BY JERRY TALLMER

Living Theatre continues tradition of mixing actors, audience

On the lam.

Take a powder.

Duke it out.

You better not be jerkin’ me around.

I’m gonna put you away for good.

Dig it.

I’ve got the goods.

You dirty…

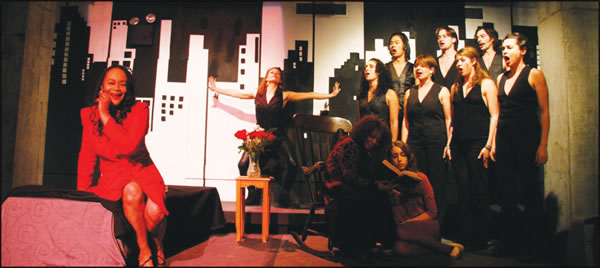

It isn’t every day in the year — any year since 1947, when Judith Malina and Julian Beck gave birth to their Living Theatre in an Upper West Side apartment — that you could hear such gangsterish language in their temple of breakthrough drama. But now you can hear those epithets in a play by Anne Waldman called “Red Noir” — which has been extended several times by popular demand. It’s set to run through February 27 at the Living Theatre’s latest locale, on the Lower East Side’s Clinton Street. Red Noir? All movie buffs know what Noir means. It means black, it means dark, but cinematically it also — particularly in this country and France — means a certain kind of low-budget menace-laden studio product, starring people like Robert Mitchum or Dick Powell, with unpredicted long-lasting cultural impact. Bur Red? Is it just as simple as it sounds, Judith? Revolution and all that?

Contemplating the fairy tale mountain she had just ordered — Belgian waffles, topped by chocolate ice cream, topped by a huge glob of whipped cream — tiny, fiery Judith Malina, in her 83rd year, raised her clenched right fist into the air. That said it all. Yes, revolution. To which she now vocally added a chant often delivered throughout Anne Waldman’s play: “Anarchy! Anarchy! Anarchy!”

Judith isn’t acting in this one. But she’s directed it, adapted it (side by side with the playwright), cast it, and done everything else possible to get it up there and working. Everything else includes, as usual, getting the audience into the action. The customers have little choice once their wooden folding chairs are stolen from under them by the actors. “We like to get the audience involved,” says Judith; and those “Livings” sure do — all the way back to Jack Gelber’s “The Connection” in 1959, where the actors mingled with the onlookers; and again with 1968’s “Paradise Now” — where Professor Richard Scheckner stood naked on his seat in a Brooklyn Academy of Music so wreathed in marijuana fumes that dear old Edith Oliver of The New Yorker said to me grimly: “Now I know why I’m voting for Hubert Humphrey!” Actually, says Ms. Malina, the Living Theatre did what she calls “free flow” between actors and audience many times before “The Connection.”

“It all comes from Piscator,” she says — Erwin Piscator (1893-1966), who taught drama at the New School for Social Research, on West 12th Street. Judith herself was one of his students from 1945 to 1947. “He was very hot for mixing actors and audience. Epic theater.” When push came to shove, says Judith, there were three people who changed all American theater: “Stella Adler, Herbert Berghof, and Lee Strasberg. And they all came out of Piscator’s school.” “Red Noir” is a first play by Anne Waldman, who has given birth to no fewer than 40 books of poetry. And of course there is some poetry of hers in this production.

“She was the best of the Beat Generation,” says Judith. “There was Kerouac and there was Allen [Ginsberg], and then there was Anne. I’d never worked with her. I read the printed version of the play a couple of years ago, and immediately wanted to do it. We sat down side by side and spent hours going over the whole thing word by word.” A couple of words that somehow snuck in are “Clinton” and “Street” — where the Living Theatre now resides.

“Anne was totally enthusiastic. Just yesterday she put a new line in.”

The show opens with a tribute to revolutionist Emma Goldman (of Stanton Street), just to let you know where its heart is, and is peppered all the way through with wonderful anarchist battle cries like “No leaders are good leaders,” “There is no God,” “Revolution is revelation,” and, for a change of pace, “Better no heart than a heart of Paprika.” One strand of “Red Noir” is woven by Beatrice (wonderful Vinie Burrows), an elderly black woman who sits reading to the 11-year-old white girlchild at her feet (Camille de Aranja) from the autobiography of emancipation’s Frederick Douglass. Grandma Beatrice also sings a new kind of spiritual, “Reach Out to Haiti.” Douglass never knew his own age because slaves (and their offspring) were not permitted to know such things.

A second strand is pursued by Ruby (no less wonderful Sheila Dabney), a glamorous detective who is in fact pursuing two shadowy guys that are skedaddling with two identical suitcases — one loaded with a ticking nuclear device to destroy the world, the other with seeds to restart the world. There is also a running man named Bolt (Eno Edet) — “a scientist with nimble feet” — on the Runaround track that surrounds the stage, and a girl named Crystal (Judi Rymer) whose form of protest is to lie down naked in front of supermarkets — much to the disdain of older sister Ruby. “A destructive suitcase and a constructive suitcase,” says Judith.

And then — well, then there are the movies, or at any rate movie clips — of Cagney, Bogart, and Edward G. Robinson firing guns against the background of a “Horrors of War” pastiche by Eric Olson. The original play had only six characters. “I like to have a lot of actors,” says Judith, “so I added a twenty-five person anarchist chorus; beautiful, intelligent young people” — and one or two veterans like Tom Walker, now in his fifteenth season with “The Livings.” “I compare him to Mickey Mantle,” says Judith’s young aide-de-camp, Brad Burgess.

So, Judith, Julian is gone and Hanon Reznikov is gone — the two men in your life, if we don’t count your father the Kiel, Germany, rabbi — or your son Garrick. Meanwhile, as you’ve pointed out, you’re still here. What’s next? “I’ve finally read the Bible,” said Judith Malina.

Don’t think she won’t make something out of that material.