BY EILEEN STUKANE | Despite the current mood of détente between the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and local elected officials over plans for replacing the time-worn West Side bus terminal, it’s not yet clear just how committed the Port Authority is to heeding the community input it says it welcomes.

For now, there is a promise to hold future public meetings, and there will be plenty to discuss about five new alternatives unveiled late last month by the Port Authority. At Community Board 4, opposition to any new bus terminal on Manhattan’s West Side remains strong.

Of the five designs, each from a different architectural firm and ranging from $3.7 billion to $15.3 billion in cost, at least one, featuring a rooftop park, would require demolishing neighborhood buildings through the use of eminent domain, a legal procedure that allows government to require a private property owner to sell land needed for a public use.

Eminent domain was already a hot issue in public discussions about a new Port Authority bus facility. The initial concepts the agency put forward last year strongly relied on eminent domain, which “would tear out the heart of the Hell’s Kitchen area directly across the street,” Community Board 4 member Betty Mackintosh said at a recent Clinton/ Hell’s Kitchen Land Use Committee meeting.

Those plans, which she charged were “flawed and secretive,” would have demolished homes, small businesses, and other community institutions.

Mackintosh now heads CB4’s Hell’s Kitchen Working Group, which has been collecting a broad range of information about the Hell’s Kitchen South area — on measures from the number of residences to air quality — as part of its effort to “battle with the Port Authority,” as she put it at the meeting.

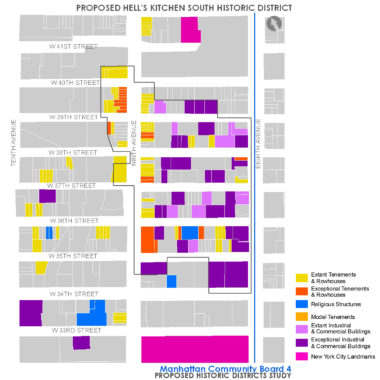

One potential weapon in CB4’s fight for the community could be the creation of a Hell’s Kitchen South Historic District, currently envisioned to encompass the area from Eighth Avenue to just west of Ninth Avenue between West 41st and West 34th Streets. A landmarked district cannot easily be altered, and the use of eminent domain cannot be employed.

The idea for the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) to designate this section of Hell’s Kitchen as an historic district actually first surfaced at CB4 in 2010.

“A body of research was done in 2010, but the work was tabled in deference to other more urgent matters at the time,” explained Dale Corvino, a CB4 member who, along with board public member Brian Weber, is spearheading the CB4 Landmarks Task Force. “The work was reactivated when we saw the continued loss of significant buildings and the plans of Port Authority.”

Metro Baptist Church at 410 West 40th Street would be within the proposed historic district, and according to its pastor, Reverend Scott Stearman, the Port Authority plans for a new bus terminal have intensified what has long been a community goal.

“The historic district has been in the minds of some neighborhood people for some time,” Stearman said. “I think this has added a bit of energy to the fire. I do see it as a tool in the toolkit. I’ve been appreciative of all the elected officials. If [Port Authority officials] are going to make this kind of transformative change, then it really needs to be thoroughly vetted and all stakeholders engaged.”

Corvino explained that the benefit of an historic district designation is that “the buildings that are within an historic district, and of historic significance, can’t be demolished. Being within an historic district saves them, and that’s the goal, to prevent further demolition.”

He noted that the Port Authority’s plans could make incursions into areas of Hell’s Kitchen South with early 20th century industrial buildings of 10 to 20 stories that have setbacks that bring light and air into the streets.

“Some of the buildings are more significant than others,” said Corvino, “but it’s not so much about an individual building that we want to save, it’s about an area of buildings of a certain character that we’d like to prevent from being lost forever.”

JD Noland, chair of CB4’s Clinton/ Hell’s Kitchen Land Use Committee, however, noted that CB4 is only in the early stages of its drive to create a new historic district.

“The process has just started,” Noland said. “We’ll discuss it, get some ideas, fill out the LPC form. Once we do that, we’ll talk about it in committee, take it to the full board, say, ‘Here are some of our ideas.’ It takes time to figure out.”

Meanwhile, as the Port Authority moves forward, some local residents wonder whether a new bus terminal should be situated in an increasingly densely packed West Side at all. On its website, CB4 reports that on a weekday the existing terminal serves approximately 220,000 passenger trips and more than 7,000 bus movements. Estimates are that by 2040, peak-hour passenger traffic will increase between 35 and 51 percent and bus traffic will jump 25 to 39 percent. Despite that, the Port Authority has adamantly opposed any discussion of locating a new bus terminal in New Jersey, which would require transfer to rail for a trip into Manhattan.

“They want to take over Hell’s Kitchen and make it part of New Jersey,” said Noland. “The New York side is pushing back and saying, ‘Wait a minute, you should have something in New Jersey and not destroy the neighborhood here.’ ”

Stearman was not ready to give up the battle, despite the Port Authority’s resistance.

“Clearly the New Jersey side does not want it over there,” he said. “I think everybody in Manhattan has to think, ‘Why in the world do we want to bring all those buses in?’ With transportation technology today, there seem to be a thousand reasons to have it across the river.”