Police radios in four more Brooklyn precincts went dark on the morning of Sept. 11, as the NYPD seemingly took another step in its controversial plan to encrypt all communications from the public.

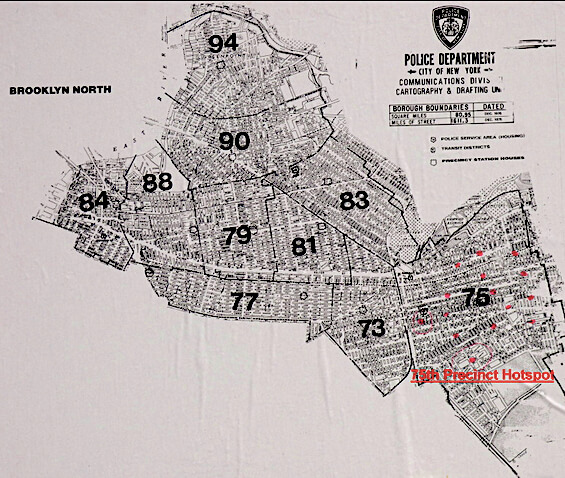

The effort began in July with four northern Brooklyn precincts going dark. The latest round of encryption enacted Monday, the 22nd anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, included the 75th Precinct in East New York, Brooklyn, referred to by some as New York’s “Killing Ground” for having high crime and murder rates; the 77th and 79th Precincts, which encompass Crown Heights and Bedford Stuyvesant; and the 73rd Precinct that include Brownsville, East Flatbush and East New York.

The NYPD shut down police radios using encryption, a radio technique that makes it impossible for scanner radios and scanner apps to listen to radio transmissions. Critics have called radio encryption “the most regressive transparency issue in the history of the state.”

Public Advocate Jumanne Williams, a frequent critic of the department, in the past called the radio silence, “terrible.”

“This is a troubling trend, and the antithesis of the transparency that we need in law enforcement,” Williams said. “I’ve heard no rationale for why the press or the public should have their access to these airwaves suddenly restricted – public safety requires public accountability.”

The NYPD has maintained that encryption is a security and safety issue, preventing criminals from monitoring police transmissions. It also prevents outsiders with radios from interfering with police communications as has occurred in the past during Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

Most radio interference, however, has occurred when officers lost radios in the field; with the new radios, the NYPD can remotely shut the radios down and make them useless.

The use of encryption has been spreading throughout the country, ever since the federal government complained that police should maintain privacy of victims in the field. That however, has prompted most police agencies to use department issued phones to relate personal details of crime victims to their headquarters without sharing with the public.

The NYPD issued a statement on the encryption Monday afternoon: “The safety of our first responders and the community will always remain the NYPD’s top priority. The Department works day-in and day-out to be transparent and build trust with the public. We are continuing to explore whether certain media access can be facilitated, including utilizing methods that are already being used in jurisdictions with encrypted radios.”

While crime has dropped in most of the city this year, the areas where police radios were encrypted Monday represent some of the highest numbers of homicides, shootings, robberies and other violent crimes in the city.

Community groups that have been working with the police have been using the Citizen App, a phone App that tells residents of the community about crime and other incidents in their area. More than two million people in New York City alone use the Citizen App. Officials from Citizen have in the past expressed confidence that the city will provide some sort of access so they may confirm calls and tips and then notify users of incidents in their community. Citizen officials had no comment as yet.

Members of the God Squad, a grass-roots violence interruption group, have been using Citizen App to mediate disputes and calm situations. Other groups including the Flatbush Village, use police radio transmissions to be able to respond to trouble spots and tamp down violence.

Recently, Deputy Inspector Eric Robertson from the NYPD Deputy Commissioner of Public Information office said the department will provide access, most likely a delayed transmission. He had expressed frustration that they could not trust some members of the media to listen to real-time transmissions since they no longer vet press credentials.

“We can’t trust the police to sit down and talk to us when they said they would. It’s just a shame,” said Bruce Cotler, president of the New York Press Photographers Association. “They are promising to sit and talk and then go behind our backs and encrypt four more frequencies. Those are the two precincts I listen to the most (the 73 and 75). Years ago, a cop told me, ‘if doesn’t happen in the 75, the guy who did it lives there.’ They are taking away our ability to inform the public, good or bad.”

Recently, a group of press organizations called the New York Media Consortium spoke with representatives of the City Council about holding a public hearing about the encryption issue. Other media organizations have also implored the City Council to hold a hearing to address the transparency issue. No hearing is yet scheduled.

Many important stories were uncovered due to members of the media being able to monitor radios including the choke hold death of Eric Garner in Staten Island for selling individual cigarettes, the shooting death of Sean Bell on the night before his wedding and the death of Amadou Diallo after he was shot by police after holding up his wallet for ID.

Police radio broadcasts also alerted the media of the attack on the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001, and their warnings regarding the severity of the attack helped save many lives.

Elected officials have thus far been non-committal on the issue, though Council Speaker Adrienne Adams said in an interview with ABC-Eyewitness News that she would hold a hearing on the matter. No date has yet been set for this hearing, though it is still being considered.

Officials in her office referred to her statement on July 28 in which she said in part, “Transparency is key to achieving and maintaining public safety. It is troubling that the NYPD began encrypting its radio system without an adequate transparency plan implemented first, which can jeopardize the safety of New Yorkers.”

Read more: Behind Joey Ramone’s Famous Hairstyle