Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was a contradiction incarnate—an aristocrat of decay, a chronicler of ecstasy, and a genius whose frailty sharpened his perception of life’s most urgent truths.

To encounter his work is to confront not the prettified myth of the Belle Époque, but the pulse beneath its velvet glove—the Paris of smoke, sweat, and laughter echoing through Montmartre’s cabarets. His life and legacy form a thesis on the radical power of observation, the elevation of the marginalized, and the alchemy of transforming human imperfection into immortal art.

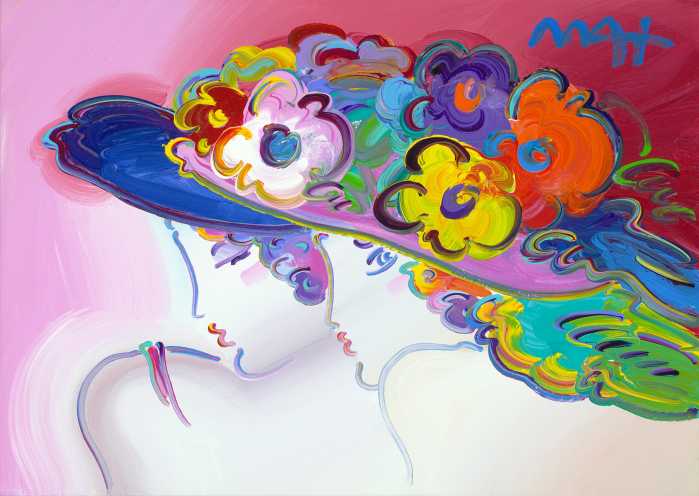

Selected works by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec are currently on view at Park West Gallery, Soho—an opportunity to experience the genius of an artist whose line forever blurred the boundary between the sensual and the sacred, the fleeting and the eternal.

The Anatomy of the outsider

Born in 1864 at the Château du Bosc, Toulouse-Lautrec was a child of French nobility, yet his lineage carried both privilege and its curse.

The inbreeding that sustained his aristocratic bloodline left him physically stunted after two leg fractures in adolescence, his frame permanently shortened and fragile. Yet what nature withheld in stature, it compensated in vision. His physical confinement gave rise to a mental liberation—an eye so acutely tuned to nuance that every gesture, every tremor of emotion, became revelation.

He was drawn not to the salons of the upper class, but to the demi-monde—to those who lived without illusions of immortality. In the brothels, cabarets, and dance halls of Montmartre, Lautrec found his true fraternity: dancers, drunks, dreamers, and courtesans who lived life as both art and resistance. Where others saw sin, he saw humanity unmasked.

The Paris of flesh and spirit

The 1890s in Paris were an age of contradictions—religious guilt beside erotic excess, industrial progress beside existential despair. Lautrec’s genius lay in rendering this moral chiaroscuro without judgment. His subjects—the dancers of the Moulin Rouge, the singers of Le Mirliton, the weary women of Rue des Moulins—were captured not as curiosities but as companions. His line was merciless yet merciful, sketching not only form but the fleeting dignity of being seen.

He shared creative kinship with Degas and Van Gogh, and a deeper, unspoken connection with Modigliani: both men ravaged by drink, both outsiders by nature, both obsessed with preserving what society preferred to discard. Together, they redefined the parameters of beauty and moral worth, shifting art’s focus from idealization to empathy.

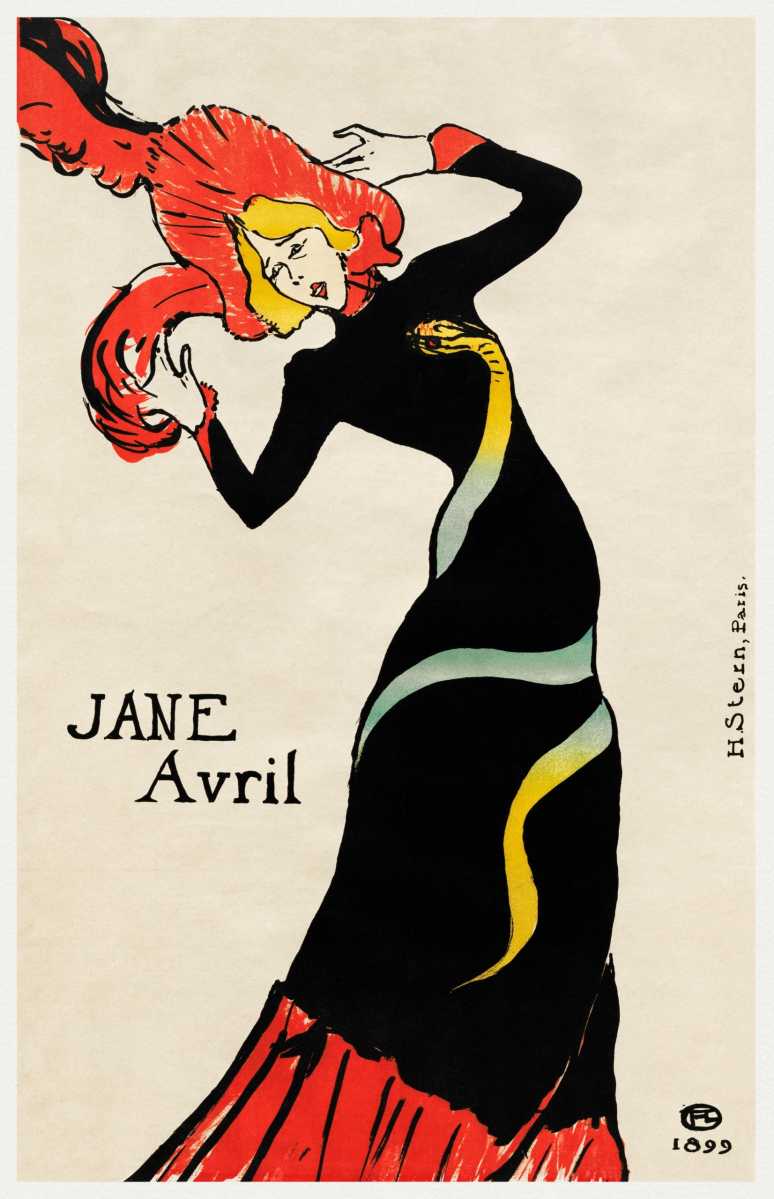

The revolution in print

Toulouse-Lautrec’s most enduring contribution to art may be his transformation of lithography from a commercial tool into a fine art medium. His posters—those vibrant, pulsating declarations plastered across Parisian walls—were more than advertisements; they were cultural manifestos. With them, he democratized art, dissolving the barrier between the elite collector and the passerby.

The Moulin Rouge: La Goulue lithograph remains one of the most iconic images in Western art, not merely for its aesthetic brilliance but for what it symbolized: the arrival of the street as gallery, and the artist as anthropologist of the modern condition. His mastery of line, economy of color, and psychological precision still inform visual culture today—from Warhol’s Pop silkscreens to contemporary design.

The power of the graphic medium

In today’s collecting climate, the graphic medium has emerged once again as both an entry point and an apex of discernment. The lithograph, the etching, and the fine art print offer what the modern collector craves most: tangible history and profound value, unburdened by the excess of speculation. Acquiring a Lautrec lithograph is an act of refinement—an alignment with the legacy of innovation and intellect that defined the birth of modern art.

For those within the luxury market, the acquisition of works on paper offers an extraordinary balance—exceptional cultural and historical weight without compromising fiscal prudence. These pieces, often crafted in limited runs, possess the intimacy of the artist’s hand and the immediacy of his thought. They carry prestige, permanence, and accessibility in equal measure—a union rarely found in the contemporary art economy.

To collect a Lautrec lithograph today is to embrace both aesthetic and strategic intelligence: it is to hold a fragment of history that remains vital, vibrant, and increasingly sought after by a new generation of sophisticated collectors.

The redemption of the gutter

In an era obsessed with propriety, Lautrec’s art was heresy. He rendered the so-called “fallen” with the same reverence others reserved for saints. He believed that truth—no matter how raw—was the only path to transcendence. Each pastel stroke and lithographic curve was a kind of redemption, a reclaiming of the humanity denied to his subjects by polite society.

His brothel scenes, far from salacious, are studies in empathy: the languid sprawl of fatigue, the absent gaze of routine, the quiet communion between women who lived outside of grace. In these intimate interiors, the artist’s tenderness eclipses voyeurism. He neither moralizes nor romanticizes—he dignifies.

Legacy and continuum

Today, the resonance of Toulouse-Lautrec’s work endures not only in museums like the Tate, the Musée d’Orsay, and the National Gallery, but also in the rare collections that still allow the public to stand before his prints and feel their vitality. Among these is the Park West Gallery in Soho, where collectors and admirers can witness his genius up close—a rare opportunity to engage directly with the lineage of modern art’s genesis.

To view a Lautrec in person is to stand at the origin point of visual modernity—to see the intersection where decadence meets devotion, and pleasure becomes philosophy. Each work hums with the energy of the streets that birthed it: audacious, intimate, alive.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec lived as he painted—with ruthless honesty and unrestrained compassion. He gave form to the formless, dignity to the debased, and voice to those the world refused to hear. His art invites us to reconsider what beauty is, and who decides.

Collecting Lautrec is not an act of acquisition—it is a gesture of alignment with an artist who saw humanity in its truest light: fractured, imperfect, yet incandescently real.

Visit Park West Gallery at 411 West Broadway and reach out to kjasven@parkwestgallery.com.