Wearing buttons with a heart and the text “save this landmark,” a crowd on Thursday packed an Upper West Side community board committee meeting seeking to prevent the sale and demolition of the West Park Presbyterian Church.

The church sought to win support from Community Board 7’s Preservation Committee to demolish the landmarked West Park Presbyterian Church, at 165 West 86th Street and Amsterdam Ave.

The more-than-a-century-old building was built in 1890, designated a landmark in 2010, and has housed numerous arts groups from dance to theater to music – as well as being used by another church for services.

The Center at West Park, a theater and arts organization evicted from the church on July 7, is doing a temporary residency at the St. Paul and St. Andrew United Methodist Church, a few blocks away.

To demolish the more-than-a-century-old structure, the church must show the New York City Landmarks Commission, which rarely approves such demolitions, that it meets “hardship” requirements.

“The bottom line is that this application doesn’t meet the city’s statutory test for hardship,” said Andrew Goldwyn, director of public policy for the New York Landmarks Conservancy. “The building can still be used for the purpose for which it was built. Another congregation worships there now.”

Representatives of the church said the structure was too costly to repair and the application should be granted.

“It’s true that the hardship application is a rare process, but it is a really imperative part and an essential component of the landmarks law,” said Valerie Campbell, a partner at Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer, representing the church. “We believe that if you examine our application, and there are hundreds of pages, that it’s abundantly clear that the church has met these standards.”

The church has reached a deal to sell the building to Alchemy Properties, which would develop the site to include 10,000 square feet that could be used for worship, community and culture.

In what looked like a tale of two churches, church representatives described a ramshackle building in need of tens of millions of dollars to repair, while renovation advocates, near a mockup of a $3 million check they received from the state for that purpose, said other studies showed it would cost one-tenth of that.

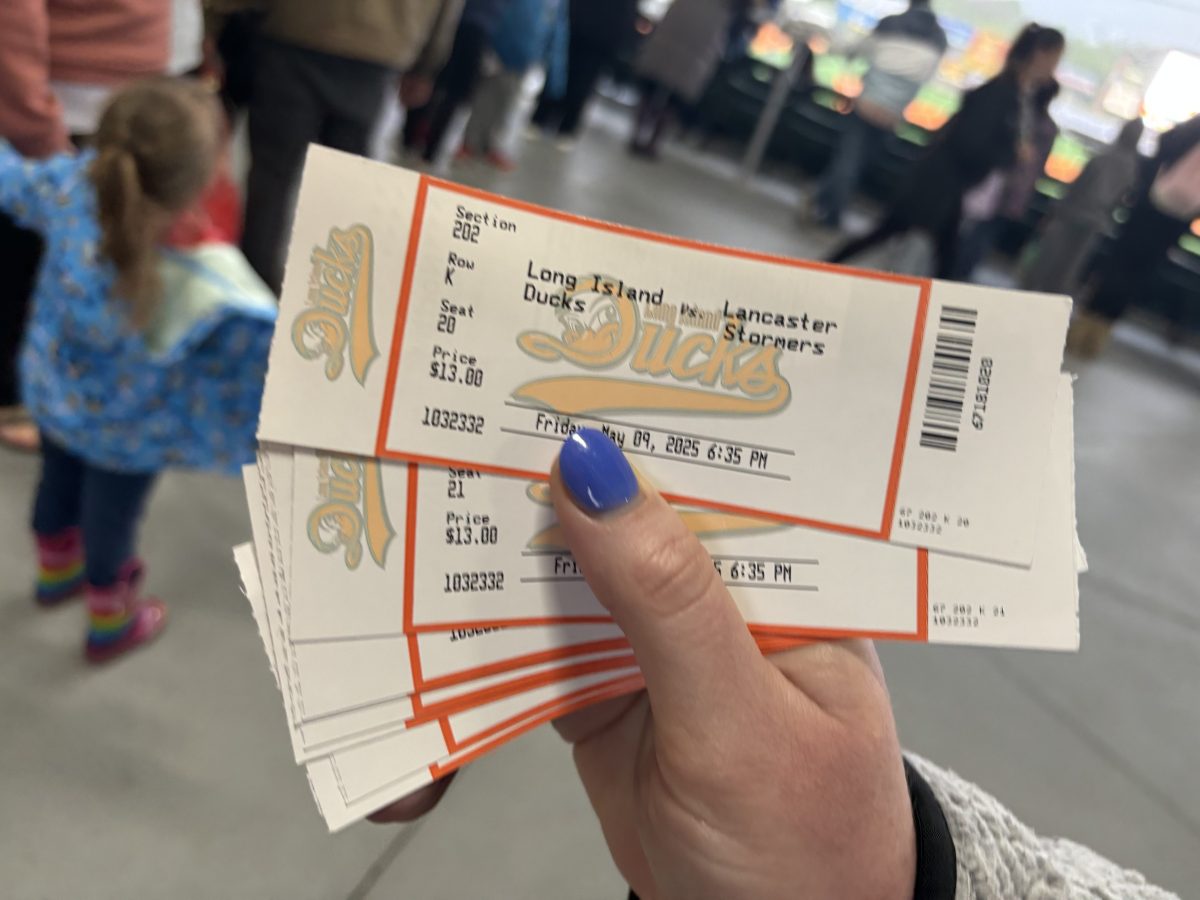

They said they have millions more to help and brandished three envelopes each with $30,000 for rent at the meeting, which would lead to an opinion that is only advisory, but could prove pivotal.

“That damn building is not falling down and don’t let anybody tell you it is,” said City Council Member Gale Brewer, who helped obtain landmark status. “This is a building that’s a landmark. It is beautiful for the architectural reasons that many of you know. When you landmark a building, it’s done for a reason. It should continue to be standing and be a landmark.”

Legislators lined up at the meeting and online to save a landmark that they said was lively and could be renovated, rather than removed.

“This, while in need of repairs, is reparable,” State Senator Brady Hoylman-Sigal said via online testimony. “The landmarks law was enacted to prevent outcomes like this.”

A spokesperson for Congressmember Jerrold Nadler said this was about loss of a landmark and a structure and services vital to the community.

“It would be a real loss for the Upper West Side if this building were to be demolished,” the spokeswoman said. “There are viable avenues to pursue that would help steer the preservation of this church and bring it back to its glory.”

While church representatives, and some in the audience, described the structure beneath a sidewalk shed as in desperate need of repairs, others saw this as the poster child for demolition by neglect.

“This is extremely valuable,” New York City Public Advocate Jumaane Wiliams said online. “Now more than ever, we need spaces where people can commune, where creative and artistic types can really get together and feed off each other.”

The West Park Administrative Commission, which oversees the church, initially filed a hardship application with the Commission in April 2022, but withdrew it in January 2024 and is resuming the process.

Church representatives said all Presbyterian churches are owned by their congregations who are solely responsible for their upkeep.

The building’s costs nearly drove the congregation bankrupt, they said, while accumulating debt and leading to the sale of assets and inability to compensate clergy.

“The building, particularly its façade, began to develop maintenance issues,” said Roger Leaf, chair of the West Park Administrative Commission. “As these took over, membership began to decline.”

He said a sale would create a multi-million-dollar Social Justice Fund and “build the congregation a new, state-of-the-art space for worship and community activities for the Upper West Side.”

Leaf said the Alchemy deal would provide up to $30 million to the Presbytery of New York City and directly impact underserved communities across the five boroughs.”

“This fund will provide desperately needed resources for community services at a time when such programs are under attack,” he said.

A sidewalk bridge was erected in 2000 to protect pedestrians from falling pieces of the facade, which would come down either through demolition or repair. Church representatives called it a sign of severity, while advocates see it as proof of inaction and neglect.

“I think if you look at the record, you will see that the church was not in good condition,” Campbell said of its status when landmarked. “It was actually closed. They had a plan. They were going to try and restore the main sanctuary.”

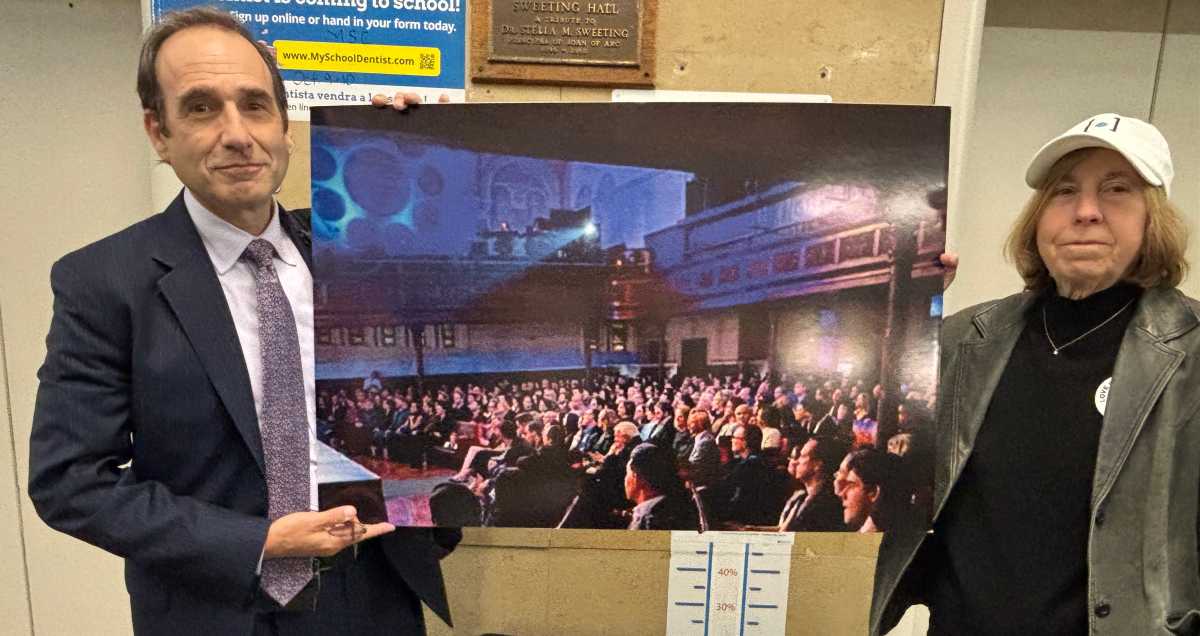

West Park Center Executive Director Debby Hirshman, who helped raise $65 million to build a new, 11-story, 137,000-square-foot Jewish Community Center on the Upper West Side, said they have millions that could be used for repairs.

“Sign documents that allow the sidewalk shed to come down,” she said. “We have the money to do that.”

To qualify for a hardship exception, the church must show the property can’t earn a “reasonable return” and isn’t “adequate, suitable, or appropriate for use by the owner for the purposes to which it is devoted.”

Advocates argued another church already meets there and thousands have attended hundreds of performances, showing a photograph with a crowd packed in for a performance at a location they said is in need of TLC more than RIP.

“Turning the hardship down would not guarantee that the building would be preserved,” Leaf said. “The building would continue to decline until a buyer could be found. The sidewalk bridge surrounding the building would likely remain in place for the foreseeable future.”

A second meeting is scheduled for October 29 to hear additional testimony over what has turned into a heated debate over this structure.

There have been only 19 such hardship applications since 2009, with almost all denied, although an application to demolish St. Vincent’s was approved by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2008.

That allowed the hospital to demolish the O’Toole Building in the Greenwich Village Historic District to make way for a new medical center.