BY BILL WEINBERG | Received in the mail this week, from the wilds of New Hampshire — a historical and cultural offering from a member of the East Village diaspora, dispersed from its urban homeland by the forces of gentrification. To wit, Carl Hultberg, my E. Fourth St. neighbor and buddy of many years, now a cabin-hermit in the Great North Woods.

The five-volume set of monographs is collectively entitled “Garden of Eden: The Eco Eighties in New York City,” and mostly consists of Carl’s photography from the era, with a big emphasis on the Village and Lower East Side. It is published under the imprint of Ragtime Society Press. (An aside: Carl is the grandson of Rudi Blesh, the famous jazz critic and promoter, and among his other projects was the Rudi Blesh Ragtime Society music appreciation club. His cavernous antebellum apartment that he inherited from Rudi was packed almost to capacity with vinyl — an international collection spanning ragtime, jazz, blues, rock and way beyond.)

The ’80s are remembered more for Reagan reaction and Koch conservatism than radical ecological politics. But they were a time when, below the surface, the consciousness shift that began with the counterculture upheaval of the ’60s and continued through the environmental movement of the ’70s was ripening, getting serious about manifesting its vision in concrete alternatives.

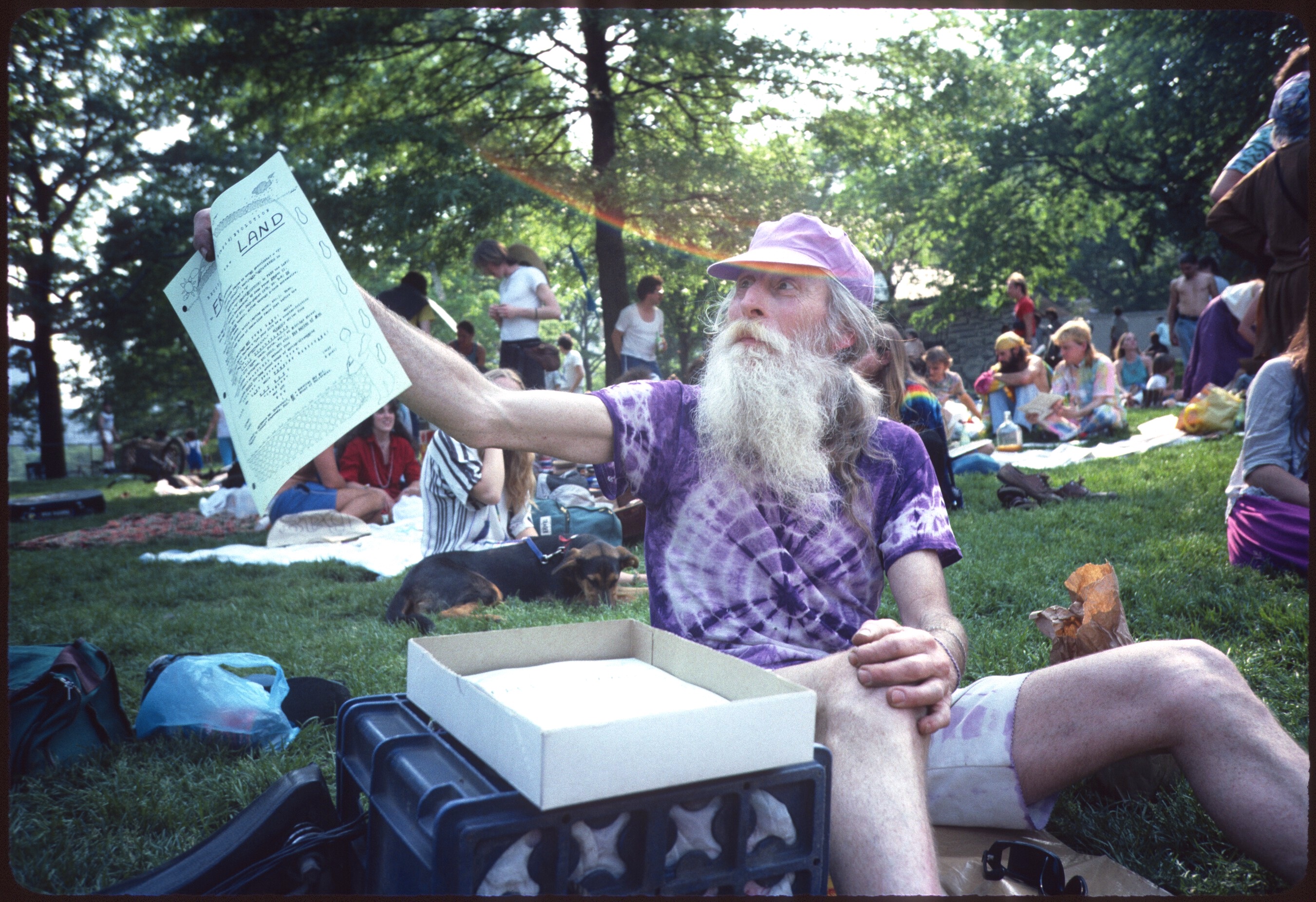

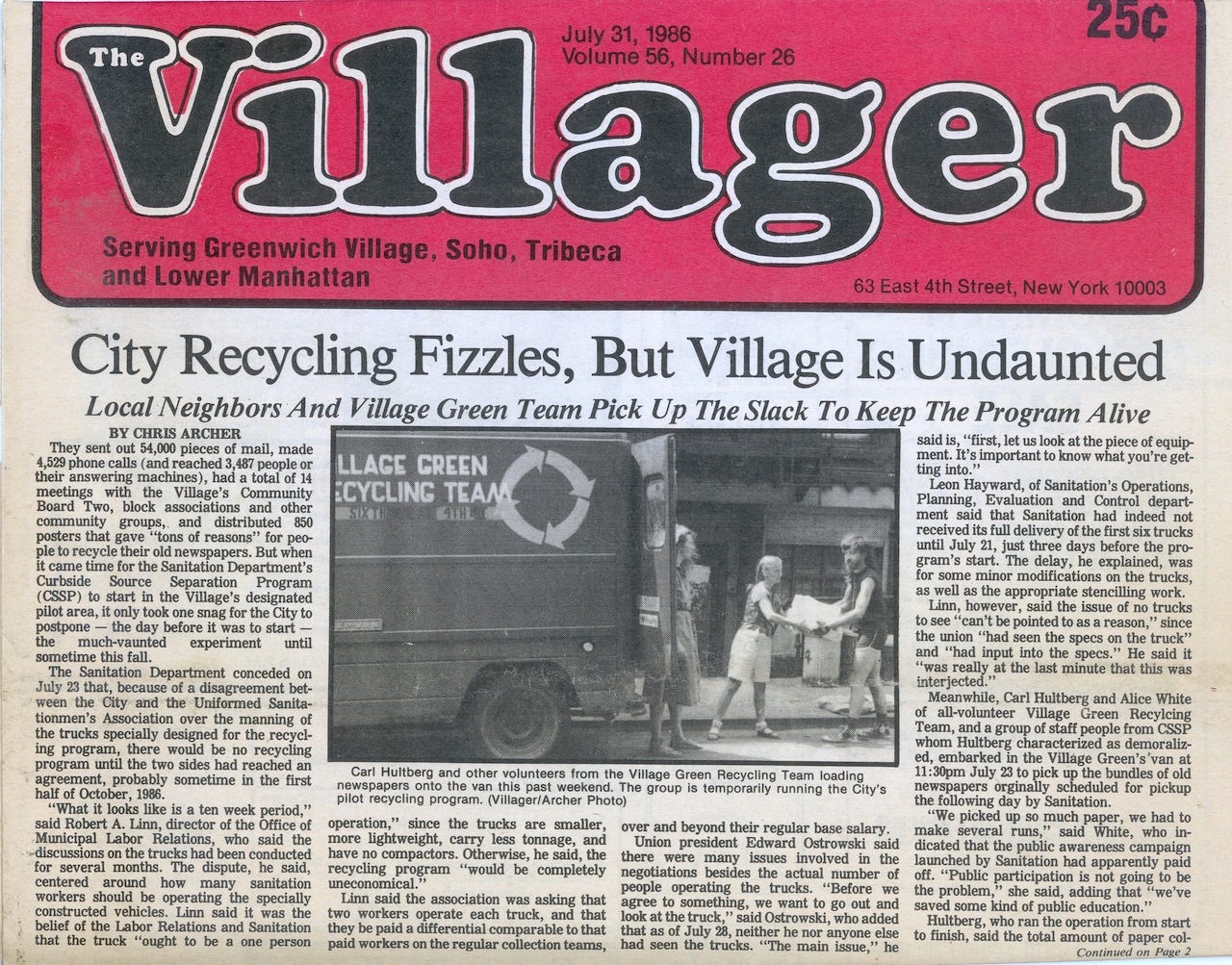

Carl’s special project in those years was the Village Green Recycling Team, one of the first efforts at a recycling program in the city. He was also involved in the New York Greens, a nascent attempt at a Green Party in the city. This effort ultimately came to little, but it did bring together various activist and ecological projects from around the metro area, immersing Carl in an alternative culture that would prove an incubator for ideas later adopted by the mainstream.

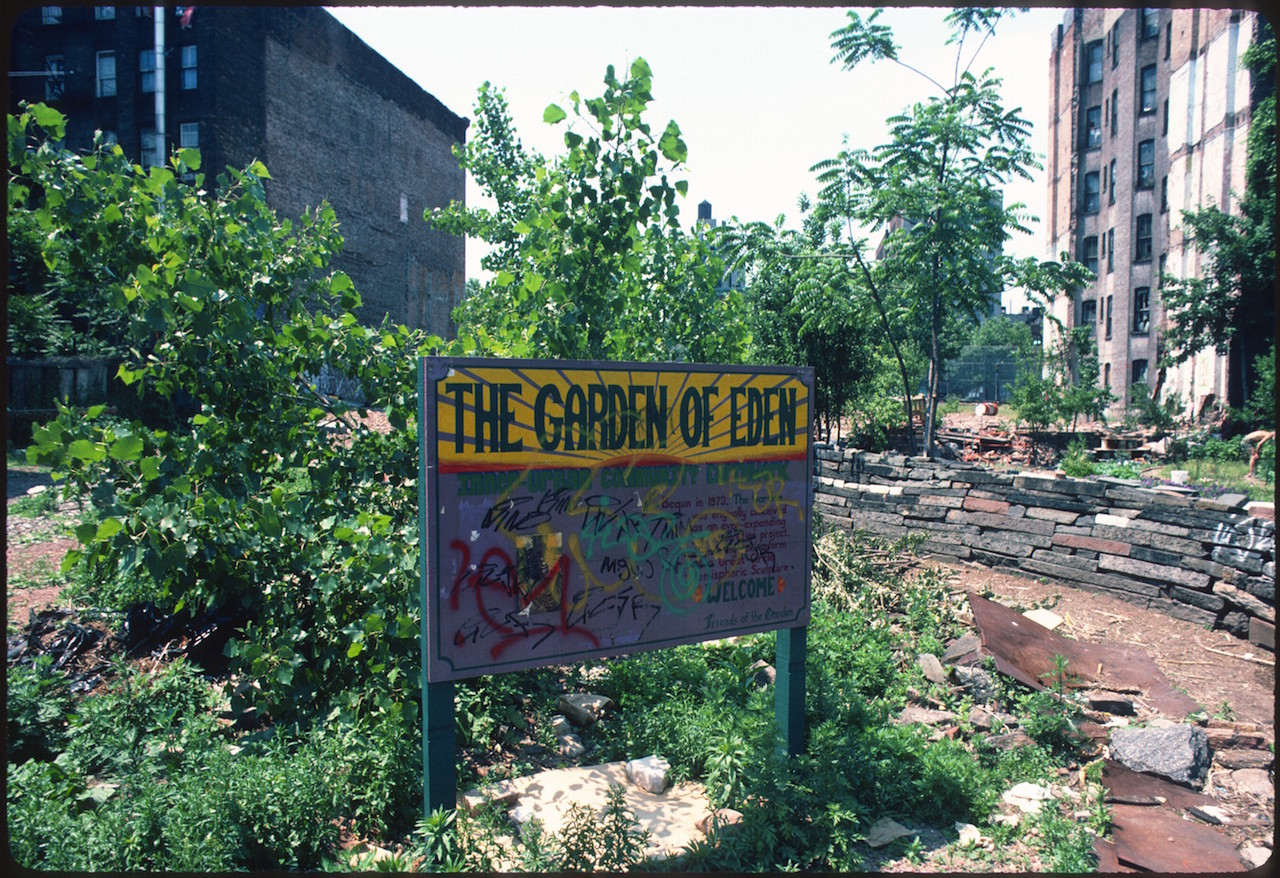

The first volume is devoted to the New York Greens and related activist efforts; the next two to the late Adam Purple’s Garden of Eden and community gardens; the fourth to experiments in bicycle and human-powered vehicle (H.P.V.) design; the last to urban cycling and recycling. Shots of the celebratory All-Species Parade, with art-activists dressed up in homespun costumes to impersonate their favorite endangered animals, contrast those of scruffy volunteers pushing handcarts piled high with newspapers.

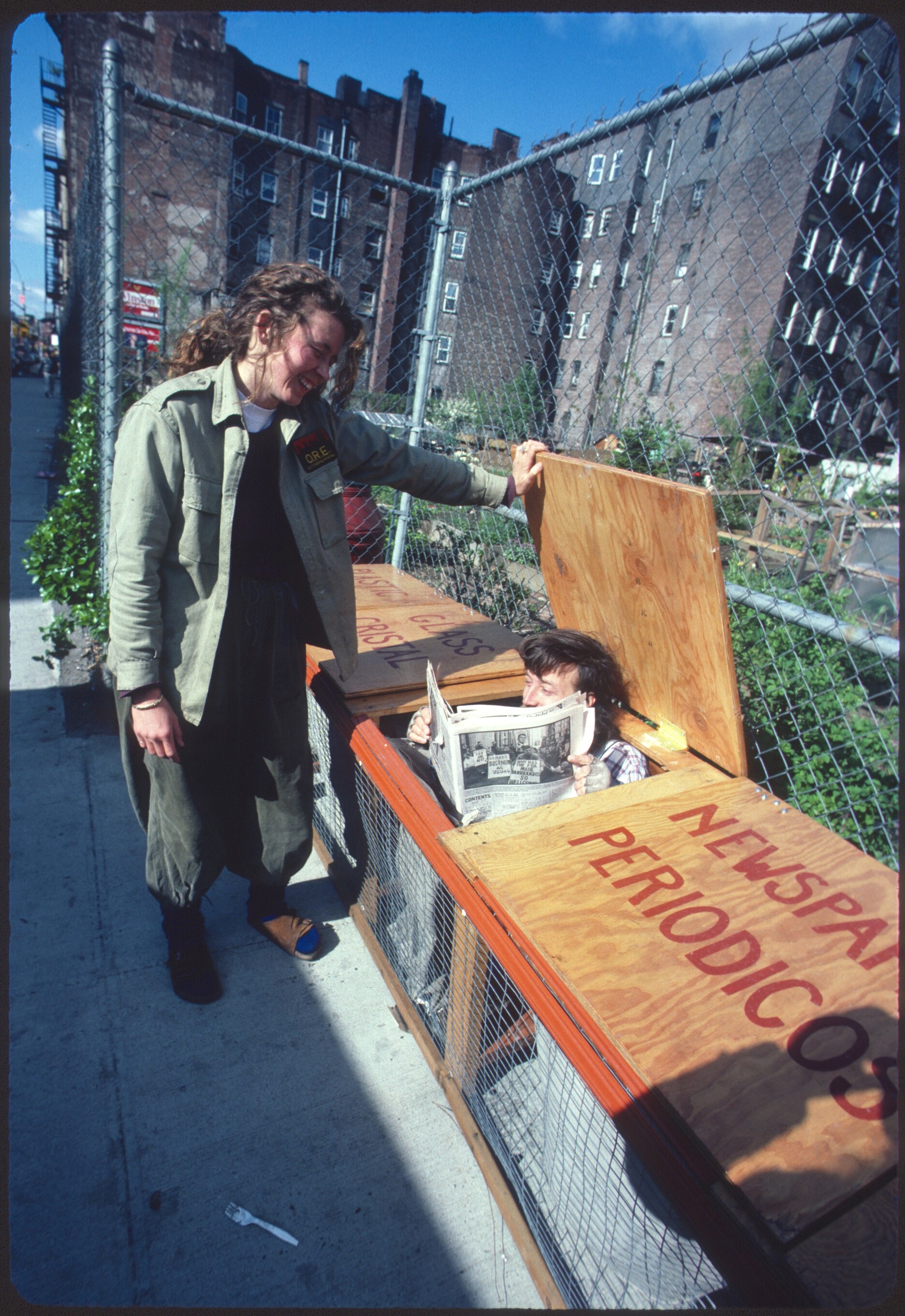

The Village Green Recycling Team and sibling Lower East Side Ecology Center, by their very existence, put pressure on the city to launch an official recycling program. Environmental groups were lobbying the City Council to pass a bill mandating such a program, after much resistance from the Sanitation Department. The enviros could point to these grassroots initiatives as evidence that recycling could work in the megalopolis; the bill was finally passed in 1989.

Among the images reproduced in “Garden of Eden” are Villager articles on these efforts from back in the day. (The L.E.S. Ecology Center continues to serve as a compost drop-off site today; hopefully, the bureaucracy will again follow the grassroots pioneers and instate a mandatory citywide composting program in the coming years.)

Although I couldn’t find a photo of it in his monographs, Carl’s apartment for years sported a sign in the window reading: “COOPER UNION, HOW COULD YOU DO THIS TO OUR NEIGHBORHOOD?” Another, actually illuminated from behind, read, “LIFESTYLES OF THE SICK AND SHAMELESS.” This was a reference to the Bowery Bar (today the B-Bar), which opened on the block, an early toehold of gentrification, in a reconverted gas station that had been long abandoned. The Cooper Union arts and engineering school owned the site, and Carl’s friend (and sometime housemate) George Bliss sought to establish an H.P.V. workshop there. Instead, Cooper Union turned the property over to developer Eric Goode, who transformed it into the B-Bar. In its heyday, when it drew the glitterati (it has since become déclassé), the signage right next door registered silent protest with those waiting on line to get in.

Bliss opened his workshop elsewhere, producing and marketing pedicabs and the big truck-trikes used by the V.G.R.T. This workshop, known as The Hub, bounced around to a few locations — most recently in the West Village, where he sold and rented alternative-model bicycles. It finally closed its doors in 2014 — according to George, forced out of business by the advent of Citi Bikes.

Also documented is the struggle of bicycle messengers to keep Fifth, Park and Madison Aves. open to bikes after the Koch administration issued an order banning them from those Midtown thoroughfares during working hours in 1988. This was the first time the messengers really got organized, in what Carl calls “a spontaneous American labor movement.” They repeatedly rode en masse in defiance of authorities, and ultimately prevailed in getting the ban overturned. These actions presaged the Critical Mass bike rides that took off in the ’90s, cyclists making the point with their bodies to demand their right to the road.

Again, this demand would later be taken up by the bureaucracy under Mayor Bloomberg, and dedicated bike lanes began appearing on many Manhattan streets — with stretches of Broadway now closed to cars entirely.

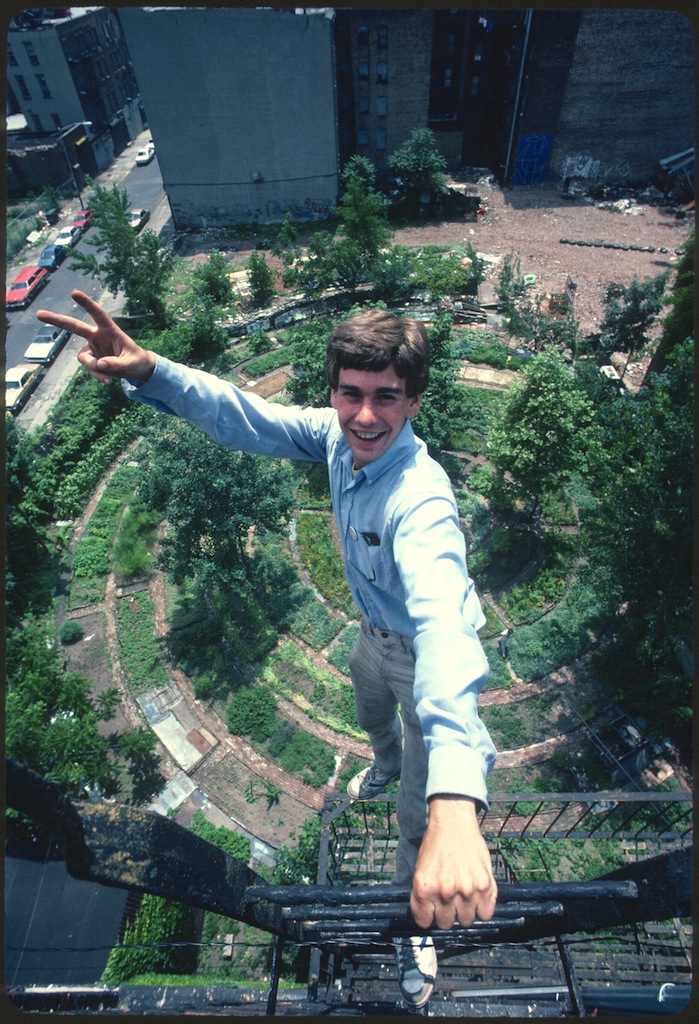

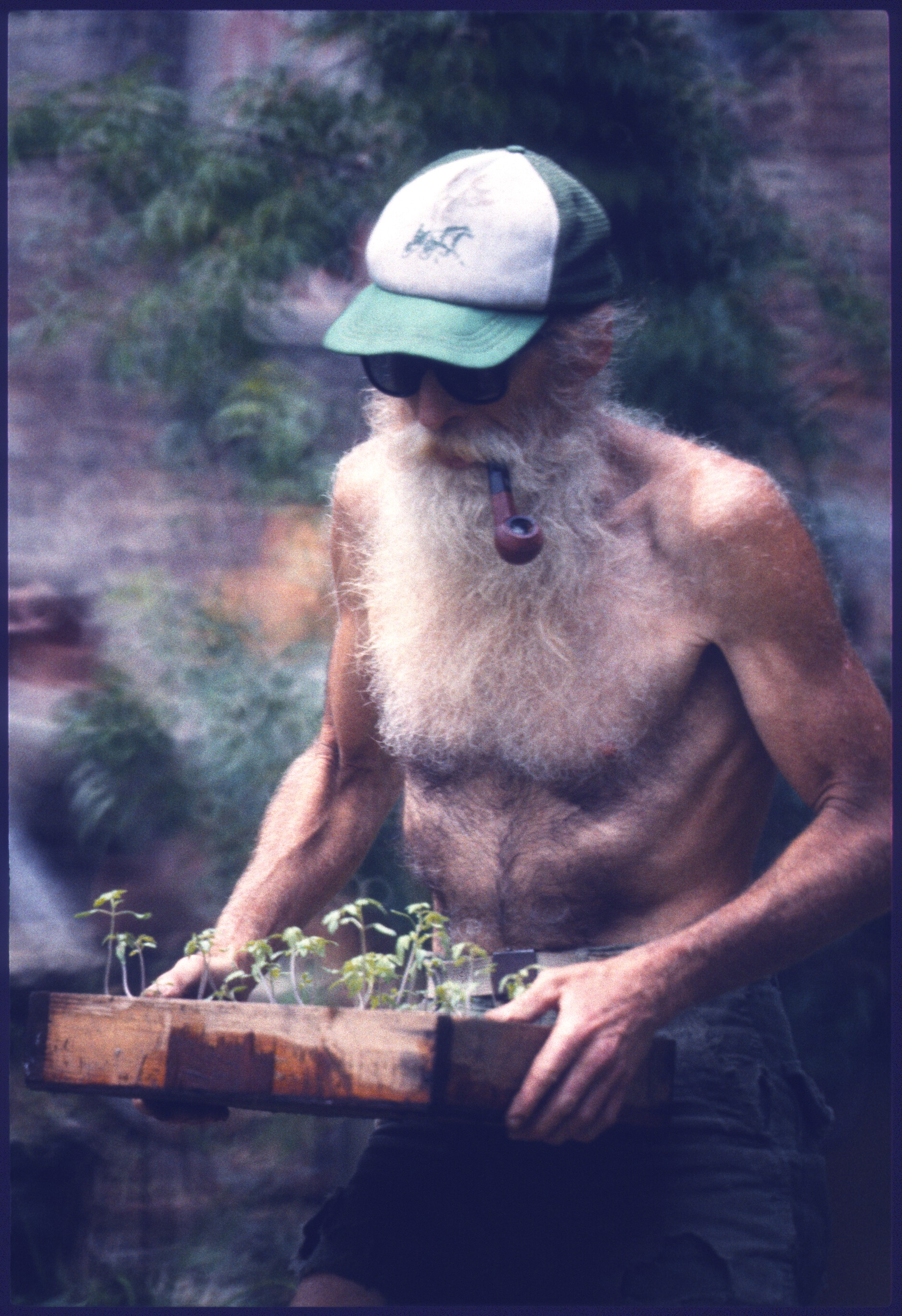

Then there’s Adam Purple. The two volumes devoted to him contain shots of his garden before, during and after its destruction in January 1986. (Particularly poignant images show Adam’s cat, forlorn in the post-destruction rubble.) The destruction of Adam’s garden both set a dangerous precedent that gardens could be destroyed by city government fiat and galvanized a movement to defend them — ultimately resulting in the deals that saved hundreds of gardens around the city in the early years of the Bloomberg administration.

Of course, it’s a bitter irony that gardens, bike lanes and pedestrian malls are today seen by many as greasing the way for further gentrification (in the case of the pedestrian malls, actual privatization of public space). As the bureaucracy embraces alternative models, it has the effect of destroying those very grassroots initiatives that broke ground for them and made them possible. The most blatant example is Citi Bike, a program that bears the name and logo of a financial behemoth — representing corporate recuperation of progressive, even radical ideas.

Carl’s “Garden of Eden” commits to our collective memory those radical origins — and the lesson that all progress, ultimately, comes from below.

Carl Hultberg’s “Garden of Eden: The Eco Eighties in New York City” is available for purchase on Amazon.