BY PENNY ARCADE, DANA DAVISON and MIKKI MAHER | A suffocating and corrupt bureaucracy has grown up around social services for the elderly. Guardians, social workers, financial managers and other caregivers too often show a cavalier disregard for the welfare of their charges. And don’t imagine for a moment that it is only lonely, friendless, isolated denizens that become victims of abuse. If you are a senior caught in this bureaucratic quagmire, even your best friends can’t help you.

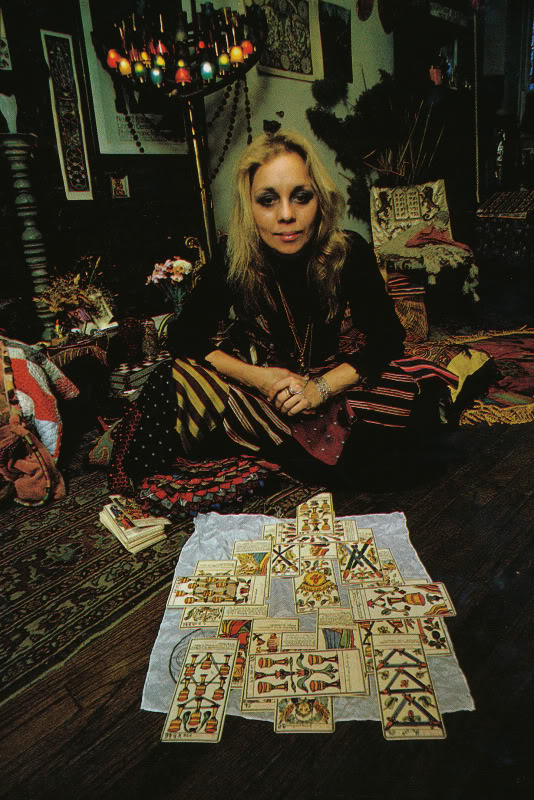

Consider the case of Kasoundra Kasoundra. This very original New York Underground personality, now pushing 80, has been an avant-garde artist for more than half a century. When she arrived in Manhattan as a Midwestern college dropout in the early ’60s, she boldly knocked on the doors of celebrities such as Hermione Gingold and Bob Dylan simply to find out what made them tick.

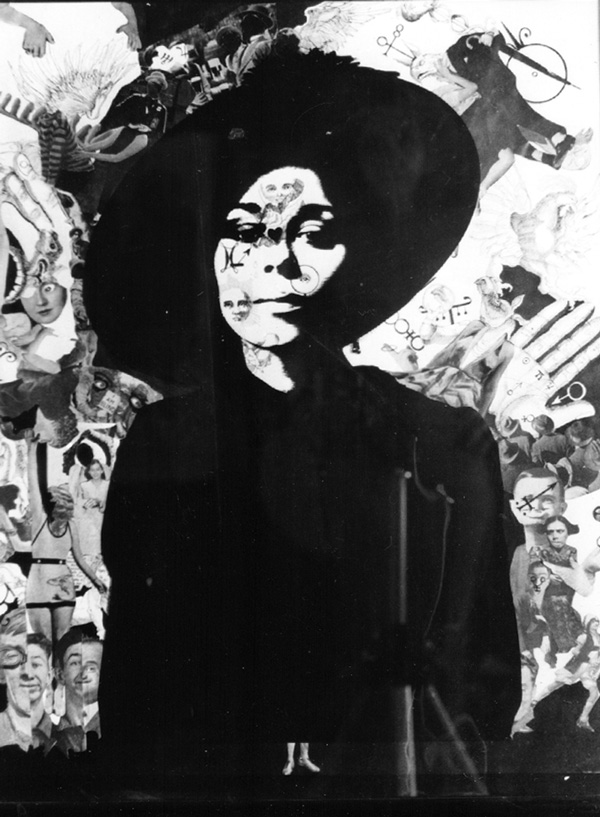

Modeling at the Art Students League to earn her living, Kasoundra inserted herself into the urban art underground, making friends with its creative geniuses while she perfected her own considerable talents as a witty collage artist. Brice Marden and Jonas Mekas, among others, collected her artworks, and Maurice Gerodias, founder of The Olympia Press, took her with him on trips to Europe.

Kasoundra hung out with the Alice’s Restaurant crowd at the church in the Berkshires, and acted in Harry Smith’s “Mahagonny.” Her poster of Harry looking at himself in his own eyeglasses is a sought-after treasure.

Flash-forward to January 2011, when Kasoundra was discovered lying on the floor of her kitchen and transported to Lenox Hill Hospital by Adult Protective Services. Kasoundra’s boyfriend had run off with her roommate, and despite her bad liver, Kasoundra had consumed an entire quart of vodka. When her friends finally located her in the hospital, she was yellow with jaundice.

The physically feisty Kasoundra bounced back soon enough, but she was transferred to the hospital’s psych ward because she complained of depression. This proved to be a dangerous disclosure, because from that moment forward, Kasoundra was never to enjoy her freedom again.

Although she has fought valiantly through three years of court hearings with three successive judges, Kasoundra remains marooned in a nursing home in New Rochelle with little hope of ever regaining her liberty. How could this happen?

Kasoundra’s trials began with her landlord. As she stayed in the psych ward month after month, her rent fell increasingly behind, and the landlord sued for eviction. Kasoundra paid him $2,000 as a gesture of good faith until she could return home and get her affairs in order, but the landlord was not appeased and the eviction proceeding continued.

Kasoundra had lived for 30 years in a rent-stabilized apartment on the Upper East Side, and under SCRIE (Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption) she paid $684 a month. With a modest renovation, Kasoundra’s four-room apartment —particularly in view of the new Second Ave. subway line — might easily fetch $3,500 per month in today’s inflated real estate market. Such apartments have become valuable assets to landlords, who often pay rent-stabilized tenants thousands of dollars to move out.

Although the hospital helped Kasoundra acquire a pro bono lawyer to stave off her eviction proceeding, the better course might have been to help her set up an automated bill payment plan at her bank so her rent could be paid on a timely basis.

Kasoundra’s next problem was that her medical condition, hepatic encephalopathy, caused her liver function to wax and wane. This condition (and/or the medication taken for it) can cause symptoms of grogginess and occasional forgetfulness — side effects that dissipate once the liver returns to normal and the medication is discontinued.

In the meantime, the psych ward social worker was reluctant to send Kasoundra home to her apartment, a three-flight walk-up. The staff considered that she might be better off living in Lott House, an elegant, assisted-living facility in her neighborhood, where she could occupy a studio apartment and have her meals served in the spacious dining room with windows overlooking Central Park. Kasoundra loved the park, and had once been a volunteer gardener there.

An appointment was made for a visit to Lott House, but after Kasoundra’s initial interview, her social worker sat on the application for months. No one helped Kasoundra apply for “Community Medicaid,” which, in view of her meager Social Security income, would be needed to pay for homecare services or for her residency at Lott House. Instead, the hospital applied for and received a “hospital Medicaid” payment for the hefty bill Kasoundra now owed the hospital.

As the year drew to a close, Kasoundra’s social worker, who was about to retire, was under pressure to dispose of her cases. Because Community Medicaid had not been set up, Kasoundra could neither return home nor move into Lott House, and her social worker decided to dispense with the problem by seeking a court-appointed guardian under Article 81. For this purpose, Kasoundra was given the short form of the R-Bans Mental Status Test, and the social worker said afterward that Kasoundra had performed poorly “on one component of the test.”

On this flimsy basis, the hospital applied to the New York State Supreme Court for a court-appointed guardian. Since Kasoundra had been adopted and her adoptive parents had passed away, she had no one who could intercede on her behalf or halt the impending termination of her rights and ability to control her own destiny.

The first guardianship hearing took place in December 2011. Although Kasoundra was never sent court papers (a procedural violation), she asked one of her friends to inform the judge’s clerk that she wanted a “trial by jury,” and that she did not want the “court evaluator” to have access to her medical records, if the evaluator was going to base a competency judgment on the results of the paltry mental status test. Kasoundra was legally entitled to both of these options, but her requests were ignored.

At the hearing, one of Kasoundra’s friends offered to become her guardian, but the social worker spoke out against this prospect, and the judge decided to appoint a professional guardianship agency.

Ironically, just before the hearing took place, Kasoundra’s latest liver test had come back “negative,” which meant that her medication would be discontinued and her sporadic grogginess would soon dissipate, which it subsequently did. But no doctor or social worker from the hospital brought up the results of Kasoundra’s latest liver test –– or its import –– at the hearing.

In her ruling, Judge Visitacion-Lewis stipulated that Kasoundra should be returned home with appropriate homecare services provided, or, if that proved too difficult because of the stairs, Kasoundra should be placed in an assisted-living facility “in her community.” (Since Lott House was the only such facility that accepted Medicaid, it was not only the most desirable but also the only option.) The judge also stipulated that the guardian should confer on all important matters with Kasoundra and work closely with her friends to insure that her needs were met. None of the judge’s directives were followed.

Kasoundra’s third problem was her guardian, Judah Samet of United Guardianship Services. Ignoring the judge’s orders, he promptly whisked Kasoundra to a nursing home in New Rochelle — far from her community and friends. Kasoundra was confined to a bed with a loud buzzer that went off every time she tried to get out of bed. She received no physical exercise, and soon her leg muscles began to atrophy. Even after her friends discovered where she was, they were unable to contact her because she had no working telephone. She remained isolated and alone for months.

Finally one of her friends brought a psychiatrist to the nursing home to evaluate Kasoundra. He gave her a routine mental status test and determined that her cognitive functioning was normal. He saw no reason why she should not live at home if she wished to do so.

But when this good news was communicated to the guardian, Samet said he was giving up Kasoundra’s apartment, and if her friends tried to interfere, he would take out an order of protection to prevent them from ever seeing Kasoundra again. He made no appointments for her at Lott House and, in fact, Kasoundra was a “no show” at two successive Lott House interviews that were set up by her supporters.

Her friends became alarmed that the guardian intended to keep Kasoundra in the New Rochelle nursing home for the rest of her life. Even the nurses told Kasoundra that she didn’t belong there.

Shocked by the guardian’s disregard for the judge’s orders, and worried about Kasoundra’s bleak future, one of her friends went to State Supreme Court and filed an “Order to Show Cause,” asking for the removal of the guardian and the full reinstatement of Kasoundra’s autonomy. Friends wrote letters of support, and the psychiatrist provided a notarized letter detailing the results of the mental status test and his conclusion that Kasoundra had no symptoms of dementia and could successfully live at home.

By taking the guardian to court, Kasoundra’s friend hoped to get answers to the following questions: (1) How had Samet been selected as the guardian? He appeared to have deep ties to Lenox Hill Hospital, which seemed like a conflict of interest since the hospital had brought the guardianship case against Kasoundra; (2) How had the guardian spent Kasoundra’s income? Due to her overly long hospital confinement, Kasoundra’s Social Security income had built up to $20,000 when the guardian took over, and $1,000 kept coming in every month for the two years he remained guardian; (3) Why hadn’t Samet followed the judge’s orders to return Kasoundra to her apartment or place her in Lott House? (4) Had the guardian been negotiating with the landlord to receive money for surrendering Kasoundra’s apartment, and if so, why hadn’t he disclosed this to Kasoundra? (5) Why had Samet purchased a $6,500 burial plot for Kasoundra when she had always wanted to be cremated? Where was the burial plot deed and/or the receipt for the purchase? (6) And perhaps most important, did her guardian intend to keep Kasoundra confined in the nursing home forever?

Judge Visitacion-Lewis did not reopen the case, but it was transferred to Judge Kennedy of Landlord Tenant Court who was presiding over Kasoundra’s eviction hearings. Her pro bono lawyer was still ardently struggling to keep Kasoundra’s apartment from being lost. A lawyer from Mental Hygiene Legal Services (MHLS) was assigned by the court to represent Kasoundra in the guardianship matter. But when the friend’s Order to Show Cause came before her, Judge Kennedy threw it out, saying that it was not written in the proper legal language. Because the order wasn’t heard, the friend’s candid questions for the guardian were never asked or answered under oath, and Samet ultimately provided the court with only a very vague account of his disbursement of Kasoundra’s income.

Judge Kennedy invited the MHLS lawyer to bring the same suit before her couched in the appropriate legal language. But when the new suit was filed, the MHLS lawyer did not ask for the reinstatement of Kasoundra’s autonomy; she asked only that the guardian be replaced.

Then began a lengthy series of hearings that dragged on interminably and never seemed to go anywhere. Sometimes the hearings were about the guardian, and sometimes they were about the landlord’s eviction proceeding. Nothing ever seemed to get resolved. Judge Kennedy would tell the guardian to do certain things, and he would come to the next hearing two months later without having done them.

A psychiatrist was appointed by the court to evaluate Kasoundra, but the hospital would not provide her medical records until they were subpoenaed, so his report was endlessly delayed. When the court-appointed psychiatrist finally testified, his assessment of Kasoundra’s cognitive status and her ability to live at home was virtually the same as the opinion provided three years earlier by the other psychiatrist.

Meanwhile, Kasoundra, who could walk perfectly well when she was in the hospital psych ward, was now confined to a wheelchair that set off an alarm whenever she tried to enter the elevator. No aide ever seemed to be available to escort her to the second-floor rooftop, which provided the only access to fresh air in the nursing home. Whenever she tried to walk, Kasoundra was told to get back in her wheelchair, and she spent her days wheeling herself up and down the hall.

The staff members were apologetic but said they had to follow the written orders of the guardian. After considerable pressure was applied by Kasoundra’s friends, she finally received a brief, five-week stint of physical therapy. But when the therapist recommended that Kasoundra be transferred to the “walker program,” the guardian wouldn’t authorize it.

Meanwhile, the guardian never visited Kasoundra in the nursing home except once, when her friends finally persuaded him to do so. Kasoundra begged him not to give up her apartment or dispose of her artwork and possessions. She pleaded with him to let her go back home.

As the case dragged on, Kasoundra’s supporters began to reach out to foundations to help pay Kasoundra’s back rent when and if her case was ever decided. The HOWL! Emergency Life Project suggested that Kasoundra might like to live in the lovely Lillian Booth assisted-living home in New Jersey. Kasoundra’s MHLS lawyer obtained a pass for her to leave the nursing home to visit the Lillian Booth, which was surrounded by acres of verdant grounds and had a resident cat. Its occupants were elderly actors and jazz musicians, and the ambiance was lively and attractive. The staff welcomed Kasoundra and placed her on the waiting list.

When Judge Kennedy learned of the Lillian Booth initiative, she heartily approved, and she quickly replaced Kasoundra’s guardian with Integral Guardianship Services of Coney Island. She gave permission for the new agency to dispose of Kasoundra’s apartment, and instructed them to pursue Kasoundra’s application to the Lillian Booth. She then terminated the hearings, leaving Kasoundra with no judicial oversight.

This proved to be tragically premature, because the new guardian, Alan Shapiro, immediately disposed of Kasoundra’s apartment but made little effort to acquire the documents needed for Kasoundra to be admitted to the Lillian Booth home. He said that it was just “too much trouble” and that there was “too much paperwork” involved. And although Judge Kennedy had ruled that an inventory be made of Kasoundra’s artwork, and its value professionally assessed, no such inventory was made before Shapiro moved it to a storage facility in Brooklyn.

The MHLS lawyer told Kasoundra’s friends that she had seen many cases where guardians stopped paying the storage fees, and their clients’ possessions were then permanently lost.

A final eviction hearing took place in Judge Masley’s courtroom, where it was determined that Kasoundra and a friend could visit the storage facility and make an inventory of her artwork and effects. But in spite of repeated requests, Kasoundra has not been allowed access to her possessions.

More than six months have passed since Kasoundra’s case was closed, and she is still in the nursing home in New Rochelle, far from her community and friends. It is rare for visitors to make the time-consuming and expensive train trip to New Rochelle to see her, and Kasoundra often feels despondent.

Four long years have elapsed since the fateful night she was taken to Lenox Hill Hospital and subsequently lost her right of self-determination. She worries about her artwork and how long it will be preserved by the guardian. She wonders if her furniture and memorabilia were put in storage or thrown away.

She is fearful when she contemplates the very real possibility that she could remain trapped in the nursing home against her will until she dies.