Fleeing from drug cartels in his native Colombia, Jonathan Ochoa is just one of the thousands of migrants who have endured long journeys to New York to start a new life in America.

The path toward financial independence that only employment can provide is only available to migrants who secure work visas. But obtaining the important government documents too often turns out to be a bureaucratic nightmare.

Ochoa and his wife have not yet applied for work permits, saying that they have been overwhelmed by a process where the applications themselves are complex and only available in English.

Many of the migrants who have come to New York are in a similar boat, faced with a bevy of hurdles, making it difficult to file for asylum, work permits and other forms of legal status. The roadblocks have made it difficult for them to gain financial independence and be free of city shelters.

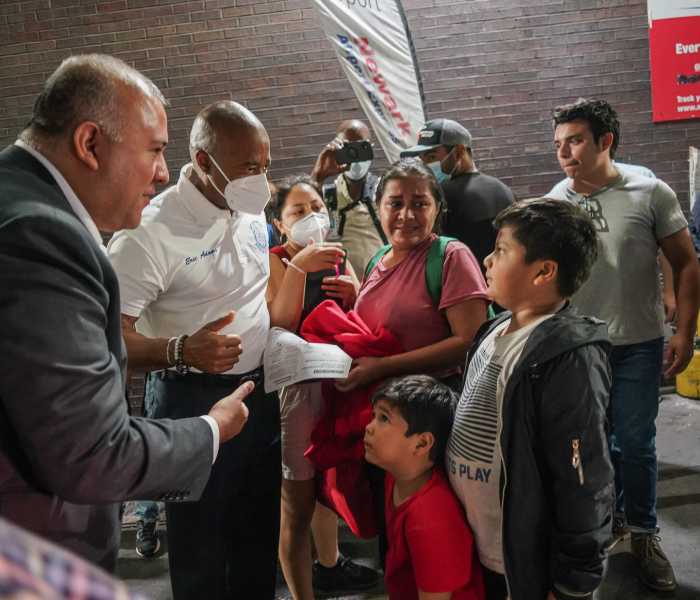

While Mayor Eric Adams’ administration has taken steps to assist newcomers like Ochoa in navigating the bureaucracy, only a small number of migrants have submitted claims for asylum and work authorization at this point.

Fighting for legal status

Ochoa, who does not speak English and spoke to amNewYork Metro through a translator, filed for asylum several months after arriving in New York, completing the complicated and cumbersome application without any legal assistance.

Asylum is a status that allows foreign nationals who can prove they have been persecuted or fear persecution in their home country to live in the U.S. Migrants only have a year to apply for asylum, then the window is closed.

Once migrants apply for asylum, they can live in the U.S. legally until their case goes before an immigration judge and a decision is rendered, which often takes many years.

Those who file for asylum can then apply for a work permit 150 days after filing a claim. They then must wait an estimated 30 days to be granted legal work authorization.

A migrant’s current legal status in large part depends on how the individual entered the country. According to immigration lawyer Stephen Yale-Loehr, there are several ways that new arrivals typically enter the U.S.

Some migrants arrive at official ports of entry, like Ochoa did, and tell authorities that they plan to file for asylum, which they do some time later. They are then released at the border with an immigration court hearing date. Many of those migrants are also granted parole, a status that allows them to seek employment when they file for asylum.

Parole, in terms of immigration, is a legal status that “allows temporary harborage in this country for humane considerations or for reasons rooted in public interest,” according to Yale-Loehr. It can be granted for a number of reasons, such as preventing the separation of families.

Others enter between ports of entry, Yale-Loehr said, and are caught by immigration authorities. These newcomers can also claim asylum and are often released on parole.

But there are also migrants who, after getting arrested and released, are not given parole and are just told to apply for asylum, Yale-Loehr said.

The main difference is that migrants granted parole are able to immediately apply for a work permit, he said, whereas those without the designation cannot. Those with parole, for instance, do not have to wait 150 days before filing for work authorization.

“It seems to be hit or miss as to who gets parole versus being told just to file an asylum application,” Yale-Loehr said.

A third group is comprised of migrants who come across the border between designated entry points and avoid arrest. Yale-Loehr said they don’t have status and remain in the country undocumented.

Then there are individuals who come on temporary visas, such as tourist visas, who overstay.

And finally, there are migrants from countries covered by Temporary Protected Status (TPS), a designation offered to people from certain nations the U.S. has deemed too dangerous for the migrants to return.

TPS provides immigrants with protection from deportation and provides them with the ability to apply for legal work authorization. However, the status only applies to those who are already in the country when it is enacted and it does not help new people immigrate to the U.S.

Ochoa and his family were unable to apply for TPS, as they are not in one of the groups currently eligible. Instead, they filed for asylum, although have yet to file for work authorization.

In September, President Joe Biden extended and redesignated TPS for Venezuelans who arrived in the country before July 31, which covers roughly 15,000 Venezuelans in New York City, according to the Adams administration.

Enormous legal challenges

Yale-Loehr said migrants are confronted with a slew of legal obstacles when trying to avoid deportation and build a life in the U.S.

“There are so many challenges they have,” Yale-Loehr said. “Just on the legal front, understanding the work permit complexities, depending on what status they are. Trying to find an immigration lawyer or other advocate who can help them navigate this process.”

The city has stepped up its efforts in recent months to assist migrants in applying for asylum and work permits.

The push began with the opening of an “Asylum Seeker Application Help Center” in June, which is staffed by “application assistants” who help migrants complete their required forms under the supervision of pro-bono immigration attorneys. The center is run by the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (MOIA).

Ochoa, however, was not one of the migrants helped by the center. He said that when he tried to make appointments, he was told “‘you have to wait … or you have to call back in a week.’” He added it turned into a cycle of calling and being told to call back.

The only time Ochoa was ever able to reach a pro-bono attorney through the phone numbers provided by the city and state, he said the lawyer told him they would not be able to help with his asylum case.

Additionally, Ochoa said he has generally had trouble with accessing the legal services offered by the city and state because the advisors who answer the phones mostly speak English, making it difficult for him to ask questions.

“The government says there’s a lot of aid but all the lawyers giving us information … [like resource phone] numbers, they’re [unreliable] numbers,” he said through a translator. “You call and they never answer and when they do answer, so you don’t ask any questions, they speak to you in English.”

When asked about the experiences of Ochoa and other migrants like him, Mayoral spokesperson Kayla Mamelak-Altus said that the application help center marks an “unprecedented effort” to help migrants apply for asylum, work permits and TPS in one location. However, she said that due to the “huge volume” of individuals the center is serving, more help is needed from the federal government.

“With the responsibility of caring for over 65,300 asylum seekers right now, and hundreds more arriving every day, New Yorkers continue to look to the federal government for financial support, partnership in processing applications more quickly, and a national decompression strategy to address this national crisis,” she said.

She added the city reached out to families with children in its care three times when the center first opened to offer them appointments and that there is ongoing outreach at emergency shelters.

City Hall says the application help center has so far assisted migrants in submitting 6,453 asylum claims, as of Friday, Nov. 3.

Although anyone can apply for asylum, it is very difficult to actually be granted the status, Yale-Loehr said. Nationally, less than 50% of those who submit claims are granted asylum, he said, and the chances are even lower for those who are not represented by an immigration lawyer.

In New York City between fiscal years 2017 and 2022, 35.25% of asylum claims were approved, according to data from Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC).

Work permit assistance

When it comes to getting more migrants legal work status, the administration says it has helped file 1,024 applications for work permits as of Friday, Nov. 3. It has also helped file 795 TPS applications.

On top of that, the city, state and federal governments came together with immigration advocates to set up a two-week clinic in Lower Manhattan early last month that helped migrants submit employment authorization applications. The clinic assisted newcomers in filing an additional 1,700 work permit applications, according to City Hall — bringing the total number thus far to over 2,700.

While the number of applications filed by the clinic is impressive, Yale-Loehr said, the city needs to be more consistent in its efforts to help migrants put in for work permits. Furthermore, it needs to step up its outreach so a greater number of newcomers are aware of them.

“We need to have more money, and train more paralegals and more lawyers to be able to do this on an ongoing basis,” Yale-Loehr said. “Because 2,000 is great, but there are over 100,000 recent migrants who have come to New York City.”

Mamelak-Altus said the city is in talks with the feds about bringing back the clinic for a longer period of time in the future.

A long, perilous journey

Ochoa is one of roughly 130,000 migrants who have come to the Big Apple since April 2022, with most from Latin America and West Africa. He is also one of over 65,000 newcomers living in city-run shelters — in his family’s case a converted Holiday Inn Express in the Gowanus section of Brooklyn.

Ochoa, his wife, son and daughter began their journey by flying from Bogota, Colombia, to Mexico City. From there, he and his family ventured through the Mexican desert to the U.S. border, he said.

Both 35 years of age, the Ochoas paid smugglers for transportation and protection to cross the border, since they brought with them their daughter, 14, and son, 8, whom they wanted to keep safe, he said.

“We paid a person in Mexico City to connect us with … a specific person to help transport us in [a] car, in protected buses, until we reached the border,” Ochoa said.

The smugglers — known as coyotes — also put them up in safe-houses along the way. But he said that even with the coyotes’ protection they were in “constant fear” because there were often armed people nearby who were not part of their group.

Ochoa said they eventually crossed the U.S. border at an official port of entry in Arizona and were arrested by American border agents, who separated he and his son from his wife and daughter.

Ochoa and his son were brought into a processing center he referred to as “the fridge” — because it was very cold and bright — where they were held for three days.

After the processing was finished, Ochoa’s family were reunited and were granted parole.

Immigration authorities gave them one hour to book a flight to a city of their choosing or face deportation, Ochoa said.

They decided on New York.

Life in NYC, under-the-table work

Since arriving in the five boroughs on Aug. 28, 2022, Ochoa’s family has been living in city-funded shelters and working under-the-table jobs to support themselves.

Similar to Ochoa, many recent arrivals have come to New York fleeing deteriorating conditions in their home country, such as political unrest, violence and economic instability.

Despite the city’s recent efforts, Ochoa said he and his wife have not been able to file for working papers due to the complexity of the application process and many of the materials only being available in English. Instead, they, like many other recent arrivals, have resorted to taking below-minimum wage jobs off-the-books to support themselves.

Ochoa expressed doubt about how successful the city has been in assisting migrants with applying for asylum and employment authorization because of the issues he has encountered with the system.

“The aid they’re trying to convey now is a lie,” he said, “or they tell you to fill out paperwork and they don’t call you back.”

Camille Botello contributed to this story as a reporter/translator.