BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | After three weeks of assistant district attorneys presenting the case against Pedro Hernandez in the 1979 disappearance of Etan Patz, the prosecution rested last Friday. On Monday, the defense began presenting its case.

It’s expected the historic trial will wrap up sometime in mid-April.

Although Hernandez confessed to police nearly three years ago that he killed Patz, his defense team says this was coerced under pressure and that he is mentally ill and hallucinates.

Last Friday, the prosecution presented a forensic video made by the District Attorney’s Office that retraced the 6-year-old Soho boy’s planned two-block route from his Prince St. loft to his school bus stop, two blocks away on West Broadway. The video pauses to film the bodega at the northwest corner of Prince and West Broadway where prosecutors say Hernandez was working at the time Patz vanished.

Hernandez reportedly was, in fact, at that time living right across the street in an apartment on the intersection’s southwest corner with his sister and her husband, Juan Santana. Santana ran the bodega and was its cashier. Now a super for a number of Soho buildings, he reportedly still lives in the same place.

The D.A.’s video then continues one block further down Prince St. — crossing midway down the block from the north sidewalk to the south sidewalk, then going down a stairway at 113 Thompson St., then through a long, narrow alleyway and into a courtyard. Hernandez had previously taken detectives on this path, claiming it was where he dumped the young boy’s body after strangling him in the bodega’s basement.

However, Harvey Fishbein, Hernandez’s lead defense attorney, has previously stated in court that in 1979 a door that was in front of that alley opened directly into a bakery.

Last Friday, the prosecution also presented four recorded phone calls between Hernandez and his wife while he was in Rikers awaiting trial.

The prosecution played the calls aloud for the jury to try to demonstrate Hernandez’s “controlling” nature and that he, in fact, is mentally competent.

In one of the phone calls, Hernandez, speaking in a high-pitched voice, is disapproving of his 24-year-old daughter’s going out with a friend to Great Adventure, fearing she might drink alcohol there. He also demonstrates that he is keeping a careful tally of the money he has left to make phone calls, and urges his wife to add more dollars — in the allowable $25 increments — to his prison phone budget.

This grasp of basic math, the prosecution argues, clearly shows that Hernandez is not mentally incapable, despite having a very low I.Q. of only 70.

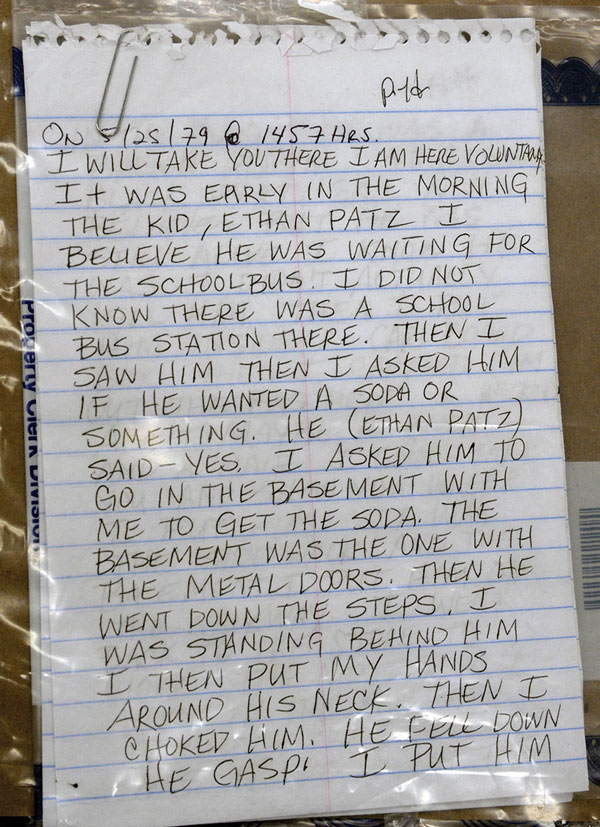

In addition, the prosecution called Dr. Michele Slone, the Manhattan deputy chief medical examiner, to the stand, and then played a videotaped confession by Hernandez in which he describes to detectives how he allegedly strangled Patz from behind.

In the video, Hernandez claims he somehow couldn’t help himself from choking the boy.

“Something took over me and I said, ‘This is more and more,’ and then he went like this,” he said, shrugging to show how Patz’s body and arms allegedly went limp. He said the boy then fell down to the ground, though still gasping.

“Even though he was still alive, I put him in a bag, a plastic bag,” he said.

He said he then tied the bag, put it in a box and carried it out of the bodega’s basement on his shoulder.

As to whether anything sexual may have happened — assuming Hernandez really did encounter Patz on that fateful day — Hernandez did say something to detectives during his confession after his arrest in New Jersey in May 2012. A detective testified in court that Hernandez, during his confession, at one point, unsolicited by his interrogators, stated, “But nothing happened sexually.”

Hernandez, over the years, had claimed to relatives and church group members that he had killed a boy.

Subsequent to his confession, though, in December 2012, Hernandez pleaded not guilty to charges of murder and kidnapping.

Stan Patz, Etan’s father, sat in court last Friday, as he has every day of the trial from its start.

The Patzes long believed that Etan was killed by Jose Ramos, a homeless character who used to hang around Soho and was the boyfriend of the Patzes’ babysitter. Ramos has served two decades in prison on child-molestation charges unrelated to the Patz case.

Etan was declared legally dead in 2001. The Patzes filed a civil suit against Ramos, resulting in his being declared legally responsible for Etan’s death in 2004.

The defense has been expected to argue that Ramos, not Hernandez, killed Etan.

Adding to questions about Hernandez’s mental state, this week a forensic psychiatrist testified that Hernandez told him he had seen an assortment of bizarre people there with him in the basement at the same time as he allegedly killed the boy.

Asked for comment by The Villager last Friday during the jury’s lunch break, Stan Patz declined, as the family has largely done with all media in recent years. He quietly walked down the hall past a battery of news photographers that are stationed there every day to get shots on the ongoing story, one of the world’s most infamous missing-child cases.

Bill Dobbs, a Soho resident active in peace, civil rights and gay rights issues, was in the audience in court last Friday. He has been attending the trial as often as he can.

“My fascination with this case is because I moved to Soho three years after [Etan vanished], and because this completely turned American childhood upside down,” he told The Villager.

In a phone interview, Sean Sweeney, director of the Soho Alliance, said he has seen Santana, Hernandez’s brother-in-law, around the neighborhood for years, though has never spoken to him. No one seems to recall Hernandez, though.

“He had a son whom I would see around the area, who likely was about Etan’s age, until he left about 20 years ago to join the military and I think now lives in Queens, a decent kid,” Sweeney said of Santana.

As for the bodega, now long gone, Sweeney recalled, “It was a real bodega. Hipsters and newcomers call any neighborhood grocery store nowadays a ‘bodega.’ It was run by the Puerto Ricans who lived in the neighborhood, and it had just the basics. There would always be a couple of Hispanic guys hanging around, talking and occasionally drinking spirits out of little paper cups. I think at Christmas time they would offer free shots to people.”

The place was kind of run-down, but he noted, “It sold basics, and before Dean & DeLuca arrived, we needed something like that.”

Sweeney is also a longtime former president of the Downtown Independent Democrats. Stan Patz used to attend D.I.D. meetings to get the political club’s support for putting pressure on former D.A. Robert Morgenthau to pursue charges against Ramos. But Morgenthau felt there was insufficient evidence.

When Cy Vance ran for district attorney, however, activist Dobbs noted, he pledged to reopen the Etan Patz case.