The World Chess Championship taking place in South Street Seaport has sweeping views of the East River, a swanky VIP viewing area and bar, and the sport’s premier star and sex symbol — Magnus Carlsen — being ably matched by Sergey Karjakin, a Putin-supporting challenger.

“It’s not nearly as good as ’95,” says attendee Dan Schaeffer.

Everyone’s a critic.

That was the last time the championship was held in New York City, then on the 107th floor of the World Trade Center. Schaeffer, 63, a self-described “serious amateur” from New Jersey, liked the low-tech entertainment: American grandmasters acting out the game for attendees in the flesh.

Since then, chess’s governing body has introduced technological upgrades to provide a sleek, modern and exciting viewing experience — move-by-move commentary coupled with big screens showing the board and possible next moves. For viewers with virtual reality devices, “stereoscopic live video” was available.

Still, whether you go modern or retro, it’s not exactly easy to jazz up the viewing experience of this best-of 12 contest between two of the world’s top chess players, which runs for the rest of the month here in Manhattan. It is what it is, and you either find it exciting or you don’t. And that drama is contained within a few dozen square fishbowl feet.

Schaefer nods in the opposite direction of the river views and screens. “Have you been to the room?”

Competitive chess is its own world

It should be noted that the room is not really important for the serious chess players — those who speak in the rapid fire language of “Bishop F3” and “Pawn C4” and “Queenside attack.”

In that community, it’s plenty easy to get excited about the unfolding match just by looking at the screens tracking the slow motion of pieces white and black — and some moves take many long minutes of motionlessness.

“Usually in these things someone breaks,” says Bruce Brinker, 40. He came from Pittsburgh to watch a few rounds and wanted to arrive towards the beginning in case Karjakin “cracks early.”

That’s not out of the question in high-pressure matches like this, for which Brinker struggled to find an appropriate analogy. The players pore over the table “like surgeons,” he said.

They have the endurance of “marathon runners,” in a sport where the margin of error is so small and players have to remain constantly vigilant. They’re “walking a tightrope,” he says. “It’s hard to…” he trails off.

Both players are prodigies, he explains. At age 13, Carlsen drew in rapid chess with the then-#1 ranked player in the world; Karjakin became the sport’s youngest ever grandmaster at age 12 and seven months.

In this meeting Carlsen is the overwhelming favorite — which explains why he’s one of shall we say zero other chess players who have modeled with Lily Cole.

Yet Karjakin has held his own so far, now four games into the championship, including a fourth draw on Tuesday — his defensive but slippery style is almost discernible even to a rank amateur like this writer. You can see by the way his pieces remain clustered, as if huddling, while his opponent probes long attack lines and control of the center. Still, Karjakin has pulled off Houdini-like escapes.

Apparently this and more is all perfectly seeable on the screens, and the iPhone apps at which people are peeking. Brinker acknowledges that he could probably just as easily watch at home. He doesn’t really need the room.

In the room where it happens

Which might explain why a true chess-know-nothing can get inside.

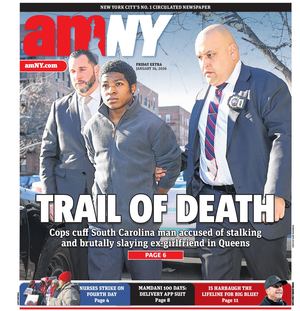

Winding through the mainly male crowd of approximately 200; leaving behind the vague smell of international cologne that permeates the hall; at the center of the building you come upon a set of double black curtains, staffed by smartly dressed security guards — who check that your cell phone is on vibrate and its camera’s flash is off before you are allowed into the room.

It is small and nearly dark, largely empty, cushioned by carpeting and strangely purple light, fronted by a double glass wall, a few feet beyond which sit the players and the board.

At moments of the hours-long match, you can get up close and watch: Carlsen looks at ease, his right leg crossed lazily over his left, a little skin showing between socks and pants. He makes moves decisively, then scratches notations on paper to his left.

Karjakin hangs his suit jacket carefully on the back of the kitschy office chair, rarely moving other than shifting the position of his fingers from his forehead to the back of his head. He stares intently down.

The only sound is the air-conditioning. It’s hard to even see the board, and to the extent that you can, it looks fake. From time to time, the players get up and leave the board behind, because in reality that’s just a placeholder, too — the real game is in their heads and out of view.