This is part of our series NYCurious, where we answer your questions about the city. Tweet or Facebook Message your queries to us at @amNewYork, with #NYCurious.

Staten Island is the only New York City borough not connected to the subway. Isolated by water on all sides, residents of what’s often dubbed the “forgotten borough” have to depend on a 25-minute Staten Island Ferry ride before their feet even touch a subway platform.

But, did you know Staten Island had a plan for a subway that was never built?

Construction was started; officials were excited for it; but everything came to a halt, leaving many with suspicions that have lingered for decades.

What actually happened to the project? Scroll down to learn more.

What was the proposal?

The Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT), now known as the New York City Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the MTA, was the private operator of the original subway lines in 1904. They joined other transit systems in the New York City boroughs to create services that connect Queens, the Bronx, Manhattan and Brooklyn.

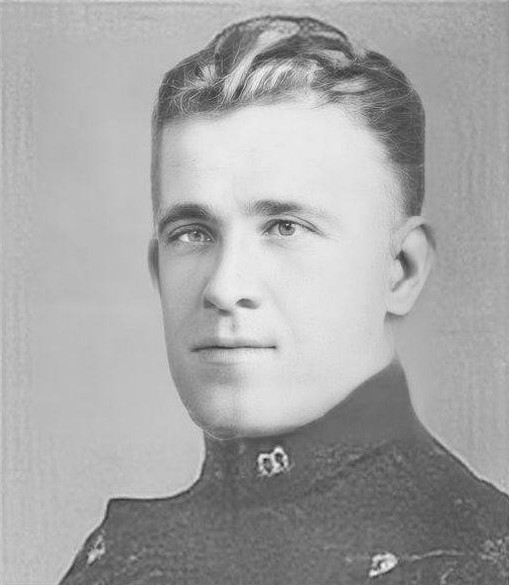

That, of course, left out Staten Island. At the time, Staten Island Borough President George Cromwell insisted the borough deserved a physical connection to the rest of the city, according to archives from the Staten Island Museum. In 1912, a Cromwell plan was approved that called for a tunnel between Tompkinsville and 67th Street in Brooklyn, but that was shelved when Cromwell was defeated at the polls in 1913.

By 1918, Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT) revived the proposal with the idea of a subway tunnel that would connect the borough to the IRT system.

“This was a period of time when New York City was becoming the city we see it as today,” said Jonathan Peters, a professor of finance and data analytics at the College of Staten Island and transportation researcher for the Staten Island Museum’s archives. “Staten Island became a part of New York City for this exact reason — for transit connections, with easy access into the city.”

Plans were put in motion by the 1920s, when officials decided to connect Staten Island’s pre-existing railway (then known as Staten Island Rapid Transit and owned by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad) in St. George to the rest of the subway system at the 59th Street station in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, which is now served by N and R trains. The trip was projected to take between eight and 10 minutes, according to an old newsletter from the Westerleigh Improvement Society.

By this time, slogans such as “Ten minutes to Broadway,” “A subway for Richmond,” and “To and thru without transfer,” were posted around Staten Island, envisioning a brighter future.

“The tunnel at the 59th Street station was awaiting the arrival of a train from Staten Island,” said Peters. “And Staten Islanders were waiting for it, too. The subway would have not only helped the borough’s population growth, which was barely 200,000 at the time, but it would have changed the communities along the stops.”

Before construction could begin, however, the BRT went bankrupt.

Tunnels to nowhere

In 1921, then-Mayor John F. Hylan and the city’s representatives in Albany introduced a bill requiring New York City to construct a freight and passenger tunnel under the Narrows, the tunnel straight between Staten Island and Brooklyn, Home Reporter and Sunset News reported in 1964.

Though the tunnel would no longer serve as an extension of the subway system, it was to operate as a separate railroad. A connection was to be built for the passenger tube at the Fourth Avenue subway, while the freight connection was to be with the Long Island Rail Road near Sixth Avenue, Brooklyn, said Peters and articles from the SI Museum archives.

Excavations began on April 14, 1923, at Shore Road in Bay Ridge. Three months later, construction on the Staten Island side near Victory Boulevard in Tompkinsville started.

The project consisted of building two 24-foot tunnel tubes on either side, totaling four altogether. The Brooklyn-Richmond Freight and Passenger Tunnel was expected to be the longest underwater tunnel by its completion in 1929, reported the Staten Island Advance.

Staten Island residents were given hope whenever they saw the sign at the construction site that read, “On this site will be sunk the Staten Island shaft of the freight and passenger tunnel . . . across the Narrows,” according to SI Museum archives.

The plan gave the Staten Island Rapid Transit an opportunity to transition its trains from steam-powered locomotives to Brooklyn-style electric cars, the Home Reporter and Sunset News reported. However, by the time the luxury upgrade was finished in 1925, the tunnel idea had been put back on the shelf.

“Staten Island electrified their trains because they wanted to match what the Brooklyn subway cars looked like,” said Peters. “Staten Island was gearing up to be a part of the subway system. But now with plans out the door, having the trains electrified gave the borough hope that someday they would get the subway system connected.”

The construction itself only lasted a year. Shafts from ground level down to the tunnel had already been built on both east- and westbound sides, extending 150 feet into the harbor.

Bids for further construction were advertised in 1925, but no contractors jumped on it. The idea of a railroad or freight line lingered for a while, before being completely “forgotten” like its borough’s nickname, by the 1930s.

According to several archive news clippings, the city spent $6 million, yet the only thing left to show for it is Brooklyn’s side of the tunnel, which still exists under Owl’s Head Park in Bay Ridge.

Why was construction halted?

John Delaney, chairman of the Board of Transportation, gave Staten Island the news when he stated the tunnel connection would not be a priority.

“I think I can say with authority that the city will first take care of new subways,” the New York Herald Tribune reported Delaney said in 1924. “I’m convinced that they are more important than the tunnel to Staten Island. We need new lines in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens. These are our first objectives.”

However, many theories have surfaced over the years as to what really happened to the tunnel project.

One theory is that then-Mayor Hylan, who had previously been fired by the BRT, tried to get back at the transit system by putting them in bankruptcy. Had the company not gone bankrupt, the project could have continued and eventually been completed, many believe.

Hylan, however, said in the Sunset News article the tunnel would have been “one of the greatest public improvements the great City of New York has ever undertaken.”

Another theory revolves around former Gov. Alfred Smith, who at the time had stock in the Pennsylvania Railroad, which was a big competitor to Baltimore & Ohio. Word spread that Smith potentially feared the construction of the freight tunnel would destroy his monopoly on cross-Hudson cargo transport, The New York Times reported.

Smith reportedly said the tunnel to Staten Island would be “hope and a hole in the ground.”

Peters admits the Brooklyn-Richmond freight and passenger rail was not a priority at the time, but insists it’s more than just a story of bad planning.

“The focus has often always been on Manhattan; look at its economic success. There’s a strong bias against Staten Island versus other parts of the city,” said Peters. “Whether it was funding or politics, no one will ever admit whatever the behind the scenes reasons was. And yet even years later, we sit here with questions and a tunnel that was never finished.”

Modern proposals

The idea of Staten Island having a subway connection is still talked about.

Many residents wonder if a subway on the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge would have been a feasible fix, but we can’t reconstruct history.

“It’s an unfortunate missed opportunity that we cannot fix today,” said Peters. “[Builder] Robert Moses could have included it into his plans when constructing the bridge, but the vision was the subway idea would diminish, and automobiles were the future.”

Today the Staten Island Ferry sees more than 70,000 passengers daily who commute via mass transportation rather than drive on congested highways.

Peters said to have a subway in Staten Island in 2018 would be “greatly needed, but realistically? It will never happen.”

In 2010, legislation was introduced in the City Council that called on the city Department of Transportation and the MTA to “institute a plan for the construction of a Trans-Narrows Tunnel between the boroughs of Brooklyn and Staten Island for the purposes of connecting the Staten Island railway to the New York City subway system.”

Nothing further came about until six years later when Borough President James Oddo received a letter from MTA head Tom Prendergast, in which he described exactly why a subway tunnel would never make its way to the borough.

Prendergast wrote that a rail connecting Staten Island to Brooklyn would be challenging, stating that funding constraints were a major consideration in the decision to not undertake a complex and politically charged project, the Staten Island Advance reported.

One of Prendergast’s main concerns was that, if it were to happen, operating additional service along the Fourth Avenue N and R lines in Brooklyn would be “extremely challenging on the Staten Island side.”

In 2010, state Sen. Diane Savino tried reigniting the proposal, the Staten Island Advance reported, but stated it would set the city back by $3 billion.

However, if the New York City Transit Authority ever received funding to make the tunnel a reality, Prendergast wrote, “the hypothetical ‘next steps’ would be to start with some sort of high level needs/feasibility study to understand what the potential benefits for this would be, what sort of land use changes it would induce, what development would be required and what sort of routing and service options would be feasible.”

For now residents will have to continue to rely on the ferry.