move. I mean, you don’t want to run into a side of beef. That’s six hundred pounds. You’d be a goner.”

Considering all the people she did run into (and all the cows she managed to avoid), Greene emerged remarkably unscathed — but not unchanged. “It was personal by then,” she says, pinpointing a time in 2003 when she realized, “I wanted to do a book, a long-term project. I got to go deep, and understand the people — not the neighborhood. I wasn’t interested in the political science of it,” says the former poli-sci major without the slightest desire to shade that comment with irony. “I wanted to know the people. Although there were times when I took a month or so off, I completely immersed myself.” Greene, who’s been working for some time now on an “immigration project,” declares she’s not yet sure where that effort will lead — except to say, “I really am much happier when I’m working on a project that takes all of my time.”

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

- “Fashion Fun”

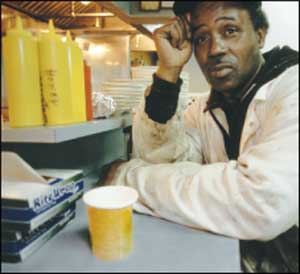

What Greene found in the Meatpacking District was a hive of subcultures — most of which were in the throes of collapsing or bursting. “People adapt,” Greene says admiringly. Referring to the meatpacking workers, she notes, “The key people I photographed are still around…but they’re working on the real edges of the district.” Of James Rogers (see his photo in this article: “James at Hector’s”), Greene recalls, “I took a lot of pictures of him. He told me he was very proud of his years in the Meatpacking District, and put his pension on hold so he could work as a freelancer. He knew that eventually, all of these plants would probably go.”

Greene doesn’t cast the fashion industry in the role of encroaching villain (in fact, she praises its pioneer spirit). Nonetheless, she recalls how meatpacking workers like Rogers viewed the new arrivals. “As soon as they heard [Diane] Von Furstenberg was going to move her world headquarters to Washington and 14th, they knew that virtually everything was going to be renovated, and they’d have to move. No question about it. One group was leaving — and they made their whole lives in that neighborhood.”

BLOOD & BEAUTY: MANHATTAN’S MEATPACKING DISTRICT

By Pamela Greene

Published by Schiffer Publishing Ltd. (2011)

$34.99

Visit schifferbooks.com and

pamelagreenephotography.com