There are portraits that flatter. There are portraits that romanticize. On rare occasion, however, there are portraits that reveal so much of the world that birthed them, one forgets the sitter entirely and falls headfirst into the unrelenting tangle of time.

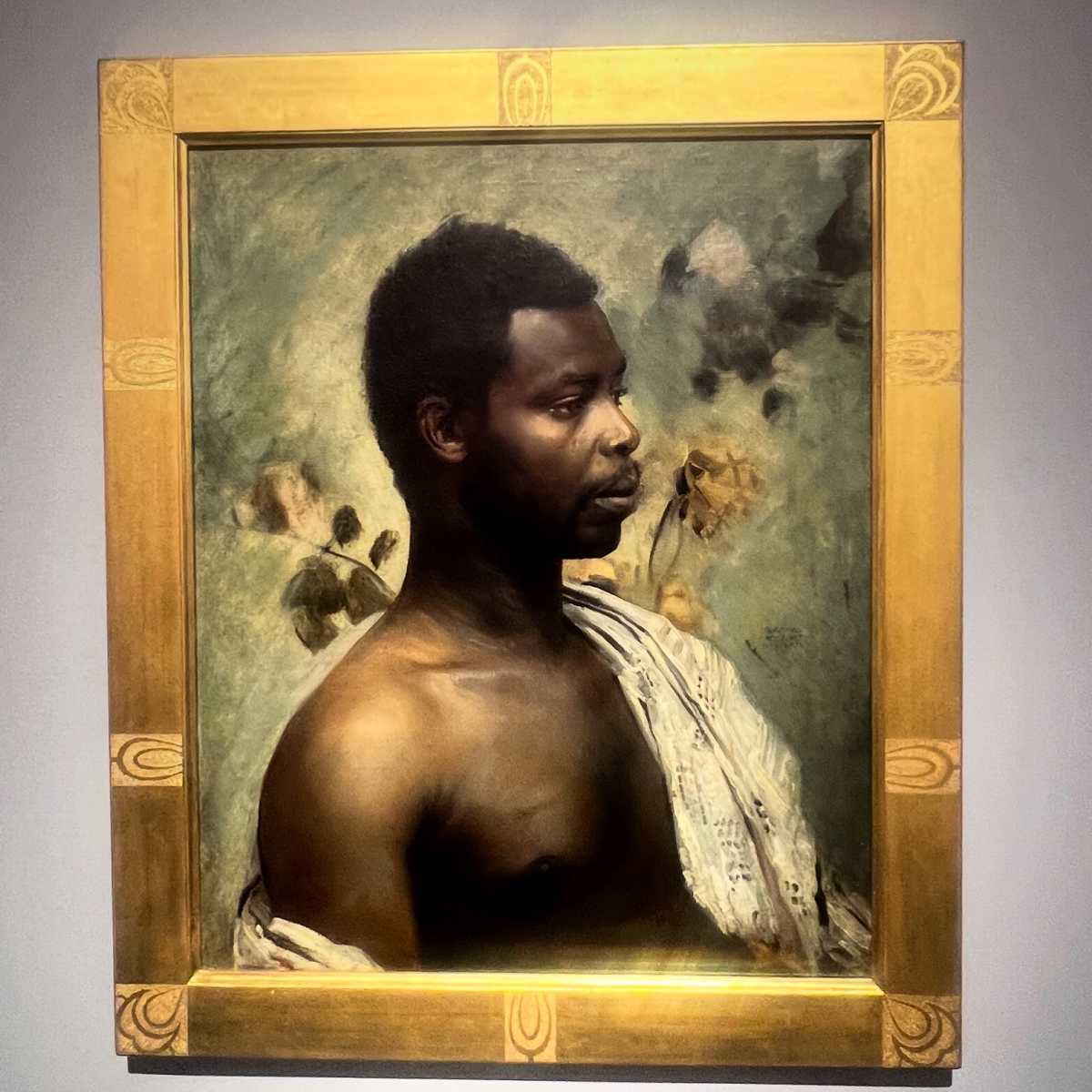

Such is the case with Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona (1897)—a quiet storm of a painting, no larger than a café windowpane, yet seismic in its cultural implications. Displayed this April at TEFAF Maastricht, amidst the glittering reliquaries of Old Masters and newly minted blue chips, the work did not simply hang. It seethed. It stood. It declared itself a barometer of the age and demanded its reading.

Painted by Gustav Klimt, in tandem with his academic co-conspirator Franz Matsch, the work appears on the surface to be a regal portrait of a young African prince. History, like art, rarely offers the courtesy of a surface reading.

In truth, the boy was no prince—at least not in the way the Austrian public had been told. Dowuona, like others from his Osu community in present-day Ghana, was brought to Vienna as part of a grotesque ethnographic exhibition staged at the Tiergarten am Schüttel. Human beings—men, women, and children—were paraded as living specimens for the voracious gaze of the imperial elite. Misidentified as Ashanti royalty to heighten the European fantasy of noble otherness, Dowuona’s image was filtered through a colonial lens so thick, it would take more than a century to see him clearly.

He still stares back.

His portrait, completed in the same breathless decade that would birth The Kiss, serves not as a decorative indulgence but as an indictment, an artifact, and a mirror. It is one of Klimt’s earliest entanglements with the human condition not as allegory or erotica, but as ethnographic theater. As art.

This is where the conversation must turn—not to Klimt alone—but to the role of art itself.

Art as the great measurement of our souls

To collect art is to collect temperature. It is to cup one’s hands around the pulse of a moment—its tremors, its contradictions, its redemptions—and call it into permanence. Art is the only archive we possess that listens as deeply as it speaks. It does not forget. It does not soften. It tells the truth as we are too frightened, too polished, or too polite to say.

When speaking of hindsight, one must look to history’s artworks as forensic evidence of civilization’s recurring appetite for power, its flirtations with control, and its romantic betrayals. Art is not only the residue of what was. It is also the scaffolding of what is to come.

This is the reason Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona matters—not merely in its exquisiteness or provenance, but in its refusal to vanish into the annals of Klimt’s lesser-knowns. Its resurgence today—amid new debates about restitution, racial narrative, and curatorial ethics—serves as a form of quiet insistence. The canvas is not just a surface. It is a stage. Sometimes, it is a battlefield.

A market reckoning

This portrait’s reappearance at TEFAF—not within a museum, not under the moral weight of institutional exhibition, but inside the transactional theater of the international art market—offers its own parable. The market itself has always been a form of performance.

Collectors circle. Catalogues gleam. Pedigree dances with price point. Amidst the choreography, one must pause and ask: is this beauty being purchased, or is this absolution?

To acquire this work is not to merely own a Klimt. It is to inherit a question. It is to cradle the ghost of imperialism’s artful lies and to decide—boldly and publicly—what role beauty should play in our understanding of violence.

For those who acquire such works today—whether historical or contemporary—this is a call to courage. Art is not décor. Art is declaration. Whether placing a Slonem into a penthouse foyer or a Swallah into a boardroom, collectors must come to understand that they are not decorating space. They are mapping legacy.

A portrait reclaimed

Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona must not be resigned to the private chambers of the elite, whispered about only in auction catalogues and exclusive dinner circuits. It must travel. It must teach. It must be placed within the Museum of African Diaspora. It deserves to be discussed beside Kerry James Marshall and Kara Walker. It must be seen—fully, contextually, painfully, and triumphantly.

Dowuona was not meant to be remembered. He was meant to be consumed, mislabeled, and filed away. Yet here he is, dignified in brushstroke, luminous in presence, and finally—finally—called by name.

To honor this work is not to forgive its origin. It is to understand its function. Art, at its most piercing, serves both hindsight and forethought. It is a document of what we were, and a blueprint for what we must become.

Look closer. Do not look away. This is what art was made for.