BY DUSICA SUE MALESEVIC | Environmental groups are calling for General Electric to continue its cleanup of a dangerous pollutant that it dumped into the Hudson River.

“Time is running out on this issue because GE’s about to pull up stakes and move on,” said state Senator Brad Hoylman. “They’ve considered their job done. I think a lot of us believe differently.”

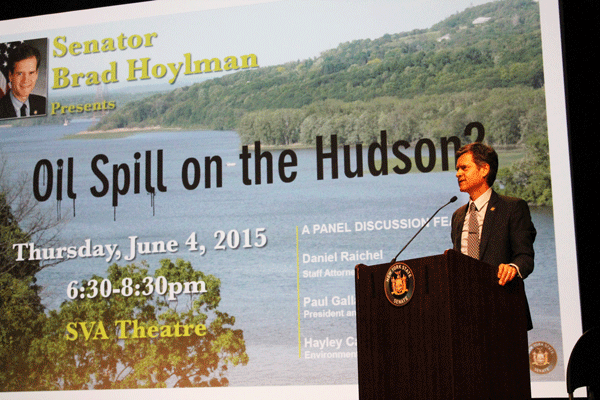

Hoylman’s remarks came at the start of a panel discussion about the future health of the Hudson River held Thurs., June 4 at the SVA Theatre, at 333 W. 23rd St. between Eighth and Ninth Aves.

PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, have plagued the Hudson for generations, said Daniel Raichel, staff attorney for the National Resources Defense Council.

Between the mid-1940s to the mid-’70s, Raichel explained, GE “dumped millions of pounds of PCBs directly into the Hudson River.” The manmade chemical was used in manufacturing because of its durability and is nonflammable even at high heats, he said.

GE discharged the PCBs into the river and they went everywhere, he said.

“Even though GE dumped PCBs into the river from plant sites way way north of Albany…the flow of the river, which goes both ways but mostly down, has brought PCBs to the entire New York area, including around Manhattan,” Raichel explained.

The actual amount of PCBs the company put into the Hudson is unclear, but some estimate as much as 1.3 million pounds. The majority is basically trapped in the 40-mile segment between GE’s plant sites and the federal dam in Troy, he said.

PCBs are easily absorbed into the human body and have been linked to cancer, as well as reproductive, neurological and hormonal disorders, Raichel noted.

The chemical has contaminated the river’s fish. It is recommended that women under age 50 and children under age 15 not eat fish from the Hudson, he said.

The 200-mile stretch of the Hudson River from Glens Falls, which is about 40 miles north of Albany, down to the Battery is a federal Superfund site because of the PCBs, Raichel said. It is one of the oldest and largest such designated contaminated sites in the country.

Under the Superfund law, called CERCLA (Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act), if you pollute a resource, you are responsible for cleaning up that resource, Raichel explained.

“CERCLA not only makes polluters clean up the resource, it also requires that they compensate the public for the damage done, and then restore the resource to its full health,” he said.

In terms of the affected areas of the Hudson, GE is financially responsible for everything, including damages, which have yet to be determined, he said.

In 2009, GE began a huge dredging operation to get rid of the PCBs in the upper Hudson. It’s an operation that takes hundreds of people, very sophisticated machinery and an expensive cleanup infrastructure, Raichel said.

Contaminated river sediment is dredged out of the upper Hudson and then taken to a hazardous waste plant. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency oversees the cleanup, and what has been done so far has gone well, according to Raichel.

“The clean up as planned by E.P.A. is scheduled to finish this summer,” he said. “The problem is that initially the E.P.A. only required GE to clean up 65 percent of the pollution in just the upper Hudson.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said that if the dredging work is stopped now, there could be the equivalent of a series of Superfund-caliber sites in the Hudson River, Raichel.

With GE planning to finish soon, it could then dismantle an estimated $200 million cleanup facility, he said.

“Once they break up and dismantle this facility,” the N.R.D.C. attorney said, “it may be generations before we have the opportunity to do the type of cleanup that we can do right now.”

GE can come to the table and negotiate with all federal actors “to make sure that all New Yorkers get the safe and usable river that they deserve,” he said. One of three things is going to happen, he said: GE is going to pay for it, the taxpayers can pay for it, or the PCBs are just going to sit there.

“I think it’s going to have to be intense public pressure and visibility of this issue,” Raichel said.

N.R.D.C., Scenic Hudson, Riverkeeper and others have organized a campaign for a cleaner Hudson. (More information and a petition are at cleanerhudson.org.)

“The next two months is crucial ’cause they’re well on their way to completing their final year of currently mandated dredging,” said Paul Gallay, president of Riverkeeper.

Hoylman said he is circulating a letter among his state Senate colleagues — addressed to Governor Andrew Cuomo and GE C.E.O. Jeffrey Immelt — “to put pressure on them to revisit the dredging and make certain that they don’t leave before the job is finished.”

GE declined to comment for this article.

PCBs are not the only threat to the Hudson’s health. Hayley Carlock, environmental attorney for Scenic Hudson, explained that every week there are 25 to 35 trains carrying crude oil along the banks of the Hudson.

Around three years ago, Bakken crude was discovered in North Dakota and production skyrocketed. The amount of crude oil shipped by rail in the U.S. has increased 4,000 percent since 2012, said Carlock, “and that’s why the risk has risen so greatly.”

Bakken crude is unrefined petroleum that is very flammable, she explained.

Much of it — over one-third of the Bakken crude — goes down the Hudson River from Albany to New York City, and is destined for refineries in New Jersey and Philadelphia.

A derailment of a train loaded with Bakken crude could lead to devastating explosions and fires, Carlock said. If the Bakken crude were spilled into the Hudson, the best-case scenario would be that only 20 to 25 percent of the oil could be recovered, she said.

The Hudson Valley is “the last place that something like this should be shipped,” Carlock warned.

“We all have to be concerned with that,” Hoylman concurred.